Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Technological Advances That Animals Had First

It’s easy to forget that we rely on so many wonderful technological breakthroughs that were based on observations of raw nature. New inventions are always impressive, but just how new are they?

Animals probably think that we are a little late to the party. But never mind, let’s take a moment to appreciate the mutual benefits of evolved design. Here are 10 things you surely thought were all human. You’re about to find out that animals got there first.

10 Air Brakes

Have you ever looked out the window of an airplane just before landing and noticed small slats pop up along the wing? These slats are designed to prevent the airplane from stalling as it slows.

Birds have their own version of this clever technology in the form of specially adapted feathers. Bird feathers are broadly divided into primary and secondary feathers, with some being vital for flight and others more for display.

But there’s nothing impractical about the feathers on the part of the wing called the “alula” (the front edge of the wing where a bird’s “thumb” would naturally be).[1] These feathers can be adjusted by a bird to open up a small slot that helps to stabilize the bird and avoid a stall in slow flight or upon landing. Neat!

9 Sonar

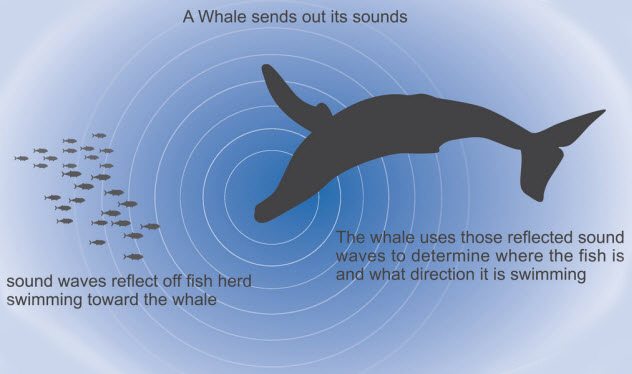

Ships, submarines, and seagoing devices are often equipped with sonar to navigate, avoid obstacles, and track down targets underwater. Sonar works by emitting a sound at a certain frequency, which spreads sound waves into the surroundings.

Ships, submarines, and seagoing devices are often equipped with sonar to navigate, avoid obstacles, and track down targets underwater. Sonar works by emitting a sound at a certain frequency, which spreads sound waves into the surroundings.

The sound waves rebound off solid objects and return to the sonar device that emitted them. The sonar device then collects information about the shape, size, and distance of the objects. This is particularly useful for the military, of course, but it was whales and dolphins that invented it first!

These amazing animals can discern differences between even very small objects from 15 meters (50 ft) away using their sonar skills alone. They don’t need an electronic device to broadcast their frequencies across the ocean. They’ve evolved to use their own voices and the receptors in their bodies to find their way around under the sea.

It is thought that the animals create a “soundscape” in their minds from the constant feedback, helping them build a map of their environment. They also use their sonar to locate food and friends.[2]

Military sonar is so similar to whale sonar that it even uses the same frequency: somewhere between 100 Hz and 500 Hz. Some people have speculated that this may be the cause of many mass strandings of dolphins and whales, as they may become confused between their own signals and that of the military devices.

The navy has tested their sonar up to 235 dB, while whales usually emit sonar signals at around 170 dB. It’s possible that the louder signals might disrupt the sea creatures’ sense of direction and guide them off course. Still, it’s impressive that something used by whales is so effective that humans haven’t found anything that works better.

8 Bioluminescence

Speaking of sea creatures, our underwater pals have used just about everything to enhance their survival. Long before humans invented glow sticks, glow-in-the-dark stickers, and night-lights, fish at the bottom of the ocean were glowing away for centuries.

Fireflies, glowworms, and even some types of fungi also use bioluminescence to their advantage. All these organisms have evolved to glow in the dark for reasons as diverse as attracting mates, luring prey toward them, warning predators away from them, and communicating with others of their species.[3]

Much research has been—and continues to be—invested in bioluminescence as a biotechnology with many potential applications in the modern world. The main chemical involved in this is luciferin, which has a short life span in its active state of light output. Various companies are working on this problem, with the possibility of streetlights and some types of medical procedures relying on bioluminescence in the future.

