Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Top 10 Crazy Facts About Psychiatry In The 19th Century

The treatment of the mentally ill has a notorious past filled with misunderstanding, torture, and theology. With the dawn of the 19th century, the path to comprehension began to be paved, ultimately leading to the psychology breakthroughs of Sigmund Freud, and the study of neurology. This is not to discount the terrible therapies the poor souls had to endure but to take a closer look at how the 19th century leads us to where we are today, and to highlight those few who really tried to help the mentally ill.

10Moral Treatment

The period of Enlightenment changed how scientists, philosophers, and society looked at the world. Psychiatry faced this new enlightened look, and moral treatment came out of it. This treatment was a moral disciplinary approach to those with mental illness instead of using chains and abuse.

According to Dr. James W Trent of Gordon College, before moral treatment, people with psychiatric conditions were referred to as insane, and treated inhumanely. Philippe Pinel of France at Bicetre Hospital, in Paris, advocated for moral treatment of the mentally ill. In place of physical abuse, Pinel called for kindness and patience, which included recreation, walks, and pleasant conversation. Pinel made this change out of reading, observation, and reflection; rather than a result of accident or experiment.

Moral treatment began to spread around the world. In the United States, Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician, began to practice moral treatment. Rush saw one of the causes of mental disease as the hustle and bustle of modern life, so taking those inflicted away from those stresses could help restore their minds.

Rush did employ some of the methods of moral treatment; conversely, he also used bloodletting and invented the tranquilizer chair.[1] Pinel had high hopes for his new type of therapy, but there were still those who used tortuous techniques to restrain those they considered mad.

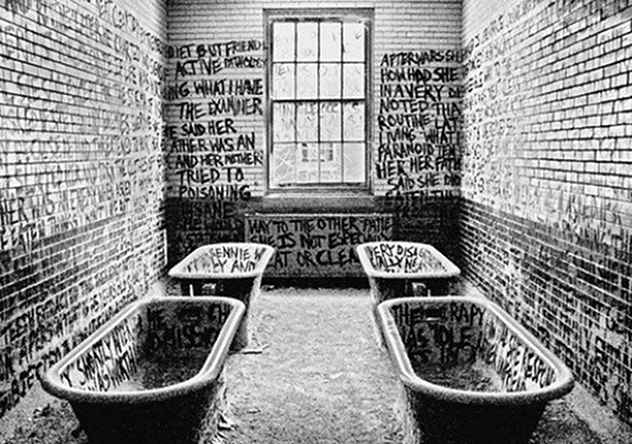

9Booming Asylums

We all have a terrible image of insane asylums, and a number of us have heard a ghost story or two surrounding these foreboding buildings. Often cared for by their families or housed in almshouses or jails, the number of people sent to asylums began to dramatically increase in the 19th century.

During the start of the century, cities became more populated, and mental illness shifted from being a spiritual punishment from God to a social issue. Communities responded by building more and more institutions, which were set up to handle the growing numbers.[2] For example, in England, the number of “patients climbed from 10,000 in 1800 to ten times that in 1900.”

Historians have agreed upon three main bodies of thought to try and answer why the numbers catapulted in one century. The first is due to modernization and increased stresses that came with it. The second is the population grew more and more intolerant of disruptive behavior. The third is the growing power given to physicians and alienists—or mad-doctors. Being able to look back, we can see it looks to be a combination of all three.

With the booming numbers of asylums, lurid tales of torture and abuse began to leak out from the ominous structures placed on the outside of cities and towns. The mad-doctors set up a number of classifications, given to try and make the asylum “cure” those with psychiatric conditions. For example, men had to be separated from women, the curable from the incurable, etc. Nevertheless, with the rules and best of intentions, asylums earned their infamous nickname, Bedlam, “a byword for man’s inhumanity to man.”

8Rise in Research

Going to university to study a specific subject, has grown to be a commonality these days. In the 19th century, the increase in asylums and new treatments created a rise in those wanting to research psychiatry, and answer the plaguing question of why some people went “mad.”

For example, Oxford-educated physician Thomas Willis, who coined the term neurology, strove to pinpoint the mental functions that coordinate with particular parts of the brain. Willis modeled the idea that the central and peripheral nervous system depended on the operations of animal spirits, or, chemical intermediaries between the mind and the body.

Another doctor about this time, Archibald Pitcairn, who taught at Leiden in the Netherlands, treated mentally ill patients and argued that they suffered from “false ideas induced by the chaotic activities of those volatile animal spirits; these, in turn, fed back into the muscles to produce confused and uncontrolled movements in the limbs.”[3]

Today, we know the brain does not contain animal spirits, and they do not cause mental illness; rather, it is chemical imbalances in the brain. For a time when X-ray was being discovered, and the only way to study the brain was to pull it out of a person’s skull, these doctors set the foundation for modern neurology and present-day treatments.

