History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Criminal Writers With Real Skeletons In Their Closets

Writing can sometimes be seen as a kind of therapy, and people with traumatic pasts are often advised to write down their experiences. After all, authors are usually encouraged to write what they know.

However, some people’s backgrounds are more colorful than others. And for those with secrets in their past, writing from experience can prove difficult and sometimes even dangerous.

Here, we take a look at 10 authors who really wrote from experience.

10 Liu Yongbiao

The Chinese crime writer Liu Yongbiao had already penned a number of crime novels when he wrote the introduction for his book The Guilty Secret. In it, he talked about his forthcoming novel, The Beautiful Writer Who Killed, which featured, as advertised, a good-looking writer who gets away with murder. A series of murders, in fact.

Liu was a member of the Chinese Crime Writer’s Association and had already had one of his novels serialized into a major television show. He spoke about his ambition to get The Beautiful Writer Who Killed turned into a movie.

One with a twist presumably. Twenty-two years earlier, Liu Yongbiao had committed four murders. Along with an accomplice, Liu had attempted to rob a hotel guest. When he resisted, they killed him. To cover up the crime, they also murdered the hotel proprietor, his wife, and their 13-year-old grandson.

Liu Yongbiao never did publish The Beautiful Writer Who Killed. He was sentenced to death for his crimes, a sentence which was swiftly executed. His last act as a writer was a letter to his wife confessing to the crimes and saying, “Now I can free myself of this spiritual torment I’ve had for so long.”[1]

9 Kenneth Halliwell

Kenneth Halliwell was the lover of the playwright Joe Orton. Though they had written a number of books together, Orton’s fame began to eclipse Halliwell’s and a jealous rift sprang up between them.

Halliwell had lived a troubled life. He had witnessed the accidental death of his mother when he was 11. At age 23, he discovered the body of his father, who had gassed himself in the oven.

In 1962, while both were up-and-coming writers, Orton and Halliwell were sentenced to six months in separate prisons for defacing library books, a sentence which seems ridiculously harsh. Perhaps it was the homosexual innuendo in the graffiti that ticked off the judge.[2]

On their release, Halliwell’s career foundered while Orton’s took off with such hits as Loot. Halliwell believed that he had taught Orton how to write. So Halliwell found it particularly galling when Orton’s work was a wild success and his own sank without a trace.

In 1967, in a fit of jealous rage, Halliwell fatally attacked Orton by repeatedly hitting him over the head with a hammer. Then Halliwell ended his own final chapter by taking an overdose of sleeping pills.

8 Richard Klinkhamer

In 1992, Richard Klinkhamer, a minor Dutch writer, entered his publisher’s office with a new manuscript called Wednesday, Mince Day. It explored seven possible ways that Klinkhamer might have killed his wife and disposed of her body. As his wife had been missing for a year at that time, it seemed in poor taste. The publisher turned down the book, saying it was “too gruesome.”

Authorities had almost immediately suspected Klinkhamer of murdering his wife. Despite thorough searches of his home and garden, they found nothing, even with infrared scanners. Without a body, the police could do nothing.

However, rumors of his guilt persisted, particularly once news of the manuscript surfaced. In 1997, Klinkhamer sold the family home and moved away with his new girlfriend. The new owners settled in at Klinkhamer’s old house.

Nothing more was heard of Klinkhamer’s wife, Hanny, until three years later when the new owners decided to remodel the garden and take down an old shed. They discovered her body buried under the concrete floor.

Richard Klinkhamer was arrested and charged with murder. His publisher suddenly had renewed interest in his book. However, with a murder charge looming, Klinkhamer finally realized the importance of discretion and declined the offer to publish.[3]

Ultimately, Klinkhamer was sentenced to seven years in prison for manslaughter but was released after two for good behavior. He died in 2016 at age 78.

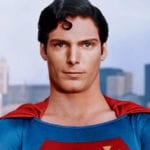

7 Jack Unterweger

The life of Jack Unterweger seems to have been both strange and brutal. Born in 1950, he was the son of an Austrian prostitute and an American GI who abandoned her after the war. Unterweger was brought up in Austria by his aunt, who was also a prostitute. After she was murdered by a client, Unterweger was raised by his grandfather, an alcoholic who beat the boy viciously.

Given this inauspicious start, Unterweger soon turned to crime. In 1974, he murdered 18-year-old Margret Schafer. He told the court that he saw his mother’s face at the moment he killed Schafer and strangled her with her own bra in a rage at the way he had been abandoned when young.

