Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Eccentric Ways To Obtain A Medal Of Honor

As we’ve covered elsewhere, the Medal of Honor is the United States’ most prestigious award for bravery in combat. Naturally, most medal recipients’ stories are pretty straightforward: They involve a tough soldier, overwhelming odds in combat, and often the loss of life or limb. Yet there are more than a few outliers.

Some are secretive, some are shameful, and some are downright silly. If you’re looking for an oddball method of getting a Medal of Honor—a method that’s worked at least once—you could always try . . .

10 Writing In To Ask For One

Normally, an American soldier has to be recommended for the medal by either a member of Congress or a superior officer in his or her unit. You can’t self-nominate. This ensures that the Medal of Honor is given for brave conduct that others can confirm and protects its integrity from self-serving individuals. But back in the 1800s, the rules were a lot more flexible—so flexible that the government might as well have placed an ad saying medals were available upon request, “while supplies last.”

Asa Bird Gardiner was a Civil War veteran from New York who served as a company officer in a state militia unit. His unit was called into action a few times, and he received minor wounds while a company officer. This service was good, though by no means spectacular. But, evidently, he had heard something about the Medal of Honor, because a few years afterward, he sent a politely worded letter to the War Department to see if they’d give him one: “I understand there are a number of bronze medals for distribution to soldiers of the late War, and request I be allowed one as a souvenir of memorable times past.” Apparently his politeness was extremely persuasive, because they sent him one![1]

The rules have become more stringent since that time, and Gardiner’s medal was one of those rescinded by an audit in 1916 (more on that below). Nowadays, the process is much more formal, and the medal is generally not regarded as a mere memorabilia item. Still, it seems there’s no harm in asking.

9 Fighting A Secret Battle Against An American Ally

Since the Medal of Honor is intended as a decoration for courage in combat, it’s natural to assume it will be received for combat with America’s enemies. Most are. But Commander William McGonagle received it for an accidental conflict with the forces of America’s ally, Israel.

It was hardly his fault. In command of the USS Liberty in 1967, he was tasked with gathering naval intelligence. The problem was that, during his cruise, the Six-Day War erupted between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Though the US remained officially neutral in the conflict, the Israelis were responding to threats with extreme prejudice. After an error misidentified the Liberty as an Egyptian warship, Israel’s jets and torpedo boats were inbound.

It was a friendly fire incident on a grand scale. For almost an hour, the attackers pounded the ship, while the astonished Americans scrambled to protect the vessel. McGonagle was badly wounded in the initial onslaught, which shredded the ship’s bridge. Nevertheless, he refused to leave his post. He tried mightily to open communications with the Israelis while directing damage control efforts. When he finally did yield command 17 hours later, the ship was grievously scarred, and 34 crew members were dead. The Liberty still floated, however, due to the tireless efforts of its crew and commander. McGonagle refused medical treatment until the other seriously wounded personnel had been seen to.[2]

The horrified Israelis apologized afterward, and the US government acknowledged it had been a tragic mistake. But how could the government honor McGonagle’s bravery, and by extension that of the whole crew? They’d acted courageously. Yet no one wanted to further publicize the embarrassing incident.

In a compromise, the Medal of Honor was presented to McGonagle in secret at the Washington Navy Yard. Even his citation conspicuously fails to identify the forces attacking the ship during the events. His medal remains the only one to date presented in deliberate secrecy (as far as we know). It serves as at least a modest requiem for the sailors of the Liberty.

8 Participating In A Native American Massacre

US Army troops fought plenty of battles against Native Americans, and some of these could even be called fair fights. The so-called Battle of Wounded Knee was not one of them. It involved the US 7th Cavalry—George Custer’s old regiment—letting loose on a group of natives they were escorting.

The Lakota Sioux were being returned to their reservation at Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Ominously for the members of the band, the troops had been ordered to disarm them by force if necessary—all the while backed up by a battery of four cannons. All it took was a scuffle over a rifle, and some itchy trigger fingers, to light the spark.

