Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Strange Things People Used To Believe About Animals

Zoology wasn’t always a precise science. Thousands of year ago, people like Aristotle and Pliny the Elder did their best to compile everything anyone knew about animals into massive, encyclopedic tomes. But they didn’t always get the details right.

Before airplanes, cameras, and Google, most people had never seen an elephant. If they wanted to know what an elephant looked like, their only option was to ask someone who had—and they pretty much had to believe whatever they heard. Sometimes, they wrote those crazy answers down—and for nearly 2,000 years, people around Europe just accepted these things as true.

10 Elephants Constantly Fight Dragons

The Greeks and the Romans were fascinated by elephants. They’d seen them in India and Africa and were convinced that they were the smartest creatures on the planet. It was a reasonable belief. They’d already trained elephants to do some incredible things, from walking on tightropes to tracing Greek letters with a brush. And so people were ready to believe anything they read or heard about elephants.

“When an elephant happens to meet a man in the desert,” one Roman encyclopedia said, “[and realizes the man is lost, then] the elephant . . . points out the way.”[1] But as reliable as they were at giving directions, the book warned, it was difficult to get an elephant on a boat. An elephant would refuse to board until somebody promised that it would get home safely.

The same book claimed that dragons were “perpetually at war with the elephant.” In India, dragons were constantly swooping down on elephants and trying to crush them, hungering to eat their cold blood. A particularly alert elephant, however, could knock a dragon down and crush it underfoot.

It’s all pretty weird, but it doesn’t seem like anyone bothered to correct it. Over 100 years after that book was published, another one came out making most of the same claims. But it added one fun extra detail. This book said that elephants reproduced by eating a magical root that made babies spontaneously appear in their wombs.

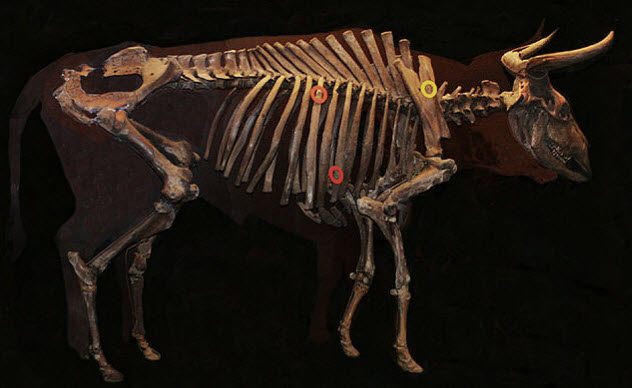

9 Aurochs Have Projectile, Toxic Poop

Milk cows and every kind of domestic cattle are descended from one animal: the aurochs. The last aurochs died out about 400 years ago. But if the Greeks and the Romans are to be believed, the world’s a less disgusting place without them.

According to the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, aurochs had horns that were bent inward. When a predator attacked them, their horns were totally useless.[2] So they had to rely on the one defense God gave them: running away and pooping.

“While in the act of flying,” Pliny claimed, “it sends forth its excrements.” They could shoot it out far, too—about 1.2 meters (4 ft), according to Pliny. Their projectile poop did more than just gross out their predators. It burned them like fire.

Pliny’s stories about the weaponized poop of aurochs were believed well into the Middle Ages. He wasn’t the only one telling people it was true, though. Aristotle backed up every word Pliny said, except for one. About 1 meter (4 ft), he claimed, was a low estimate. Aurochs could easily poop on a target 1.8 meters (6 ft) away.

8 Salamanders Can Put Out Fires

For a good 1,000 years or so, humans as a species were fairly sure that salamanders were magic. They were so cold, Romans believed, that they could extinguish a fire just by touching it.

That claim also came from Pliny the Elder. But this time, he actually bothered to check his facts. After telling all of Rome that salamanders had magical fire-extinguishing powers, he threw a salamander into a fire himself. To his disappointment, the animal wasn’t magic. It was just dead.

Nobody seems to have listened to him, though. About 1,000 years later, the Jewish rabbi Rashi was still writing about salamanders’ amazing magical powers, even telling people that they could become fireproof by covering themselves with salamander blood.

