Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Medieval Recipes Eaten By Kings That You Can Try At Home

We tend to think of medieval food as bland or boring. After all, there were no chocolates, potatoes, or tomatoes. (They all came from America.) But some medieval foods were so strongly flavored that we would find them unpalatable today, especially because people back then loved to mix fragrances like rose water or lavender with their dinners.

In medieval times, the very best food was eaten by the king and his court. And no king was more lavish than Richard II, who was known across Europe for his opulence.

So we are lucky that a recipe book written by his best chefs has survived to the modern day, containing no fewer than 196 recipes. It is called The Forme of Cury, and you can read it for free at Project Gutenberg if you can get your head around Middle English.

Let’s dig in.

10 Funges

This recipe—No. 10 in The Forme of Cury—simply calls for funges (the medieval word for “mushrooms“) and leeks to be cut up small and added to a broth, with saffron for coloring. Easy.

However, it also asks us to add “powder fort.” This was a well-known spice mixture in medieval times, much like garam masala is today. Powder fort was usually made from pepper and either ginger or cinnamon.

However, as this food was made for the king, they probably used a more complex mix, likely including cloves or saffron. For a powder fort mix you can try at home, combine 28 grams (1 oz) of cinnamon, 28 grams (1 oz) of ginger, 28 grams (1 oz) of black pepper, 7 grams (0.25 oz) of saffron, and 3.5 grams (0.125 oz) of cloves.[1]

Pepper was the most common spice in medieval Europe, followed by cinnamon, ginger, and cloves. Mushrooms were cheap and widespread in medieval England. So this dish would have been quite affordable but still well outside the reach of most medieval people.

9 Cormarye

Sometimes, kings needed to impress their guests, and the best way to do that was to serve them a big hunk of pork in a rich sauce. Cormarye, which is Recipe No. 53 in The Forme of Cury, would have been the main feature of a royal feast. The red wine and pork loin joint made it an expensive recipe even by modern standards, and the exotic coriander and caraway spices would have cost a fortune back then.[2]

Make a sauce from red wine, ground pepper, garlic, coriander, caraway, and salt. Roast the pork joint in it. Then add the sauce and the drippings to a broth and serve them together.

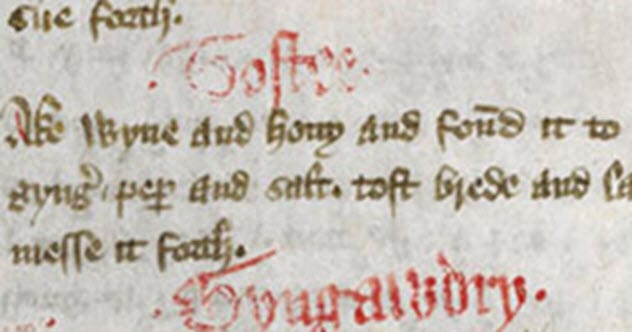

8 Toastie

Yes, you read that right. Richard II’s personal cookbook contains a recipe for a toastie—or tostee, as they called it. If someone served us this in a cafe nowadays, however, we might wonder if they’d made a mistake.[3]

This recipe, which is No. 93 in The Forme of Cury, is more like jam on toast than a modern-day toastie. Mix together red wine and honey in a saucepan. Add ground ginger, salt, and pepper. Cook it until it’s thick, and then spoon it over toasted bread. Chop up some fresh ginger and sprinkle it over the top.

7 Payn Ragoun

If you’ve ever wondered what medieval candy tasted like, this is it. Payn ragoun is essentially a medieval-style fudge, though they would have served it alongside meat or fish rather than as a snack or dessert.

You can find a modern version of the recipe here.[4] But to paraphrase: Mix some honey, sugar, and water together, and simmer over a low heat. Then add ground ginger.

The recipe actually calls for the cook to dip his finger in it. If it hangs when it drips back down, it’s ready. Add pine nuts, and stir until it thickens. Then leave the mixture to harden, and cool in a bread or cupcake mold.

6 Poached Eggs

The medieval method of cooking poached eggs—or pochee, as they called them—was almost exactly the same as it is today. “Take Ayrenn and breke hem in scaldyng hoot water.” Translation: Take eggs and break them into scalding hot water.