Midway through the disarming process, both sides started shooting. Some of the Sioux rearmed themselves, but they were outnumbered and outgunned. The casualty figures speak for themselves: On the US side, 64 men were killed or wounded, some by friendly fire. By contrast, between 150 and 300 Lakota lay dead, many of them noncombatant women and children.

Twenty Medals of Honor were awarded among the 490 US Army participants, or four percent of all the soldiers present. As of this writing, this is the same number of medals given to US servicemen for actions in the 17 years of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan. Ever since the Wounded Knee awards, some have called for them to be retroactively canceled.[3]

On one hand, these soldiers may have acted with authentic physical bravery in a fight—saving the wounded, risking their lives on behalf of others, etc. But on the other, honoring them in this fashion (especially with such an astronomically high award rate) seems to grant the whole affair an honor it does not deserve. Currently, Congress has split the difference by leaving the medals alone and approving the placement of a national memorial at Wounded Knee. The monument, as yet, remains unbuilt.

7 Getting Killed Anonymously In An Ally’s Uniform

In one sense, any Medal of Honor is intended as a way of honoring the specific actions of the recipient. In another, the award serves as a symbolic representation of the bravery America asks all its soldiers to aspire to. Sometimes, the symbolism grows larger than individual deeds—no more so than in the case of the Unknowns.

Soldiers’ dog tags, serial numbers, and other identifiers—let alone DNA testing—are quite recent developments. In prior eras, it was quite common for dead soldiers to be buried in a nameless grave, especially if they fell in a large or chaotic engagement. World War I’s battles were the largest and most chaotic in history up to that time and produced a frightful number of anonymous corpses. To figuratively honor the sacrifice of all, several countries designated a representative unknown soldier, to be laid to rest with special ceremony.

Several US allies from that war dedicated tombs to their Unknown Soldiers, as did the US itself. To honor not only anonymous sacrifice but anonymous bravery, American authorities decided to symbolically award the Medal of Honor to five allied Unknowns: those from the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Romania, and Italy. All those involved agreed to ignore the usual requirement that recipients be US military personnel, as a special exception.[4] Each allied nation awarded a medal to the American Unknown in turn.

Since these medals stand for the bravery of all unidentified allied war dead, counting them all up together would swell the total number of Medal of Honor recipients by several orders of magnitude. Nonetheless, the awards serve as acknowledgment that even the authorities do not always have a perfect sense of what happens on the battlefield and that heroism occurs even when no one is around to record it.

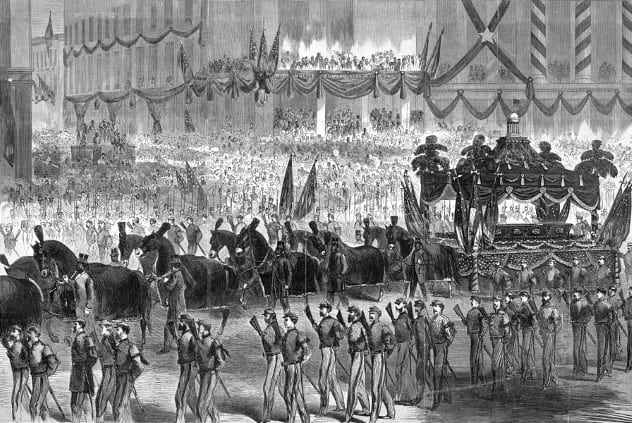

6 Guarding Abraham Lincoln’s Casket

The Medal of Honor was first created during the American Civil War; as often happens, its initial standards were rather ill-defined. The US military did not have much else to offer in the way of official recognition, so any sort of meritorious service might be considered to make one eligible for the award. That meant a number of awards which would not pass muster today.

