History

History  History

History  Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

10 Wild West Stories With Modern Developments

The Wild West ended over a century ago, but many of its characters live on thanks to pop culture. Their staying power is a testament to the popularity of these lawmen, outlaws, frontiersmen, and folk icons who shot their way into the history books. Of course, over the decades, we might have romanticized the era a bit, and Hollywood chipped in as well, so our image of the Old West might not be entirely accurate.

Legends and exaggerations aside, the Wild West still holds great interest for history buffs. And, just like with other historical periods, we’ll occasionally learn new things regarding affairs thought truly dead and buried a long time ago.

10 No Pardon For Billy The Kid

In 2010, the governor of New Mexico brought into discussion a potential pardon for one of the country’s most notorious outlaws—Billy the Kid.

This was due to a pardon that the Kid was supposedly offered back in 1879 by Lew Wallace, then governor of the New Mexico Territory and, coincidentally, the man who wrote Ben Hur. The deal came in exchange for Billy testifying before a grand jury about a murder he witnessed. While the outlaw fulfilled his side of the bargain, for some unknown reason, Wallace never followed through on his end. Back in 2010, in his final weeks in office, Governor Bill Richardson thought that it might be finally time for the state to pardon Billy the Kid.

Even over 130 years later, this proposal stirred up a heated debate. Strongly opposing the pardon were descendants of Sheriff Pat Garrett, the famed lawman who gunned down Billy. They argued that the Kid was, ultimately, a cop killer. They also worried that his pardon would tarnish their ancestor’s reputation.

Governor Richardson denied the pardon.[1] He believes there are enough historical records to attest that a deal was struck between Wallace and Billy, but he is not privy to the motives his predecessor had for rescinding the offer. Richardson also took into consideration the fact that Billy continued his criminal ways and killed two lawmen after the deal fell through.

9 Finding The Murder Weapon In The Deep Creek Murders

In 2013, former Idaho representative and amateur historian Max Black found the likely murder weapon used in a double murder over 120 years ago.

Back in 1896, a minor sheep war was taking place in Twin Falls County, near the border between Idaho and Nevada. A sheep war refers to a conflict between shepherds and cattlemen over grazing rights that turns violent. In this particular case, two Mormon sheepherders named Daniel Cummings and John Wilson crossed into Cassia County to graze, even though it was cattle territory. Their bodies were found a few weeks later.

The prime suspect in the murders was Jackson Lee Davis—better known as “Diamondfield Jack.” He was quickly found guilty and sentenced to hang. However, before the execution, two other men named Jim Bower and Jeff Gray confessed to the killings, claiming they acted in self-defense after being attacked by the sheepherders.

In modern times, Black used court records to locate the crime scene. He searched the area with a metal detector and found a .44 slug. He took it to a local firearms expert to verify its age, and he revealed that someone brought him a rusted 1878 Colt Frontiersman he’d found in the same area.[2] Black became convinced it was Jim Bower’s gun, which he allegedly lost during the shoot-out. It was the right make and model and had its sight filed off.

8 The Execution Of Wild Bill Longley

Wild Bill Longley claimed to have killed 32 people. However, he told many tales about his adventures, many of them likely fictitious, so it’s hard to say what was true and what wasn’t. He claimed to have gunned down eight black people once after losing a a bet on a horse race. Another time, he allegedly escaped an attempted lynching after someone shot at him, hitting and cutting the rope he was hanging from.

Longley was supposedly executed in Giddings, Texas, in 1878. By this time, he had become a Roman Catholic and had whittled down his self-confessed kill count to eight. According to legend, his family bribed the local sheriff, who used a trick rope during the execution. The casket was filled with stones, and the real Longley lived out his years in Louisiana under a different name.

Forensic anthropologist Douglas Owsley began investigating this story back in 1986. The biggest issue was locating Longley’s casket, as he was buried outside the town’s cemetery in an unmarked grave. It took 15 years, but he finally found it with the help of geologist Brooks Ellwood. It was filled with bones, not rocks, which was a promising start. Afterward, he enlisted the help of a DNA lab. They recovered a sample from the skeleton’s tooth and positively matched it to Helen Chapman, one of Longley’s sister’s granddaughters.[3]

Furthermore, the casket contained a Catholic medal and a celluloid flower, both items Longley carried with him to the scaffold. There was no doubt: Wild Bill Longley was executed that day.