He was sentenced to life in prison. While there, he began to read widely and even write his autobiography, which he titled Purgatory. The book was critically acclaimed, and his honesty and articulation led many readers to petition for his early release.

Unterweger was paroled in 1990 after serving 15 years in prison, and his release was widely welcomed. The governor of the prison remarked, “We will never find a prisoner so well prepared for freedom.”

Unterweger became something of a celebrity, appearing on talk shows and giving press interviews. However, in September 1990, the body of a murdered prostitute was discovered. She had been strangled with her own underwear. This was followed swiftly by another death a few weeks later.[4]

In 1994, Unterweger was found guilty of killing nine more women and was sentenced to life in prison. The day after his sentencing, Jack Unterweger hanged himself with his bootlaces in prison.

6 Francois Villon

Born in Paris in 1431, Francois Villon is considered one of France’s greatest poets. His most celebrated work is Le Grand Testament, a huge document which showed off his mastery of the poetic form as well as his musings on such delights as old age, sickness, and his fear of death.

However, Villon was also a definite scoundrel who spent large portions of his life in jail. In 1455, Villon was involved in a brawl and ended the fight by stabbing a priest with his dagger. Although he was initially condemned to death, his punishment was amazingly reduced to being banished from Paris and even this meager sentence was quickly commuted by a royal pardon. Soon after his return, he led a gang that stole gold coins from the University of Paris and was banished again.

During one of his periods of incarceration, Villon wrote that he regretted his former behavior, but his rehabilitation didn’t last. Several more brushes with the law followed. After his arrest for another brawl, Francois Villon fled Paris for the last time and was never seen again.[5]

5 Thomas Griffiths Wainewright

Thomas Griffiths Wainewright was a talented artist and writer. His paintings can be found hanging in the Australian National Portrait Gallery, and his writing was published in the London Magazine, an influential literary magazine of the day.

His first foray into both crime and writing came in 1817 when he began to forge signatures on checks in his cousin’s name for large amounts of money. Then Wainewright’s sister-in-law, Helen, died suddenly, soon after she had taken out multiple life insurance policies.

Helen had been a fit, healthy woman of only 20 years who had no reason to be contemplating her mortality. Suspicions were raised, following which the insurance companies refused to pay out.

On analysis, Helen’s body was said to show signs of strychnine poisoning, though this could not be proved. During the ensuing court case, suspicions were further raised about the deaths of Wainewright’s uncle, mother-in-law, and sister-in-law.

They had all died in odd circumstances, though no charges were ever brought for these deaths. In fact, no charges could be brought even in relation to his sister-in-law as definitive tests for strychnine poisoning did not exist at that time.[6]

However, during the investigation of Wainewright, the earlier forgeries were uncovered and he was sentenced to transportation to Australia for life. After working on a chain gang for a number of years, Wainewright was allowed some limited freedom after developing a terminal illness. He concentrated once more on his writing and painting, specializing in portraits of his fellow convicts.

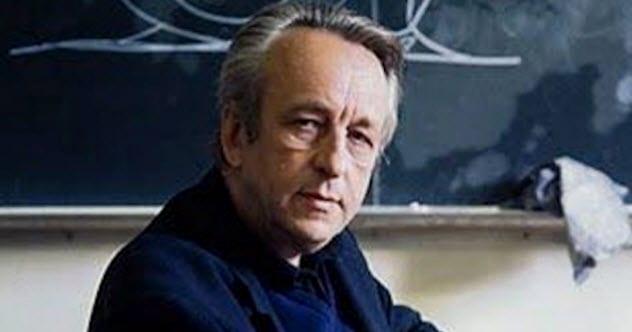

4 Louis Althusser

Louis Althusser was a Marxist philosopher. Born in France in 1918, Althusser joined the French army at the outbreak of World War II, was captured by German troops in 1940, and spent the remainder of the war in a POW camp. His experiences affected him greatly and shaped his philosophical and political opinions.

In 1948, he joined the French Communist Party and took a post at a Paris university. Althusser seemed to live the life of a quiet intellectual. He wrote a number of philosophical works on Marxism, lectured, and lived modestly with his wife.

In 1980, he appeared to have a nervous breakdown. He strangled to death his wife of 30 years while in a manic-depressive state that he claimed he could hardly remember. Althusser was declared unfit to stand trial and spent some time in mental institutions before returning to academia.

However, his memoirs, published posthumously at his request, told a different story about his wife’s death and the whole of his life. Althusser confessed that he wasn’t particularly well-read, hadn’t made a great study of the works of Karl Marx, and frequently plagiarized the work of others. Far from being the great philosopher that the French public believed him to be, he maintained that he had spent his life perpetrating a fraud.