He also insisted that salamanders were born in fires. Specifically, he said that a new salamander is born when a glassblower leaves his furnace ignited for seven consecutive days. After the seventh day, Rashi insisted, a newborn salamander will crawl out of the fire.[3]

7 Eels Grow Out Of Mud

According to ancient writers, salamanders aren’t the only animals that spontaneously burst into existence. Aristotle was convinced that a lot of animals did. He tried to persuade the world about a few different cases of what he called “spontaneous generation.” But the one that really stuck was his idea that eels magically grow out of mud.[4]

For more than 2,000 years, nobody even questioned Aristotle’s “eels just magically appear” theory. Not everybody agreed on how it happened, though. Pliny said they made babies by rubbing against rocks, while the 17th-century English writer Izaak Walton insisted that they grew out of “a particular dew falling in the months of May and June.”

But everyone agreed on the main detail: Eels are a gift from God.

It took until the 19th century before anyone was able to prove that eels actually reproduced. The problem was that no one could find their reproductive organs. Finally, though, the world created a man who was willing to poke around at people’s private parts long enough to figure it out: Sigmund Freud.

That’s right. Before he became the father of psychology, Freud was the man who solved the mystery of how eels get nasty.

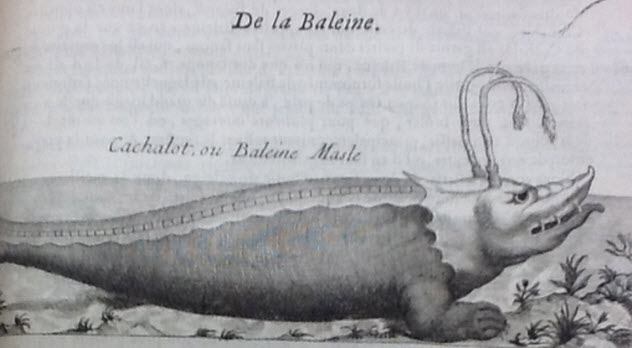

6 Whales Have Antennae

In the 17th century, a Frenchman named Pierre Pomet released a book on the natural world that was filled with illustrations of the strange animals that inhabit our Earth. Each picture was full of beautiful, vivid details of what these strange creatures looked like—all drawn based on what Pomet had seen when he closed his eyes and imagined really, really hard.

Pomet’s whales, in particular, looked a bit strange. He insisted that one could tell a male whale from a female whale by their heads. According to Pomet, the males had hands with fingers, a long sheet of metal on their backs, and massive, armored heads like the kind you’d see on a Chinese dragon. And on top were two long antennae, each with a fluffy little pom-pom on the end.[5]

His female whales were a bit closer to real life, but they still had antennae. Pomet insisted that these antennae were the key to telling the genders apart. On the females, he claimed, the antennae were much shorter and stubbier.

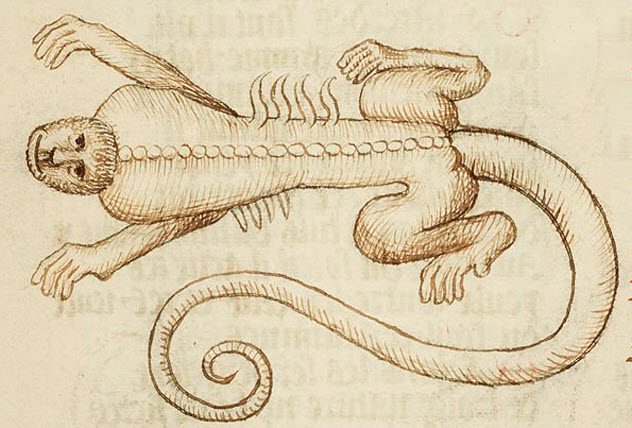

5 Crocodiles Are Basically Just Monkeys

Ancient civilizations had a decent grasp on what crocodiles were, but somehow, we lost track of it by medieval times. That becomes clear when you see the animals labeled as “crocodiles” in the Book of Flowers, an 11th-century encyclopedia, because they’re pretty much just monkeys.

According to the Book of Flowers, crocodiles have long, curly tails, hands, and hairy faces. It’s a strange description, and it would be easy to think that they just got the names mixed up. But their vision of crocodiles isn’t purely monkeys. The bodies of these creatures are long, hard, and scaly like a real crocodile’s. They just happen to have monkey heads on top.[6]

Over the next few hundred years, our ideas about crocodiles didn’t get much better. Later medieval artists started getting the tails right but kept the monkey faces. Others gave these animals massive, horselike legs or made them look like dogs with scales. As nobody who’d actually seen a crocodile ever bothered to correct them, European artists kept drawing crocodiles that way until about the 17th century.

