Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Top 10 Artifacts And Places Frozen In Time

In archaeology, an untouched pot shard is more valuable than a gold statue moved miles from its original stand. To understand the great puzzle of our past, context is crucial.

How and where an unmoved object is found can retrieve authentic history—from previously unknown rituals and chapters of known history to rare information about vanished cultures. Lost cities, art, and even structures known only from descriptions are being seen for the first time.

10 The Unused Roman Oven

In 2014, developers eyed a patch near Falkirk, a town in Scotland. Per law, before the shopping center’s first brick was allowed to land, archaeologists had to sweep the site. The area previously delivered Roman fortifications which heightened the chance of a hidden ancient presence.

After some shoveling and dusting, archaeologists uncovered a familiar structure with a twist. Two sunken chambers formed a trademark 8-shape that connected them. Appearing undisturbed from the day it was built was a 2,000-year-old Roman oven.

Normally, Roman ovens yield the ash and charcoal of ancient cooking. This one was squeaky clean, with no such layers or scorching. In fact, archaeologists suspected that it had never even been used.[1]

Due to the missing morsels of ancient meals, more evidence is needed to confirm its purpose. However, the shape and site suggest that it was a military bread oven. Similar and confirmed bakers’ tools have popped up in Roman camps throughout Scotland.

At the Falkirk excavation, items surfaced that support an army settlement, including hobnails from soldiers’ sandals and a bolt head.

9 The Antarctica Fruitcake

The first buildings in Antarctica were raised at Cape Adare in 1899. Recently, over a thousand artifacts were removed for study and preservation. Included in the haul was a surprise: a 106-year-old fruitcake still wrapped in its original wax paper.

Unlike the rusted cake tin in which it was found, the fruity snack looked ready to serve. A clue to the identity of the person who could not resist bringing fruitcake along to the edge of the world was the bakery’s name on the tin. Huntley & Palmers always provided baked provisions for Robert Falcon Scott, a British explorer.

It was likely left behind when Scott departed from the cabin in a bid to reach the South Pole first. The famous Terra Nova expedition (1910–1913) turned out to be fatal.

His team eventually reached their destination, but Norwegian explorers had beaten them to it a month earlier. Scott’s entire team perished on the return trip when they froze to death. The well-preserved cake, with only a whiff of rancid butter, will be treated with stabilizing chemicals and returned with other artifacts to be displayed in the Cape Adare cabin.[2]

8 Unknown River Tools

Amateur archaeologists investigated an extinct river in Wales and found something that made the experts sit up and take notice. While working at the Bronze Age site in 2017, the amateurs discovered stone tools on the 4,500-year-old streambed.

Numbering about 20, the limestone utensils were triangular and showed signs of heavy use. They ranged from 5 centimeters (2 in) to 22 centimeters (8.6 in) long.

Two things made them uniquely fascinating. They appeared to have been arranged deliberately under the water when the stream still existed. Also, after archaeologists picked each other’s brains, they realized that nobody had ever seen such artifacts before.[3]

The tools were roughly shaped into points, which were scarred and pitted from a mystery purpose. One guess considers the hand tools as engraving stones. During the Bronze Age, rocky surfaces were abundantly adorned with carvings and symbols.

Another half-understood feature stands next to the river near the triangles, although the two have no clear connection other than belonging to the same community. Discovered years earlier, the mound once turned out huge amounts of scalding water. Freshly fired stones heated the water in a pit to likely use for domestic needs.

7 El Castillo’s Queens

Long before the Inca, the Wari people ruled the Andes. They were widespread, but archaeologists struggle to document their culture. Most sites have been irreparably damaged by looters.

In 2013, aerial images of a Wari location showed artificial angles. Archaeologists then visited El Castillo de Huarmey, a pyramid site near the coast in Huarmey.

Incredibly, the lines led to a massive mausoleum below. Not only did looters miss it after repeated raids, but the deceased appeared untouched. Sitting in rows were 63 individuals.

Three women received better burials than the rest. Within the 1,200-year-old hall, each had her own chamber filled with precious metals and artifacts. Identified as Wari queens, it became the culture’s first royal tomb to be discovered intact.

There were weaving instruments and jewelry made of gold. Brightly decorated ceramics and alabaster vessels showed skill in pottery and crafting. Silver jewelry and bronze axes were also present.

