Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Dreadful Ways The Victorians Accidentally Poisoned Themselves

The Victorians were a clever lot. They gave us steam trains, stamps, photographs, and the first public flushing toilet. But they were also rather accident-prone. A bit like letting a child play with matches in a firework factory, the Victorians had a lot of dangerous chemicals at their fingertips. In the days before health and safety, their idea of protection was to print a skull and crossbones on a bottle of arsenic. The flaw with this plan was that they then happily sold the same arsenic over the counter as rat bait, often with dire consequences.

Let’s take a look at a world where appearances were everything and safety came second. It was the 19th century, and the Victorians found some pretty weird ways of accidentally doing away with themselves.

10 Wallpaper

Rather than 50 Shades of Gray, the Victorians were passionate about the color green. In fact, green wallpaper was to the home what an iPad Air is to tablets. This love of green came about because of the end of the window tax and gas lamps. With natural light flooding in during the day and better light at night, the Victorians unleashed their inner passion for bright colors.

The fashionable color to dress the walls with wasn’t just any green. It had to be a lush shade called Scheele’s Green. Not only was it bright, but it resisted fading—an extra boon. The dark side of this colorful wall dressing was that it slowly poisoned people. Copper arsenite, an arsenic derivative, gave it the rich color.[1] Breathing air polluted with arsenic vapor had the potential to kill . . . and often did.

Whole families ailed and died, with children especially at risk. The signs of arsenic poisoning were similar to diphtheria, so many politicians remained skeptical of the danger. And those doctors who did voice concern about arsenic were often publicly ridiculed, especially by companies producing the wallpaper!

It took until 1903 for arsenic compounds to be forbidden as a food additive, but the use of arsenic in wallpaper was never formally banned.

9 Baby Bottles

Roman mothers used hollow horns to feed their babies, and baby bottles were nothing new in Victorian times.[2] What was new was a special glass bottle fitted with rubber tubing and a teat. The idea was the infant sucked on the rubber tube, like sucking cola through a straw.

These bottles were backed by a popular marketing campaign and given names such as “The Little Cherub” or “The Princess.” Mothers loved how an infant could feed themselves; it was a source of great pride. These feeding bottles became the go-to accessory for the modern Victorian mother—but with deadly consequences.

There was a basic design flaw: The rubber tubing was set into the glass and nearly impossible to clean. Inside the bottle, warm milk made it the perfect breeding ground for bacteria. The advice given by Mrs. Beeton, the household guru of the day, didn’t help. Writing in 1861, she declared it wasn’t necessary to wash the bottles for two to three weeks.

The result was babies drinking a soup of bacteria, often with fatal consequences. Indeed, the bottles soon gained another name: “murder bottles.” This, along with the condemnation of doctors, should have stopped their use. But it didn’t. Sadly, many mothers were taken in by advertising and continued using them regardless.

8 Carbolic Acid

The Victorians just couldn’t get the balance right. Take hygiene, for example. On the one hand, they used dirty baby bottles, and on the other, they came up with the saying, “Cleanliness is next to Godliness.” Top this off with new theories about germs causing infection, and the urge to clean became obsessive. So they poisoned themselves with carbolic acid.

Every household had caustic soda or carbolic acid, used as cleaners, in a cupboard somewhere. But therein lay the problem. These deadly products came in packaging that was identical to other household items, including foods.[3]

It was easy to confuse one box with another and accidentally poison the cakes. In September 1888, this is exactly what happened when carbolic acid was mistaken for baking soda. Thirteen people became sick, and five died.

It was another 14 years before the Pharmacy Act made it illegal for chemicals to be stored in similar bottles to ordinary items.

7 Lead

It’s almost as if the Victorians wanted to die!

With the Industrial Revolution, cities started to expand. This meant supplying households with water. Reservoirs were built to supply standpipes in the poorer districts or houses in affluent areas.