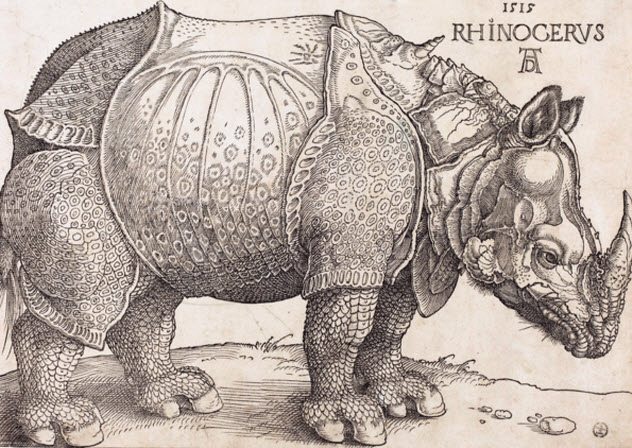

4 Rhinoceroses Hate Elephants

According to Pliny the Elder, rhinoceroses and elephants absolutely hated each other. The second they saw each other, Pliny the Elder claimed, they would start brawling, duking it out in an incredible battle of the titans.

His stories about rhino-on-elephant violence were so widespread that Manuel I, the 15th-century king of Portugal, decided to test them out. He had a rhinoceros and an elephant sent to his country and pitted them in a battle royal.

It didn’t quite go as planned. As it turned out, elephants are lovers and not fighters.[7] As soon as the elephant saw the rhinoceros, the elephant just ran for its life.

Even so, Manuel’s experiment didn’t lead to a better understanding of animals. Instead, stories about his rhinoceros spread around Europe, getting crazier every time someone told it.

A German woodworker named Albrecht Durer became so enthralled by the stories that he sat down and drew a picture based on what he’d heard. His rhinoceros had scaly legs and hard, armor-like plates on its back. Durer left notes saying that the rhinoceros is “the color of a speckled tortoise [and is] covered with thick scales.”

3 Bees Can Be Killed By A Menstruating Woman’s Stare

Pliny the Elder wasn’t just confused about animals. He had strange ideas about women, too. He especially couldn’t understand menstruation, except that it was something that ought to be feared. The stare of a menstruating woman, he insisted, could kill. “A swarm of bees, if looked upon by her,” he warned, “will die immediately.”[8]

As much as ancient bees had to struggle through the peril of women on their periods, though, they had an amazing superpower. Dead bees, Pliny insisted, could be brought back to life by covering them with mud and the body of an ox or a bull.

Later generations of writers didn’t fully agree with Pliny that bees could be brought back to life. But they were fairly sure he was onto something about that bull thing. Saint Augustine and Isidore of Seville were sure that bees were incapable of having sex. Instead, they believed that bees spontaneously generated out of the rotting flesh of cows.

2 Vipers Eat Each Other When They Reproduce

According to the Greeks and the Romans, having babies was a horrible experience for vipers. But they had no choice: If they were going to reproduce, both viper parents had to die.

When two vipers reproduced, the Greeks and Romans claimed, the male would stick his head into the female’s mouth and spit semen at her. The female would get so excited by this that she would bite down and chomp the male’s head off.

But her time was coming, too. She would soon start growing up to 20 children inside her womb, and they would be so excited to get out that they would eat their way through her belly.[9]

It was a weird story, but it became even stranger over time. By the third century AD, Roman writers were not only telling people that vipers had these brutal mating rituals, the writers were also saying that vipers looked like human beings. “The male viper resembles a man,” a book called the Physiologus said, “and the female resembles a woman to the waist, but below the waist she has a crocodile’s tail.”

1 Pelican Blood Can Bring The Dead Back To Life

In the seventh century, a writer called Isidore of Seville made a strange claim about pelicans: These birds have magical blood that can resurrect the dead.

He claimed that being resurrected from the dead was a rite of passage for pelicans. When a young pelican matured, it would be murdered by its mother. The mother would mourn its children’s deaths for three days and then start pecking at its own chest until it bled. As the blood fell on the mother’s dead children, the pelicans would come back to life.[10]

Isidore didn’t seem fully convinced by his own story, and it probably should have been passed off as a legend. But instead, everyone accepted it as the gospel truth. By the 13th century, several books backed up his story as scientific fact.

By the 16th century, a pelican stabbing itself was the official symbol of Queen Elizabeth. It was even on the cover of the first edition of the King James Bible.

Read more strange things about ancient animals on 10 Animals Worshipped As Holy and 10 Facts About Ancient Egyptian Animals That Will Blow Your Mind.