In 1865, the United States was in mourning for its first assassinated president. Struck down at the close of an exhausting but victorious war, Abraham Lincoln was showered with as much ceremony as the country could possibly provide. He lay in state in the nation’s capital; his funeral train stopped in 12 cities along the way to his hometown of Springfield, Illinois; and a grand burial ceremony was held there.

Throughout the three weeks of pageantry, soldiers stood by the coffin, a final honor guard for the president. Most were veterans of many hard-fought battles, glad to serve in this last salute to their commander in chief. None were seeking accolades. Yet, after the president was buried, some of the nation’s grateful outpouring of recognition rubbed off on them. Twenty-nine members of the funeral guard were given the medal—even more than the number awarded for the affair at Wounded Knee described above.

Guarding a beloved president’s remains was certainly admirable service. Yet this hardly reaches the high bar for combat valor that the medal represents; for this reason, the 1916 review board rescinded all 29 of the funeral guard medals.[5] More than anything else, the whole business points to the need for a hierarchy of honors—since the existence of lesser recognitions preserves the highest honors for the most meritorious service.

5 Being An Extremely Plucky 11-Year-Old

The funeral guards described above were not the only Medal of Honor recipients with a connection to Abraham Lincoln.

In the days before electronic or radio communications, often, the best way to communicate on a battlefield was through the loud, sharp intonations of a drum or bugle. Since one hardly has to be a grown man to play an instrument, these combat music duties often went to the under-18 set. Thousands of young boys served in the American armed forces during the 19th century.

During the Civil War engagement known as the Seven Days Battles, the US army was reeling under the hammer blows of a resurgent enemy force. The army commander, spooked by the unexpected ferocity, fell back in a week-long fighting retreat. Union forces became steadily more demoralized, and often disorganized, over the course of the withdrawal. Some soldiers even abandoned their equipment—neutralizing their effectiveness—in order to speed their escape.

Not so for Willie Johnston of Vermont. He was a drummer, and knew he was a vital link in battlefield communication. It would have been easy for an 11-year-old to fall out of line and be forgotten or to flee rather than remaining with his fighting unit. But Willie remained resolute. He stayed with his regiment through it all—through days of confused marching and countermarching, nights of fearful redeployments, and a brutal, disorganized fight at the Battle of Savage’s Station, in which his unit suffered terrible casualties. By the end of it all, he was the only drummer in the entire division who had kept hold of his drum.

After the army had reached safety, a morale-boosting divisional review was set for July 4, and the commanding general picked young Willie to play for the whole division, in recognition of the boy’s service. The same general included the boy’s name in his report. When the story reached President Lincoln, he suggested the boy receive a medal for his valor, perhaps moved by memories of his own 11-year-old son, another Willie, who had died a few months before.[6]

The president’s suggestion was acted upon, and the following year, Willie got his medal. The boy was one of the first to ever receive it—and, to date, remains the youngest.

4 Getting Twice The Credit For A Single Act Of Bravery

Most consumers are familiar with “Buy one, get one free” deals; it’s often a simple matter to get two items for the price of one. Usually, this goes for modest items. But five men in World War I, by paying the price of a single day’s heroism, got two Medals of Honor in the deal.

First, at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry, Ernest Janson drove off a German counterattack using only his bayonet. The subsequent Battle of Soissons was a banner day for immigrants in US service. Louis Cukela, a Croatian, single-handedly wiped out two German machine gun crews with bayonets and hand grenades; Matej Kocak, a Slovakian, drove off another machine gun crew and also mustered disorganized French soldiers for an assault. At Blanc Mont Ridge, three months later, John J. Kelly ran out in front of the American advance, through an artillery barrage, destroyed an enemy machine gun nest, and herded eight prisoners back through the artillery fire. In the same fight, John Pruitt upped the total by capturing two machine guns and 40 enemy soldiers, all by himself.[7]

All of these were brave deeds. But why did they receive double credit?