7Nervous Disorders

Today when someone suffers from a nervous disorder, they are referring to high blood pressure, heart problems, trouble breathing, etc.[4] Back in the 19th century, nervous disorders referred to shattered nerves, nervous collapse, nervous exhaustion, or a nervous breakdown. The symptoms did not include heart problems or trouble breathing; but instead, a sense of emptiness, hopelessness, obsessive thoughts, sluggishness, and a general indifference.

This is where we got the saying about having “strong” or “weak” nerves. The idea of nervous disorders being a “functional illness” that only affected the “superior” people came from the scientific emphases that ran rampant during this time.

On both sides of the Atlantic, Victorian men were wallowing in hypochondria and Victorian women falling into hysteria. Private “nerve” clinics to treat this malady sprang up, where the rich could go the spa to recover from their nervous breakdowns. These disorders only glamorized mental illness and took away from the real understanding of what those poor people had to endure.

6Monomania

The 19th century was full of scientists seeking to find reasons and answers for why the mentally ill became that way. Doctors commonly believed that insanity was a defect of reason, and the person’s inability to rationally comprehend reality.

With the rise in research and study of the mentally ill, Jean Etienne Esquirol brought another hypothesis to try and answer why: Monomania. This is partial delirium, where the patient suffered from a false perception, which they then pursue with logical reasonings. These false perceptions can be illusions, hallucinations, or false convictions. Monomania is not an absence of reason, but the presence of a false idea.

For example, mentally ill patients can suffer from illusions and hallucinations, and it is these that convince the patients of an incorrect reality, to which they act out logically to this false perception.

Esquirol developed the diagnosis of monomania to explain paranoia disorders; such as, kleptomania, nymphomania, and pyromania, which all can be detected by a trained eye.[5] Monomania provided the needed foundation for scientists and doctors to discover concepts such as obsession and psychopathy.

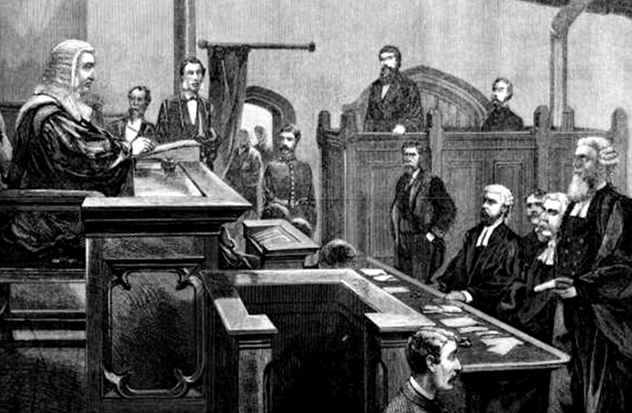

5The M’Naghten Rules

On January 20, 1843, a Scottish craftsman, Daniel M’Naghten, believed Tories and Conservatives were intent on murdering him for his involvement in the early workers’ movement in Great Britain. In response, M’Naghten set out to kill the sitting prime minister, Robert Peel.[6] However, mistaking Peel’s secretary, Edward Drummond, for the government leader, M’Naghten shot and ultimately killed Drummond.

During the trial, M’Naghten pleaded not-guilty due to “moral insanity” in the form of monomania. This tactic worked, and M’Naghten was found not-guilty by reason of insanity.

Outraged, Queen Victoria and the public demanded this case be reviewed. As a result, many questions were posed to all the judges regarding the case and verdict. The responses have become known as the M’Naghten Rules, and serve as the basis for “determining legal insanity throughout many parts of England and the United States to this very day.”

4The Opal, the Lunatic’s Literary Journal

The moral treatment movement started by Pinel in Paris, gave rise to the opportunity for the patients in New York’s Lunatic Asylum Utica, to create their own literary journal, The Opal.

The first issue, in 1850, was only given to members of the asylum; however, the next issues were sold at an asylum fair, so by 1851, the journal was being published in the American Journal of Insanity, the professional forum for that time. At the end of the first year, The Opal had over 900 subscribers and was in circulation with 330 periodicals, and all the profits went into the asylum’s library.

Moral treatment calls for kindness, patience, and recreation. The creation of The Opal demonstrates an essential element to this treatment: preventing sickness and sorrow.[7] Along with fairs, theatrical shows, debating societies, and lectures, The Opal aroused the mind of the insane away from morbid trains of thoughts and into the rational, orderly, polite facilities of the mind.