However, not everything was cultured behavior by today’s standards. Some women in the tomb are suspected to be sacrifice victims. Insect pupae in the royal remains hinted at a gruesome ritual. The corpses were occasionally removed by Wari citizens and left outside for a while.[4]

6 Timeless Ships

Usually, sunken ships retain a few recognizable characteristics while the rest rot and rust away. The Black Sea is different. Eastern Europe’s major rivers feed a permanent layer of freshwater on top of the heavier seawater. This blocks oxygen from reaching the salty layer. Without oxygen, decay is impossible in the icy depths and doomed ships keep their looks.

When over 40 wrecks were recently found off the coast of Bulgaria, it was like finding a collection of bottled ships from different eras. Together, they cover a thousand years of human history (9th–19th centuries).

Some are so well-preserved that the decks contain coils of rope, carvings, and wooden structures. One medieval ship displayed a captain’s quarterdeck—the first to be physically seen in the archaeological record. It was probably Venetian and the most intact of its type ever discovered.

As a sought-after trade route for many nations, researchers estimate that the time-frozen fleet at the bottom of the Black Sea could number in the thousands.[5] Called “one of archaeology’s greatest coups,” more surprises could wait below deck. In 2002, a Black Sea wreck yielded 2,400-year-old dried fish steaks inside a pot.

5 Burghead Fort

The threadbare history of the Wari looks plentiful against Scotland’s Picts. Most accounts of them are secondhand descriptions. The Romans called the tattooed tribes “Picts” (“painted people”), but their true name is lost.

A Pictish fort, referred to as Burghead Fort, disappeared beneath the town of Lossiemouth in the 1800s. Archaeologists checked in 2015 to see if anything remained. Excavations busted the belief that Lossiemouth wiped out the older settlement.

The diggers found evidence that Burghead was a stronghold of their Northern territory. Inside were major ruins, including a longhouse. The news was exciting because many already thought the fort was an important royal seat. The ruins could reveal the nature of the community, a crucial factor in understanding how power was distributed at Pictish sites.

Inside the longhouse was a coin, minted during the life of English king Alfred the Great. This dated the fort to the ninth century when the Picts had to deal with Vikings and settlers. The coin was Anglo-Saxon, proving that the Picts traded long-distance. But oddly, it was pierced. One theory suggests that perhaps the Picts wore their money on necklaces.[6]

4 House Of The Tesserae

On January 18, 749, artisans were busy installing floor mosaics when an earthquake struck the city of Jerash. The disaster toppled the house and sealed everything as it was that day, including one of the workers.

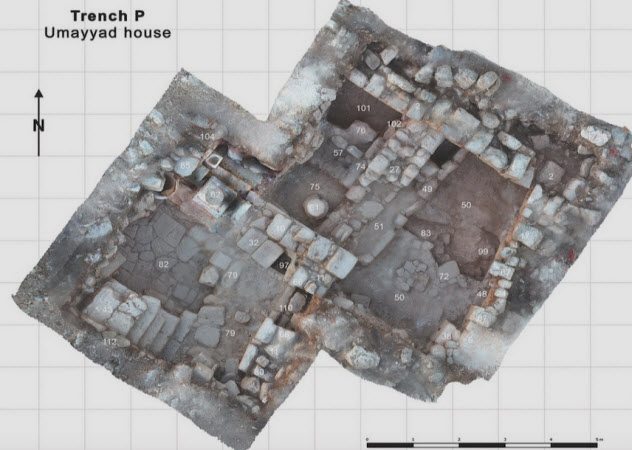

Situated in modern-day Jordan, ancient Jerash is well studied except for the northwest quarter. That was where the “House Of The Tesserae” protected its timeless interior until its discovery in 2017.

Named for the small tiles that wove together the mosaics, the house provided rare insights and answers. It froze the moment before the earthquake struck. The whole house had been emptied beforehand for the extensive redecorating.

Walls were being prepared for painting. The top floor’s mosaic was already completed with geometric designs. The ground level was in progress and gave elusive clues about a certain issue.