The answer: They were Marines. The Marines are a hybrid service branch, serving at the intersection between land and sea. In the US military, the Marine Corps is a part of the Navy but routinely fights on land, which is normally the realm of the Army. During World War I, battalions of Marines were assigned to the Army, since the Army was better-equipped to coordinate the massed troop movements required on the Western Front. And the Army and the Navy each have their own versions of the Medal of Honor.

Naturally, each branch of the service wanted to claim credit for the bravery of these men. The Army emphasized that the combat happened under its direction; the Navy stressed that the men were naval personnel. In the end, each branch issued a separate medal, with a separate citation, for the same gallantry.

Since 1919, regulations have stated that no more medals can be awarded twice for the same action. But these men’s medals remain on the books: a plethora of honor, ten medals among five men.

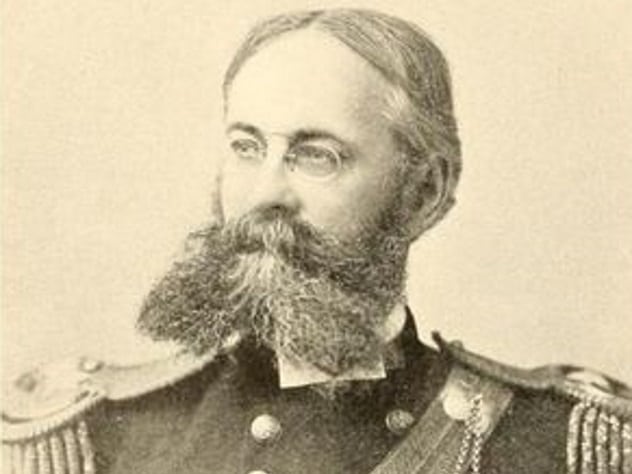

3 Making It A Lifetime Achievement Award

As the above case of the Lincoln funeral guard shows, it’s possible for a soldier to provide commendable service without rising to the level of Medal of Honor-worthy valor. For this reason, American military branches now offer various medals at assorted levels, using every synonym in the book (achievement, commendation, meritorious service, and so on). It’s possible to see these as gestures of admirable recognition—or, more cynically, as the military version of a participation award. Whatever one’s opinion, the divide becomes even greater when the award in question is supposed to be the nation’s highest.

It has happened twice. The first was for Frederick Gerber, an Army combat engineer. He served steadfastly in two wars (the Mexican-American War and the Civil War) and helped train numerous engineers in combat practices. The Army created the position of Sergeant Major of Engineers especially for him, and Gerber took pride in being the senior enlisted man of the Engineer Corps for seven years. He received his medal for “distinguished gallantry in many actions and in recognition of long, faithful, and meritorious services covering a period of 32 years” upon retirement.

The second was a general named Adolphus Greely. After solid Civil War service, he remained a lieutenant for 20 years. During this period, he commanded the disastrous Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (also called the Greely Expedition), a polar venture that saw 19 of its 25 men succumb to either the elements or cannibalism. Eventually promoted to Chief Signal Officer (a post carrying a general’s rank with it), he later supervised the laying of several major telegraph lines and coordinated relief after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. After reaching mandatory retirement age (64), he traveled home with a Medal of Honor in his baggage, the gift from Congress for “his life of splendid public service.” His medal was the last one bestowed for noncombat duty.[8]

2 Waiting 151 Years For Recognition

Some Medals of Honor are awarded quickly; this often depends upon commanding officers who have the ear of their superiors and can swiftly pass the recommendation up the chain. Others are awarded years or even decades later, after someone takes an interest in honoring a soldier for some remembered action. Modern regulations specify that a “chain of command” medal recommendation must be made within two years of the incident, while recommendations after that time limit expires must be approved by a special act of Congress. This system has sometimes resulted in gray-haired men receiving an award for service when they were young.