However, much of that water traveled along lead piping, picking up the deadly toxin as it went. Interestingly, it is from the Latin word for lead, plumbum, that we derive the term “plumbing.” What makes this all the more ironic is that in 1847 and 1848, the British government wrote laws making it a criminal offense to pollute drinking water.

But the danger didn’t end with water. Lead was added to paint to stop it from flaking and to make the colors vivid. The Victorians slathered lead paint over furniture, cots, and even children’s toys. When children gnawed on their cribs or chewed on toys, they accidentally poisoned themselves.[4]

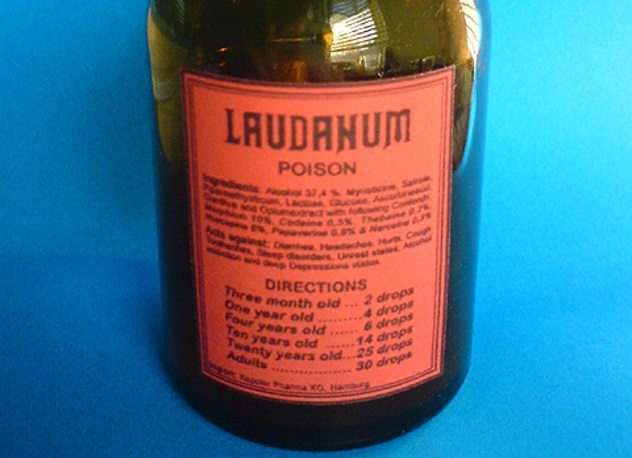

6 Laudanum

Laudanum was the Victorian equivalent of aspirin. It was a cure-all that settled nerves, eased pain, and ensured restful sleep. The only problem was that laudanum is a syrup of opium.

Laudanum was available from any pharmacy to buy, and it was affordable at around 25 drops for one penny.[5] While the wealthy looked down on the poor as laudanum addicts, they failed to see their own dependence and merrily imbibed this addictive cordial. Laudanum was widely marketed to women to ease their ailments, such as menstrual cramps and “hysteria.” Ironically, it’s possible laudanum that was taken by women to ease the symptoms of arsenic poisoning by their green wallpaper!

Of course, opium is addictive. This meant people became dependent on the feelings of euphoria it created and took more and more. The alternative was to withdraw, with the typical symptoms of tremors, hallucinations, and sweats. With the doses unregulated and laudanum freely available, overdose was common.

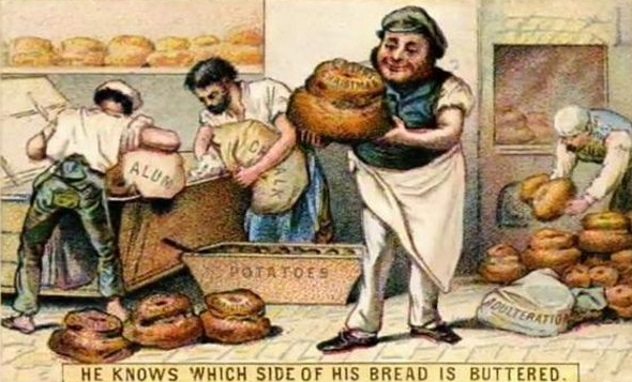

5 Adulterated Bread

The Victorians judged by appearance. They tended to link white to purity, and whiter meant better. They had an obsession with white bread. With all the nasty wheat germ and bran taken out, they looked on white bread as pure and healthy. By some twisted logic, adding a chemical whitener—alum—made it even better.

Compounds referred to as alum are double sulfate salts of metals like aluminum or chromium. Traditionally, alum was used in the medieval wool trade to fix dyes and was later used in styptic pencils. It doesn’t even sound like it would be healthy.