The journal was an important outlet for the patients, and it provided them a platform to showcase their own voices. However, The Opal only lasted until 1860, when it to “fell victim to the demise of the moral treatment movement.”

3India’s Insane Asylums

Historically, Great Britain has colonized numerous countries around the world; India was one of them, during the 19th century. As the number of the mentally ill grew in Europe and the United States, so did the numbers in India.

As the asylums began going up, the British Crown initiated the same treatment styles as Pinel and Esquirol for their Indian asylums. Even so, the local British colonials and authorities considered themselves superior to the locals, and they were unwilling to share facilities with them. Letting prejudice and bigotry take hold, the physicians separated the locals from the British. Those deemed “insane” in India were now sent to decrepit, public institutions.

The Superintendent, Surgeon R.F. Hutchinson, MD, of Patna Lunatic Asylum sent a report to the Inspector General, explaining the need for more space, and better sanitary conditions in one of these asylums. He explained that the population was already overcrowded at 138, and the number went up to 151 without larger buildings to accommodate the growing population. Hutchinson also stated that due to the drainage sending everything to low ground, where the Indian people reside, parts of buildings were unusable and unfit for occupation.

In his report, Hutchinson puts it rather bluntly when he states, “this evil cannot, of course, be remedied without either raising the plinth or removing the Asylum bodily to a higher site.”[8] Hutchinson was one man, struggling to care for his growing population of mentally ill, and instead of sitting back, he did what he could to try and make their life a bit better.

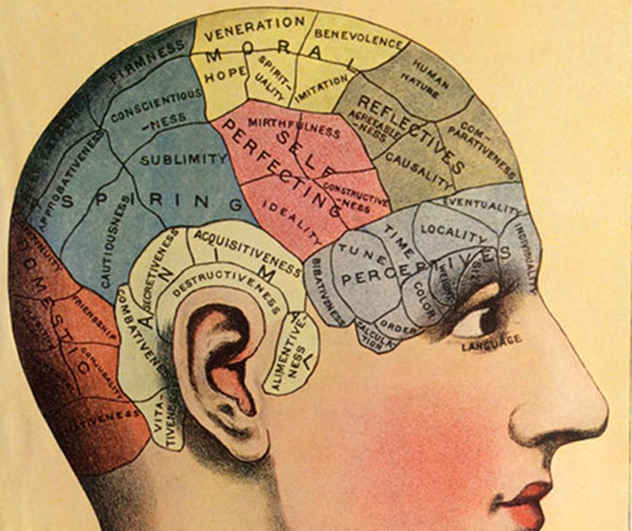

2Phrenology

Many us have seen the pictures with words written all over a human head. Some of us might even have one as a knick-knack; however, none of us will pull it off the shelf and use it to define how a perfect stranger will act. Back in the 19th century, this was a popular study known as Phrenology.

This is the study of the relationships between character and the shape of the skull. Austrian physician, Franz Joseph Gall, a founder of modern neurology, put Phrenology together and held the belief that the shape of the skull influences behavior.[9] Gall studied mathematicians, coachmen, sculptors, and the like searching for commonalities between the shapes of all their skulls.

However, Gall faced two significant problems with his theory. One, he based his claims on a single happenstance. For example, “cautiousness” was above the ears because he felt a large bump there on a cautious priest. Two, Gall only looked for cases that conformed to his hypothesis and simply ignored those that contradicted him.

Gall was way off when it came to Phrenology and how the brain actually works, yet he still laid the foundations for future neurologists to pick up and better understand the miraculous organ.

1Dorothea Dix

The 19th century brought about insane asylums, increased research, advanced treatments, and new studies of thought. While some of these provided good to those in need; nonetheless, numerous brought more misery to the mentally ill, than they did comfort.

An amazing lady, Dorothea Dix, saw the suffering of those in asylums, poorhouses, and jails, and sought to expose the cruelties of their confinement.[10] Taking her fight to Boston, Dix found powerful allies, including Rev. William Ellrey Channing, the leader of Unitarianism that sought for social reforms.

In 1841, Dix began traveling around Massachusetts, examining the conditions those with mental illness had to live in. She found them in “cages, closets, cellars, stalls pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience.”

By January 1843, Dix took her petition to the state and sought increase funding for these establishments. However, her’s was the only voice seeking sympathy and help for these people. But she did not give up, and eventually, the state passed legislation to expand the state insane asylum in Worcester.

Dix did not stop there. She went on to lobby for the better treatment of the mentally ill in many states. At a time when those deemed “insane” or “mad” were treated worse than animals, Dorothea Dix was their voice, and she fought for them.

Just a person who loves to write