These medieval poached eggs wouldn’t have been served on toast for breakfast, though. They were much more likely to have been cooked en masse and served at a banquet on a plate alongside a specially prepared sauce.

This No. 90 recipe in The Forme of Cury has an accompanying sauce, though it is unlike any we’d make today. Whisk together two egg yolks, sugar, saffron, ginger, and salt. Add milk, and cook until it thickens, not letting it boil. Then serve. Find a modern translation of the recipe here.[5]

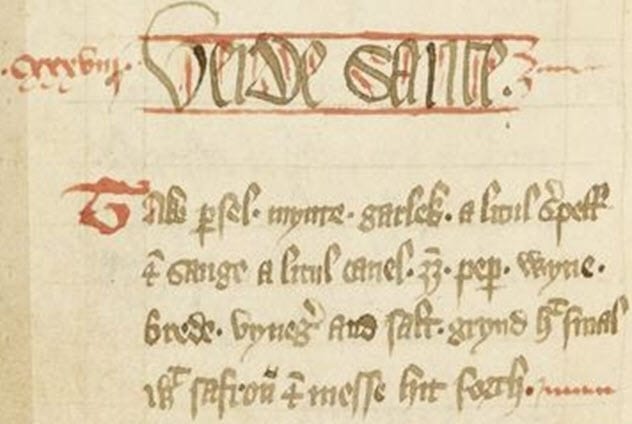

5 Verde Sawse

We all know salsa verde as a key component of modern Mediterranean cuisine. It seems that Richard II was also a fan of this popular sauce because The Forme of Cury contains a recipe especially dedicated to it—Recipe No. 140.[6]

This medieval version of salsa verde calls for parsley, mint, garlic, thyme, sage, cinnamon, ginger, pepper, wine, breadcrumbs, vinegar, and salt to be mixed together and served as is.

4 Crepes

It seems that crepes were a popular medieval sweet food. They are mentioned in Chaucer’s writings as “crips” and in Recipe No. 162 of The Forme of Cury as cryspes. Medieval French crepes were the closest to what we think of as crepes today, but cakes called crepes also existed in England and Italy.

A French recipe for crepes from 1393 can be found here.[7] The English version was a dough made of flour and egg whites which was rolled in sugar once it was cooled. The end result was more like a doughnut or powdered cake.

3 Compost

Recipe No. 100 of The Forme of Cury is called compost, though it had a different meaning back then. Short for “composition,” this was the medieval equivalent of throwing all your leftover vegetables in a Crock-Pot and leaving them to simmer. This was probably the closest that royal cuisine got to peasant food but with a much richer sauce.[8]

This particular recipe called for parsley roots, carrots, parsnips, turnips, radishes, cabbage, and pears to be diced and boiled until soft. Then they were sprinkled with salt and allowed to cool before being put in a large bowl with pepper, saffron, and vinegar.

The cook would then boil wine and honey in a saucepan and simmer for a while before adding currants and spices. This was poured over the vegetables, and then the entire dish was served.

2 Payn Fondew

Bread pudding is a dessert that is commonly eaten in the United Kingdom today. Most people know that it’s old, but few know that it actually dates from medieval times. Recipe No. 59 for payn fondew is effectively an early version of bread pudding.

Fry some bread in grease or oil. Mix egg whites in red wine. Add raisins, honey, sugar, cinnamon, ginger, and cloves, and simmer until it thickens. Then break up the bread, add it to the syrup, and let the bread soak up the syrup. Sprinkle with coriander and sugar.[9]

Nice to know the modern craving for sugar isn’t quite so modern, right?

1 Almond Milk Rice

Medieval people loved to cook with almonds. Many recipes in The Forme of Cury contain them, so it should be no surprise that they also enjoyed almond milk. The rice in this recipe would have come from the other side of the world, so only the richest could afford to make this recipe.

This was basically a medieval rice pudding, and you can find a recipe for it here.[10] Cook the rice, drain it, and place it in a saucepan. Then cover it with almond milk, and simmer for a while. Add honey and sugar, cook until the whole mixture thickens, and voila! Medieval rice pudding.

Read more about ancient foods you can still eat today on 10 Ancient Recipes You Can Try Today and 10 Of The Most Interesting Ancient Foods.