Sadly, alum has no nutritional value. The addition of alum robbed the poor, for whom bread was a staple of goodness, and led to malnutrition. Indeed, it contributed to a range of deficiency-related diseases. Worse even than that, alum irritates the bowel wall and can cause long-term stomach upsets or constipation. For small children, this was a step too far and caused deaths.[6]

4 Boracic Acid In Milk

Boracic acid belongs to a family of mild acids which include borax and boric acid. They are mostly used today in insecticides. Doesn’t make it sound a great addition to milk, does it? However, here we find home guru Mrs. Beeton raising her hand again.[7]

In the days before pasteurization and fridges, milk could contain harmful bacteria and go bad quickly. To prevent this, Mrs. Beeton advised the addition of boracic acid to milk as a preservative. It also had the benefit of sweetening the flavor slightly and removing any sour, tainted taste.

The effects of boracic acid on adults are usually mild, such as nausea, stomach cramps and diarrhea. However, the chemical hid the taste of turned milk, meaning many people drank what wasn’t fit for consumption—with upsetting consequences. For children, too much boracic acid can cause seizures, neurological problems, and even death—in the very group most in need of the health-giving benefits of milk.

3 ‘Corpse’ Candles

At the beginning of the 19th century, candles were either made from tallow or beeswax. The former burned with a sooty flame and smelled bad, while the latter were expensive. But a new process formulated in 1810 changed this.

A French scientist, Michel Chevreul, hit on a way of separating tallow and adding a secret ingredient which made for cheap, high-quality candles. Although banned in his native France, these candles took off big-time in England. The craze for these compound candles peaked in 1835 and 1836.[8]

However, one night, a professor of chemistry was working late by the light of his new candle. He smelled a garlic odor coming from the melted wax and became suspicious. He knew arsenic compounds had a garlic-like smell and correctly identified the secret ingredient as arsenic. Professor Everitt ran tests, confirmed his suspicion, and made his deadly findings public. Writing in The Lancet, he described these new products as “corpse candles” because of their deadly vapor.

2 Gas Lighting

After candlelight, one can only imagine how magical gas lighting must have appeared in the 19th century. However, it was not without considerable risks. The Victorians used mostly coal gas for their gaslights, which was a cocktail of hydrogen, sulfur, methane, and carbon monoxide.

This mix was a deadly, with hazards including suffocation and carbon monoxide poisoning, plus the risk of explosion. Indeed, the image of a wilting Victorian lady suffering a fit of the vapors may be due in part to a slow leak of carbon monoxide into a sitting room, coupled with wearing a tight corset.[9]

1 Physicians

Victorian doctors worked within the medical knowledge of the day. Most medical procedures were based on trying to restore balance to the body. Thus, laxatives, purges, and leeches were popular as a means of draining foul humors. Also, doctors believed small doses of poison had medicinal properties.

The majority of the time, patients survived despite treatment, not because of it. However, occasionally, the medics hit on something by accident, like prescribing cigarettes to asthmatics. The active ingredient, arsenic (again!), was transported in a tobacco that contained a natural derivative of atropine—which opens up the airways. So the patients did improve, but not for the reason the doctors thought.[10]

+ Anthrax In House Plaster

It’s generally not a good idea to coat the walls of your home with a deadly bacterium. But that’s what the Victorians did—albeit rarely.

Prior to gypsum plaster, walls were lined with lime plaster. This was a mix of lime strengthened with animal hair from goats, cattle, sheep, or horses. While anthrax wasn’t common in Victorian England, it did occur. Products from infected animals, such as skin, hair, or wool, were then a possible source of infection for people.

People can pick up anthrax through the skin abrasions or inhaling it, so let’s hope the hair from a few infected animals never made it as far as wall plaster.[11]

Dr. Pippa Elliott is a veterinarian who is passionate about animals and history. At school, she was described as a “Trivia Queen,” and this is something she has never grown out of.

For more certifiably insane Victorian practices, check out 10 Ridiculous Things The Victorians Did In The Name Of Science and 10 Dangerous Beauty Trends From The Victorian Era.