7 Did Butch Cassidy Make It Out Of Bolivia?

As one of the most iconic characters of the Wild West, it’s only normal that legends surrounded Butch Cassidy, the leader of the notorious Wild Bunch. Particularly, a lot of stories came about following his demise, which is still somewhat shrouded in mystery.

On the run from the law in South America, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid supposedly met their ends in 1908 in a shoot-out with Bolivian police. However, local authorities never identified the bodies as anything other than two bandits who robbed a payroll transport. They were buried in unmarked graves in San Vicente, and subsequent attempts to find their remains and DNA-match them failed. Naturally, this started rumors that Cassidy survived his encounter and lived on for decades under a new name.

During the 1970s, there was a new hypothesis, primarily promoted by author Larry Pointer, claiming that Cassidy assumed the name “William T. Phillips.” The latter was an author who published a biography on Butch Cassidy in 1934, titled The Bandit Invincible. According to believers, the book contained intimate details that could have only been known by the famous outlaw himself.

The idea persisted for decades, and it wasn’t until 2012 that Pointer finally changed his tune. This was when researcher Jack Stroud presented the hypothesis that William T. Phillips was the alias of someone who did time with Cassidy in Wyoming State Prison, specifically one William T. Wilcox.[4] Besides the obvious similarity of the names, there is also a strong resemblance between Wilcox’s mug shot and later photographs of Phillips.

6 Where To Bury John Wesley Hardin?

John Wesley Hardin was not a nice man. In fact, he can be considered one of the most dangerous gunfighters of the Old West, with up to 42 kills to his name. According to one story, Hardin once shot a man just for snoring. He was eventually gunned down in 1895 by John Salmon in El Paso, Texas, and buried in the city’s Concordia Cemetery.

A century later, a bizarre legal battle erupted over his remains.[5] A group of people from the small town of Nixon, Texas, showed up with a disinterment order at the El Paso cemetery, looking to dig up what was left of Hardin and rebury him in their little community. They were met by local officials and historians, who stopped them with an injunction. What followed were several years of lawsuits and appeals until a court ruled to keep the body in El Paso.

The Nixon group claimed to represent Hardin’s descendants (although none of them lived in the town). They argued that, as a family man, Hardin should be buried in the place where he married his first wife and had his children. More importantly, they asserted that survivors had final say over their relatives’ burial spots.

The El Paso group saw this as nothing more than a publicity stunt meant to bring tourists to Nixon. As far as the survivors’ law was concerned, they argued that Hardin’s lover, Beulah Morose, paid for his funeral expenses, so her descendants should have final say.

5 Who Killed Pat Garrett?

The demise of Sheriff Pat Garrett has long rested under a cloud of mystery with many people, including his descendants, who question the official story.

Garrett was killed on February 29, 1908, in Las Cruces, New Mexico. He was traveling with two men named Jesse Wayne Brazel and Carl Adamson, hoping to resolve a land dispute. Garrett had leased a ranch to Brazel who, against the former lawman’s wishes, used it for goat grazing. Eventually, the two agreed to cancel the lease if they found a buyer for Brazel’s goat herd, which is where Adamson came in.

For whatever reason, Brazel shot Garrett and then turned himself in, pleading self-defense. However, he was acquitted after a one-day trial, and Adamson, the only eyewitness, was never called to testify.

This version of events raised eyebrows, and talk soon began of a plot to kill Pat Garrett, possibly organized by rancher W.W. Cox to gain his land. Also implicated was notorious gun-for-hire Jim Miller, who might have waited for the trio in ambush. Historian Leon Metz said in his 1974 biography of Pat Garrett that the sheriff’s family believed Carl Adamson was the killer. Regardless of the real shooter’s identity, most agreed Brazel was there to take the blame because he had credibility and a clean record.

A new clue in the mystery emerged in 2017: Pat Garrett’s long-lost coroner’s report.[6] It was uncovered by an employee for the Dona Ana County Clerk’s Office who was going through boxes of old records. It was signed by seven members of the coroner’s jury and concluded that Wayne Brazel killed Pat Garrett. It remains to be seen if this new evidence will strengthen the validity of the official story.