For a long time, nobody knew how mosaics during the eighth century’s early Islamic period were made. Were the tiny limestone tesserae cut on-site, or were they created elsewhere? A metal hammer near containers of freshly carved tiles suggests that they were chiseled at the house.[7]

3 The Lost Civilization

Adventurers have hunted the mythical White City of Honduras for decades. In 1940, explorer Theodore Morde came back from the Mosquitia rain forest, claiming to have found it. Fearing looters, Morde never disclosed the location.

In 2012, an aerial scan detected man-made features under Mosquitia’s forest canopy. For more than a mile were signs of buildings and water canals. Three years later, a ground expedition braved unexplored swaths of jungle to see what was going on down there.

What they found was dramatic.

The team walked into an untouched lost city with plazas, earthworks, mounds, and an earthen pyramid. Near the pyramid were 52 half-buried statues, among them a snarling jaguar head, ceremonial stone seats, and vessels.

The carvings were possibly part of the city’s last rites, ritually offered before the place was abandoned. Crafted between AD 1000–1400, their undisturbed positions, along with the rest of the pristine city, offer a unique opportunity to view a civilization so unknown that it has yet to be given a name.[8]

Whether this is the legendary White City remains to be seen. To protect valuable clues from destructive looters, the location remains secret.

2 The Soldiers Before Hadian’s Wall

The 117-kilometer (73 mi) wall in Northumberland was raised in AD 122 to defend Rome’s frontier in Britain. In 2017, a floor of the fourth-century fort of Vindolanda was lifted with little expectation.

Instead, they encountered the living quarters of some of the first soldiers tasked with keeping the locals under control. The barracks were built in AD 105, long before Hadrian’s barrier, and belonged to a cavalry unit of about 1,000 men.

Cavalry weapons, including exceptionally rare swords, and horse tack littered the floors. Toys and personal possessions showed that the soldiers’ families also lived there.

Around 30 years after the camp was apparently abandoned in a panic, the Romans returned. They poured concrete for new barracks and sealed thousands of artifacts in an oxygen-free state. Things that usually rot remained pristine—wooden tablets, leather, and cloth. Riding equipment shone, and strap junctions retained their alloy links, a highly scarce occurrence.

The collection allows a priceless study of those who lived in the hot zone when the Britons rebelled, possibly the reason why the camp fled. It is also valued for adding a unique chapter to the prelude to Hadrian’s Wall.[9]

1 Tall el-Hammam

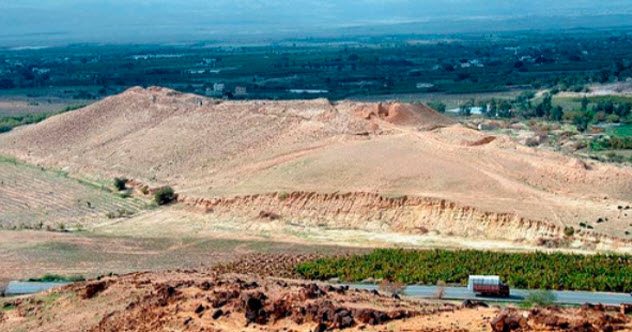

The biblical city of Sodom, destroyed by God for the debauchery of its residents, was described as the biggest settlement in Jordan’s eastern side during the Bronze Age. In 2005, archaeologists chose the relatively unstudied Tall el-Hammam as a candidate.

The monumental mound was at the right place and was the biggest Bronze Age site even outside of the required region. A decade of excavations revealed the remarkable builders who had managed Tall el-Hammam as a powerhouse while other cities in the area folded.

Archaeologists describe the scope of the city-state as “monstrous.” Ancient construction continued from 3500–1540 BC, adding formidable defensive walls and ramparts, towers, plazas, buildings, monuments, and a palace. The rampart system alone consists of millions of bricks and forms a fortified superstructure over 30 meters (100 ft) tall.[10]

Like many ancient cities, Tall el-Hammam came to a sudden and mysterious end. That the city-state previously survived factors that had killed off the surrounding great cities makes it even stranger.

After 700 years as a veritable ghost town, a new population grew during the Iron Age II period (1000–332 BC). More building was done, some of it great, but nothing ever equaled the glory of the Bronze Age again.

Read about more intriguing artifacts on 10 Enigmatic Gold Artifacts and 10 Fascinating Ivory Artifacts Shrouded In Mystery.