That said, few have had to wait for more than a century. Alonzo Cushing graduated from the US Military Academy in June 1861, just in time to race off to battle in the Civil War. He served with distinction for two years before heading to his last battlefield—Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. During the famous climax of that battle, Pickett’s Charge, Cushing was stationed in command of several cannons in the center of the Union line.[9] The charge came straight for him. After a punishing bombardment that killed his superior officers and severely wounded him, Cushing refused evacuation and continued to direct his men’s return fire. His guns helped turn back the assault; he died firing one final shot.

Cushing’s story was well-remembered; he even appears in a famous panoramic painting of the battle completed in 1883. Yet Medal of Honor recognition took three decades of determined effort on the part of a Wisconsin woman, who became interested in the story after purchasing the former Cushing farm. Finally, in 2014—151 years after the fact—President Barack Obama presented the award to Cushing’s closest living relative (a distant cousin who had taken weeks to track down).

“No matter how long it takes, it’s never too late to do the right thing,” Obama commented.

1 Sitting Around For Five Days

The Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 was a cauldron of terror and heroism for all its participants. One well-known story from the fight involves the men of the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment, which held a tenuous position with a ferocious bayonet charge after exhausting its ammunition. The unit lost one third of its men in the maelstrom, and two of the survivors (the colonel and the colorbearer) would receive the Medal of Honor for courage where the fighting was thickest.

By contrast, no less than 864 other men from Maine would receive the same medal for service rendered in the same period—during which they did precisely nothing.

The Gettysburg campaign was a major scare for the United States; rebel troops were penetrating deep into national territory, and every soldier possible was being mustered to stop them. Some of those were the men of the short-term 27th Maine regiment. Their enlistments were expiring, and they were due to go home at the height of the crisis. A member of Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet personally pleaded with the men to stay in Washington, DC, until the rebel invasion was defeated, promising Medals of Honor to each one who did. Most refused, but 311 men of the 27th Maine decided to stay. The rest packed their bags.

As it turned out, the 311 weren’t needed. They stayed in the defenses of Washington, performing light garrison duty, while the titanic battle raged in Pennsylvania. After the rebels were turned back, the 311 were released and sent home. They arrived in time to be mustered out alongside their brethren who had departed first.

But where does the 864 figure come from? The government official was true to his word and made sure the medals were awarded after the war. However, during the 1863 crisis, no one had kept notes on which 311 men stayed behind in Washington. Unable to determine who had been promised this outsized honor, the War Department threw up its hands and decided to award medals to every single man in the regiment, regardless of whether he performed the designated service or not.

In one of the most bizarre episodes in the history of the US Army, the government shipped 864 Medals of Honor to Maine en masse, directing that they be forwarded to the former commander of the regiment, Mark Wentworth. Wentworth did his best in the absurd situation, working to track down the men he remembered staying in Washington and give them their medal. Even so, he was left with more than 500 surplus medals (or about 14 percent of all Medals of Honor awarded by the United States between 1863 and 2018). Not knowing what else to do, he stuck them in his barn. After Wentworth died, the whole collection disappeared. Their whereabouts remain unknown.

As a postscript, the US military decided in 1916 to put together a review board that would audit all Medal of Honor awards given out up to that time.[10] The idea was to bring past actions up to higher standards for the medal, to avoid diluting its potency. It was an arduous task which required combing through mountains of records, but the board eventually finished the job. On their recommendation, 911 medals were struck from the rolls, and their holders were removed from the list of official recipients.

Some questionable ones remained, like the Wounded Knee massacre medals, or Adolphus Greely’s career recognition award, but the lion’s share of the rescinded medals were those belonging to the 27th Maine. All 864. The board agreed overwhelmingly that these were undeserved. In this way, the military demonstrated its willingness to enforce high standards for honoring valor, even if the gesture was long overdue.

David Ellrod lives in Maryland with his wife, three daughters, and one very excitable dog. He can be reached at https://twitter.com/DavidEllrod.

For more stories of military personnel operating in odd ways, check out 10 Soldiers Acting Like Grown-Up Children and 10 Unintentionally Hilarious Military Incidents.