4 How Did Davy Crockett Die?

Known as the “King of the Wild Frontier,” Davy Crockett has become one of America’s greatest folk heroes. His larger-than-life adventures were first popularized by newspapers, almanacs, and plays and greatly enhanced by a 1950s Disney miniseries.

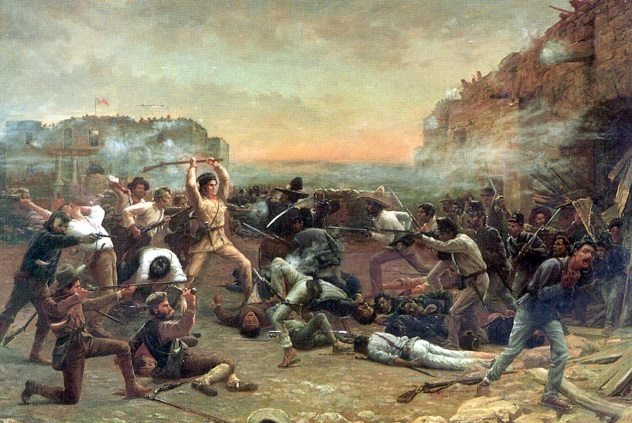

Crockett’s demise was a core part of his legend. During his last stand at the Battle of the Alamo, the frontiersman died fighting valiantly against Mexican troops. However, in 1955, an author named Jesus Sanchez Garza published a book that claimed otherwise. Allegedly based on memoirs of a Mexican officer present at the Alamo named Jose Enrique de la Pena, the book said that Crockett was one of several men who were captured and executed.

At first, the book was completely overlooked. However, two decades later, when it was finally translated into English, it sparked outrage in the United States. Historians were quick to defend Crockett’s reputation and pointed out several issues which questioned Garza’s credibility. For starters, his book was self-published. He never explained how he obtained de la Pena’s memoirs and presented his account shortly after the release of the Disney show, at the peak of Crockett’s popularity.

These reasons were enough for many historians to dismiss the account as fake. However, in 2000, a forgery expert declared the memoir authentic.[7] David Gracy of the University of Texas at Austin evaluated the materials and watermarks of the papers and deemed it consistent with paper used by the Mexican Army at the time. He also found no signs of tampering throughout the 680-page document. This doesn’t mean that what the memoirs say is necessarily true, but they seem to belong to someone who witnessed the event.

3 The Mummy Of The Wild West

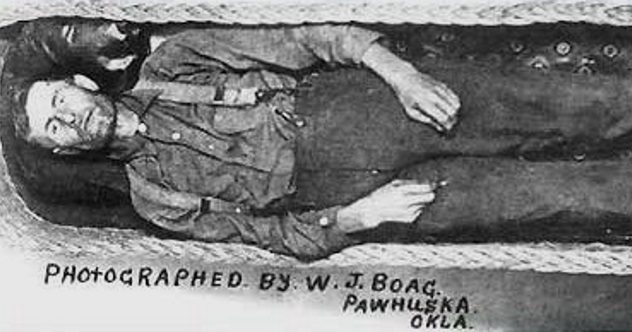

Back in the 1970s, the crew working on The Six Million Dollar Man TV show was scouting for locations to shoot scenes set in an abandoned carnival. They settled on The Pike, a disused amusement park in Long Beach. Later, during filming, crewmen needed to move a mannequin hanging from the gallows in the House of Horrors. They pulled on it until an arm tore off. Inside, they were shocked to discover a human bone and realized that their “mannequin” was actually a mummified corpse.[8]

The mummy was identified as Elmer McCurdy, an outlaw from the last days of the Old West. He died in 1911 in a shoot-out following a failed train robbery. With nobody to pay for his funeral services, the undertaker who embalmed McCurdy decided to keep him, dress him up, and display him as an exhibit to recoup his losses. McCurdy proved to be quite popular and became known as “The Embalmed Bandit.”

Over the decades, McCurdy appeared in many carnivals and sideshows. During this time, his skin hardened, his body shrank to the size of a child, and he was coated in several layers of glow-in-the-dark paint. That’s how the TV crew found him in 1977. He was finally buried in the Boot Hill section of Summit View Cemetery in Guthrie, Oklahoma, next to fellow outlaw Bill Doolin.

