Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Gruesome And Shocking Facts About Victorian Surgery

We really don’t realize how lucky we are until we take a look back at the medical history books and recognize that most surgical practices during the Victorian era (1837–1901) were basically medieval. Between the 1840s and the mid-1890s, there were some radical changes in the operating room which went on to become a surgical revolution. However, many patients had to suffer up until that point.

The high mortality rate during this time is widely reported in newspapers, medical journals, and coroners’ inquests; even the healthiest of people wouldn’t make it out of surgery alive. It really was a tough time being a Victorian who needed surgery, but thanks to advances in modern science, these real-life horror stories are all a thing of the past. These following gruesome and shocking facts are not for the fainthearted.

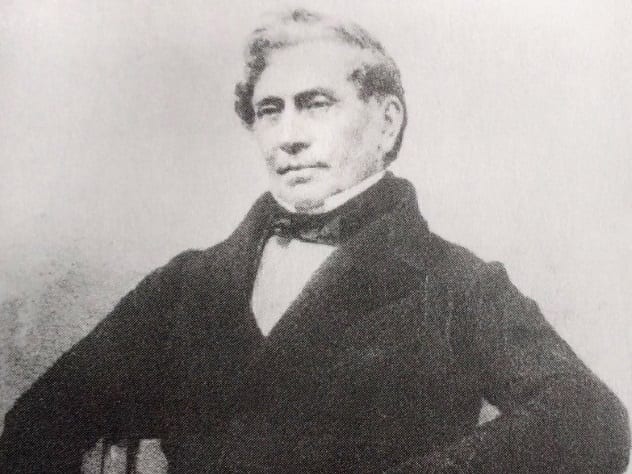

10 Chloroform Was Considered A Practical Anesthetic

The idea of surgery without anesthesia is unimaginable, but that was a grim reality in the past. In 1847, chloroform was introduced in Britain and used for the next 50 years. Scottish obstetrician Sir James Simpson was the first to try chloroform, and after passing out in his dining room, he realized that he could utilize its powerful fumes for practical purposes.[1]

Simpson invented a mask that would be saturated in chloroform and then placed over the patient’s face. After only a few minutes of preparation, surgery would begin. Even Queen Victoria herself was given chloroform for the birth of her last two children. Use of chloroform as an anesthetic eventually declined.

9 Hot Irons Were Used To Stop Bleeding

In Victorian surgery, where there was profuse bleeding from a wound, a hot iron might be used to stop the blood flow. Obviously, this was not pleasant at all, and alternatives to cauterization had been found long before the Victorian era. The scientific journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society reported on one such alternative way back in the 1670s. Surprisingly, they even recorded the surgery as a “cheerful” experience for the patient.

The report reads:

The leg therefore of the poor woman being cut off, immediately the Arteries were dressed with some linen pedlgets dipt in the [mysterious] Astringent liquor with a compress on it, and a bandage keeping all close against the arteries. The success was, that the blood was staunch without any other dressing; and instead of complaining, as those are wont to do who have a limb cut off, and the mouths of whose arteries are burnt with a hot Iron or a caustique to stop the blood, this Patient look’d very cheerful, and was free from pain, and slept two hours after, and also the night following; and from that time hath found herself still better and better without any return of bleeding, or any ill accident.[2]

8 Many Of The Surgeries Resulted In Fatalities

Surgery in the Victorian era was lethal, but not due to the fast-handed surgeons. Instead, it was the high probability of infection after the patient left the operating table. According to medical historian Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris, “[Surgeons] never washed their instruments or their hands. The operating tables themselves were rarely washed down. These places became a sort of slow-moving execution for the patient because they would develop these postoperative infections that would kill them, sometimes within days, sometimes within months.”[3]

Despite the pungent smell, doctors also believed that pus emitting from a post-surgery wound was a sign that things were healing well rather than what it really was—the result of a bacterial infection. The high death rate was just put down to “ward fever.” It wasn’t until surgeon Joseph Lister (1827–1912) introduced antiseptic practice and sterile environments in hospitals that the infection rate began to lower. Lister is now known as the “father of antiseptic surgery.”

7 Barbers Were Recruited As Surgeons During War

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 to the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, there was a brief period of calm in Britain. During the battle days, however, barbers did a lot more than cut hair—they were enlisted as surgeons and expected to perform operations on wounded soldiers. Despite no extensive knowledge or formal training that extended further than that of an apprentice, a barber-surgeon would be tasked with pulling teeth, bloodletting, and performing basic surgical tasks.

Surgeons and barbers were separated as two professions well before the Victorian era,[4] but patients in need of surgery would still sometimes approach barbers, as they had the sharp tools required for the job. Even in modern times, the red and white poles outside of a barber’s shop are a symbol of the blood-soaked napkins they used during bloodletting.

6 Leeches Would Be Used To Extract Blood

If the thought of blood-sucking leeches is enough to make your skin crawl, then this part might make you shudder. The heart pumps 5 liters (1.3 gal) of blood around the body in just one minute, and severe blood loss can lead to shock or even death. Luckily, our body has a clotting system in place to prevent this. However, during the Victorian era, the ancient practice of bloodletting hadn’t quite died out just yet.