Althusser described the death of his wife in great detail, although he claimed to have been in the midst of a manic episode at the time and could barely remember a thing about it. He seemed to take great pleasure in describing the way he had “caressed” his wife’s throat as he strangled her.[7]

3 Mary Lamb

Mary Lamb had a difficult life. With no formal education, she had taught herself to read and write. From a young age, she was responsible for the care of her invalid mother. Like her brother, Mary had suffered bouts of severe mental illness.

In 1796, Mary stabbed her mother to death while in the midst of a manic episode. She was declared insane and placed in the care of her brother, the writer Charles Lamb.

In 1807, Charles Lamb published Tales from Shakespeare, a retelling of Shakespeare’s stories for children. The book was wildly successful and has never been out of print.

Charles’s name alone was on the title page of the book. However, it was written largely, if not completely, by Mary. It contained 20 stories, of which Mary is now known to have written at least 14.[8]

Mary outlived her brother by over a decade. After his death, she spent much of this time in an asylum. She did not receive any public recognition for her work during her lifetime.

2 Harry Horse

Harry Horse was a children’s author and illustrator who moved to the Shetland Isles, 161 kilometers (100 mi) off the coast of Scotland, with his wife of over 18 years. Mandy had been diagnosed with an aggressive, terminal form of multiple sclerosis. When they were both found dead, it was widely reported that the two had died in a Romeo-and-Juliet-style suicide because he could not bear to live without her.

Unfortunately, the truth was very different. Harry had been prone to depression and had begun to abuse drugs, including those prescribed for his wife. Locals on the island had witnessed his sudden bouts of uncontrolled rage.

In January 2007, Harry Horse’s rage exploded for the final time. He drugged and stabbed his wheelchair-bound wife. Reports of her injuries stated that she had been stabbed 30–40 times and that Horse even had to get a new knife when the first one broke. After he murdered his wife, Horse killed himself.[9]

No one knows why Horse, who had appeared to be so devoted to his wife, suddenly lost control in such a violent and catastrophic way. Some believe that what may have begun as a suicide pact turned to murder when the drugs they had taken failed to work.

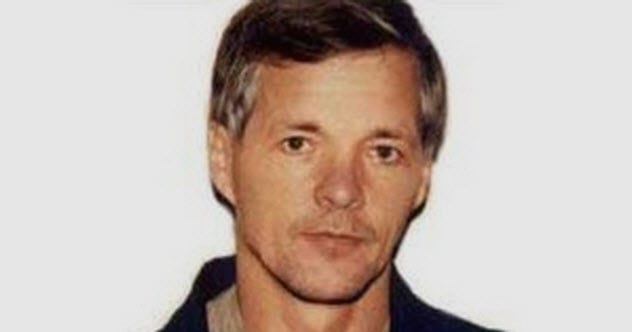

1 Krystian Bala

In December 2000, the body of a man washed up on the banks of a river in Poland. He had suffered repeated beatings, and his body bore a number of knife wounds. Forensic examinations showed that the man had been half-starved when he died.

He had also been bound with a single piece of rope in such a way that he would have been strangled by the cord around his neck if he had tried to free himself. These peculiar circumstances were not made public, and the murder remained unsolved.

A year after the case was shelved, it was discovered that Krystian Bala had somehow come into possession of the victim’s phone and had sold it over the Internet only three days after the man had disappeared and several weeks before the body was found. This brought Bala to the attention of police as a “person of interest” in the case.

When Bala published a novel, Amok, sometime later, their interest was piqued further. The novel had sold poorly, probably because of the extreme sexual violence and even bestiality. However, one section was of particular interest.

Bala had described the murder of a woman in great detail. The description bore an uncanny resemblance to the corpse of the businessman who had washed up on the shore. Even the peculiar method of tying up the victim was the same.

Further investigations showed that Bala had an intense interest in the progress of the police investigation, even checking websites about the crime at regular intervals. Police searched Bala’s home and found a number of items belonging to the victim. Most damning of all, they discovered that the businessman had been dating Bala’s former wife prior to his disappearance.

This circumstantial evidence—and even the confession which was later retracted—might not have been enough to secure a conviction. But Bala felt compelled to relive the experience in writing and then was foolhardy enough to publish it. Ultimately, he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the murder.[10]

Ward Hazell is a writer who travels and an occasional travel writer.

Read more fascinating stories about criminal writers on 10 Lifelong Criminals Who Became Successful Authors and 10 Strange Books Written By Serial Killers.