2 Did Jesse James Fake His Death?

Like Butch Cassidy, Jesse James’s fame was so great that rumors of his survival inevitably sprang up. James was killed in 1882 by a former member of his gang, Robert Ford, who wanted to collect the bounty on the outlaw’s head.

Public opinion was divided on the death of Jesse James. Many people saw Ford as a coward for betraying his “friend” and shooting him in the back. Ford himself was gunned down ten years later by Edward Capehart O’Kelley.

There was a hypothesis that Jesse James faked his death, with Ford’s help, to evade justice. (Presumably, the theory held that the body that was photographed was another man’s.) The story gained more prominence in the late 1940s, when a centenarian named J. Frank Dalton came forward claiming to be the famed outlaw.

Many historians and biographers never took the stories of James’s survival seriously, but the idea was pervasive enough that in 1995, his body was exhumed and subjected to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) typing. While the remains were poorly preserved, two teeth and two hairs provided mtDNA samples which proved identical to DNA samples taken from two of Jesse James’ maternal relatives.[9]

Still, the idea persisted. In 2000, a judge signed an exhumation order for J. Frank Dalton after years of appeals. However, due to a headstone mix-up, the wrong body was dug up. A second order has yet to be issued. For some, the mystery remains alive.

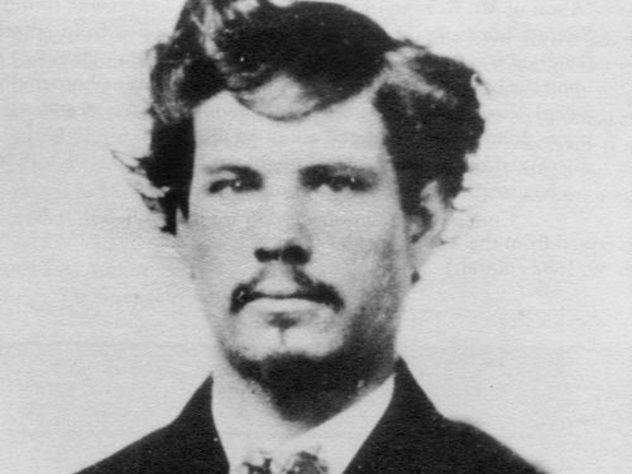

1 Who Killed Johnny Ringo?

Johnny Ringo was an outlaw considered to be the leader of the Cochise County Cowboys, a loosely organized group of gunslingers. The Cowboys are primarily remembered for their feud with the Earp brothers and the famed Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, where three of them died. Less than a year after that shoot-out, Johnny Ringo was shot in the head. The question still remains today: Who killed him?

Wyatt Earp was always at the top of the suspects’ list. He had motive, as Ringo was possibly involved in the assassination of Morgan Earp and the attempted murder of his brother, Virgil. During the 1920s, an aging Earp even admitted to the deed to several writers. The timelines didn’t line up, though. When Ringo was shot, Earp had already fled Arizona after his infamous Vendetta Ride. Others believed it was Doc Holliday taking revenge on his friend’s behalf, but the timeline puts him in Colorado. Two other suspects were “Buckskin” Frank Leslie and Michael O’Rourke, although there’s only hearsay supporting their stories.

The coroner’s inquest ruled Ringo’s death a suicide. However, many dismissed this notion, seeing it simply as the county closing the case on the unsolvable murder of a violent criminal. People found discrepancies that contradicted the suicide angle. Why was his cartridge belt upside down? Why was there a small piece of scalp missing? Crucially, why were there no powder burns on his temple?

In 2002, author Steve Gatto published his biography on Johnny Ringo, in which he agreed with the suicide verdict and offered possible explanations for the mysteries. He believes Ringo put his belt on upside down because he was drunk. John Yoast, the man who found his body, could have taken a piece of scalp as a souvenir. Most importantly, though, Gatto asserts that the coroner’s report makes no mention of the presence or absence of powder burns because the body had turned black due to decay.[10]

Read more about the Wild West on 10 Horrifying Stories Of Life In The Wild West and 10 Crazy Characters From The Wild West.