Victorian surgeons would use live leeches to suck the blood from the patient. The practice of bloodletting was harmful, as it could cause anemia, but doctors overlooked this for thousands of years.[5]

5 Amputated Limbs Would Be Dropped In Sawdust

Imagine having your leg sawed off because of a broken bone or a fracture; then that limb is dropped in a bucket of sawdust by your side as you lie on the operating table, and people observing start to applaud. As mentioned previously, this could all occur without anesthetics, so it’s no surprise that patients would hope for an efficient and quick surgeon.

Dr. Robert Liston (1794–1847) was one of the most famous surgeons in history and was known as the “fastest knife in the West End.” He amputated his patients’ limbs with great speed and often called out during the surgeries, “Time me, Gentlemen! Time me!” On average, only one of every ten of Liston’s patients died at London’s University College Hospital, which was considered a great success, as other surgeons lost one in every four on average. Patients would camp outside his waiting room in hopes that he would consider them for surgery.[6]

4 Hospitals Were Only For The Poor

If you were lucky enough to be rich during the Victorian era, a family doctor would treat you at home from the comfort of your own bed. The poor would be hospitalized, and it was it was the role of the government, not the medical staff, to decide who would be admitted. Only one day a week was put aside for accepting new patients, and they would typically fall into two categories: either “incurables” for infectious diseases or “lunatics” who suffered from mental illnesses. Starting in 1752, the rule at St Thomas’ Hospital in London was that “no patient was to be admitted more than once with the same disease.”[7]

Operating rooms would always be situated on the top floor of hospitals to take advantage of the sunlight that would beam through a window in the roof. If patients were too poor to pay for their treatment, spectators were invited to view the procedures. For others, they would have to seek financial support from their parish or a willing patron.

3 Surgeons Wore Their Blood-Soaked Clothes With Pride

British surgeon Sir Berkeley Moynihan (1865–1936), recalled how his fellow surgeons would turn up to work, enter the operating theater, and put on old surgical frocks that were “stiff with dried blood and pus.”[8] Victorian surgeons were known for wearing their blood-soaked garments with pride, and they also carried with them the stench of rotting flesh as they made their way home.

Being a surgeon was not considered the noble profession it is today, and the hospital bug-catcher, who had the job of ridding the mattresses of lice, was paid more than a surgeon during this time. Due to high mortality rates, hospitals were known more as “houses of death” than houses of healing.

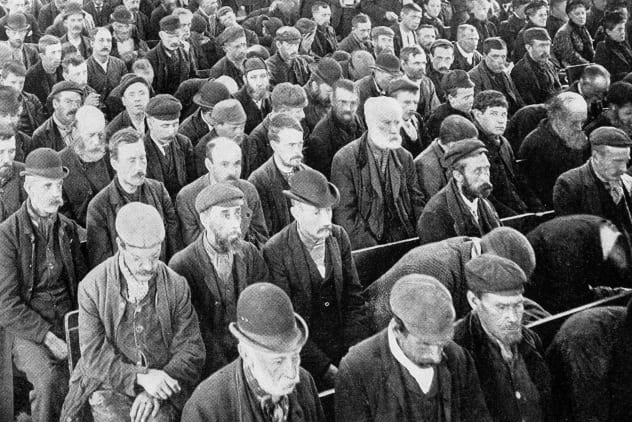

2 There Were Crowds Gathered Around The Operating Table

While patients would squirm on the operating tables and even attempt to run away during the painful procedures, onlookers would be there to enjoy the whole show. Operating in front of an audience was nothing unusual during the Victorian era, and the risk of germs entering the theater wasn’t even thought about.

Historian Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine, writes, “The first two rows were occupied by the other dressers, and behind a second partition stood the pupils, packed like herrings in a barrel, but not so quiet, as those behind them were continually pressing on those before and were continually struggling to relieve themselves of it, and had not infrequently to be got out exhausted. There was also a continual calling out of “Heads, Heads” to those about the table whose heads interfered with the sightseers.”[9]

The painful cries of the patients and the loud crowd watching the surgery could be overheard from the street many floors below.

1 One Of The Most Renowned Surgeons Was Transgender

In 1865, surgeon Dr. James Barry died. His gravestone reads: “Dr James Barry, Inspector General of Hospitals.” Considered one of the most successful surgeons in Victorian history, Barry was actually born Margaret Ann Bulkley and had no way of fulfilling his dreams in the operating theater, as women were denied a formal education. He enlisted in the army, and in 1826, he carried out a successful caesarean section in Cape Town, seven years before the operation was performed for the first time in Britain.

Known for his bad temper, he angered Florence Nightingale, and following his death, she said, “After he was dead, I was told that [Barry] was a woman. I should say that [Barry] was the most hardened creature I ever met.”[10] It wasn’t until a domestic member of staff cleaned his body after his death that the truth was realized. His gravestone was already listed and remains unchanged.

Cheish Merryweather is a true crime and oddities fanatic. Founder of Crime Viral and can be found on Twitter @TheCheish.

Read about more ways the Victorian era could kill you on 10 Ridiculous Things The Victorians Did In The Name Of Science and 10 Dangerous Beauty Trends From The Victorian Era.