Bioluminescence is created by a simple chemical reaction that involves luciferin, an enzyme, and a few other cofactors specific to individual creatures and plants. Humans are only just catching up—but it’s never too late to learn!

7 Solar Power

Recently, a group of scientists were studying spotted salamanders and found that the embryos of these animals contained algae that live inside the baby salamanders before they hatch. The algae survive by eating the waste produced by the baby salamander embryos. In turn, the algae produce energy and nutrition for the developing babies.

These salamanders (which are amphibians, not reptiles like lizards) are essentially brought up via photosynthesis, the same process used by leaves on trees to convert sunlight into energy. It is also similar to how photovoltaic cells (solar panels) convert sunlight into electricity.[4]

6 UV Detection

Humans are subject to the effects of UV light all the time, but we can’t naturally see it. That’s why it’s so easy to get sunburn. These days, you can buy light detectors that “translate” UV waves into a form you can see.

Normally, we can’t see UV light because of the number of proteins in our eyes. What on Earth?

The structure of an animal’s eye is partly made up of proteins called opsins. Some animals have only one or two types of opsins in their eyes, so they see fewer colors and types of light waves than humans. In contrast, we have three types of opsins, allowing us to see a wide spectrum of color.

However, some animals, such as the chameleon, have more than three types of opsins in their eyes. So chameleons can see UV light rays in addition to the colors that humans see. There are likely many more details on plants, objects, and other animals that a chameleon will be able to appreciate that we cannot.

Chameleons do all that with their naked eyes, no devices required. There are many other reptiles, insects, birds, and water-dwelling creatures that may also see UV light.[5]

5 Farming

Farming may not seem like a technological advance, but it’s relatively new in terms of human history. When comparing the level of mass production and the amount of livestock, things look very different now than 50 years ago.

Farming may not seem like a technological advance, but it’s relatively new in terms of human history. When comparing the level of mass production and the amount of livestock, things look very different now than 50 years ago.

However, ants have been farming intensively for a lot longer than 50 years. They love to feed off the sticky, sugary secretions that aphids poop out after eating plants.

As a result, the ants go to great effort to ensure a continuous supply of this “honeydew” by preventing the aphids from moving too far from the ant colony. The ants will bite off the aphids’ wings and emit chemicals that retard the growth of these wings. Sneaky!

As if that wasn’t enough, ants were recently found to encircle groups of aphids with the ants’ chemical footprints, normally used to mark the territory of the ant colony. These footprints seem to make the aphids slow and unlikely to move from their spots, giving the ants reliable access to their favorite sugary food source.[6]

Just like the farm animals kept by humans, though, there is a benefit for the aphids. The chemical footprints evidently put off predators, such as ladybugs, from eating the aphids. So the enslaved aphids are at least protected from those big, scary, spotted bugs . . . thanks to the ants.

4 Soundproofing

If you’ve ever spent time in a soundproofed room, you might have enjoyed how peaceful it was. A combination of insulative layers, absorbent materials, and more create an atmosphere where little extraneous sound can be heard.

For generations, owls have been making use of these qualities for less peaceful reasons. To glide in and snatch their unsuspecting prey with deadly precision, owls must be completely silent because the rodents they eat have incredibly sensitive hearing.

For example, the feathers of the barn owl are so soft and fine that it cannot afford to hunt in wet weather as it would become waterlogged and cold. This is the trade-off for the owl’s perfectly soundproofed body, which is ideal for floating in the dark to within a few feet of a small mammal before dropping down to grasp it away in those sharp talons.[7] The only noise will be a squeak!

It’s the design of the feathers that achieve this. Tiny divides and fibers separate the flow of air through the wings. This prevents any “rasping” sounds, which are caused by air resistance, that are a feature of other birds’ flight.

3 Cloning

After the controversy over Dolly the sheep, you might have assumed that cloning was a new and strange phenomenon. If you want an alternative opinion, though, ask a starfish (aka sea star).

Starfish have been asexually reproducing with no difficulty well before cloning was even a word. Not only that, but starfish that clone themselves live longer and healthier lives than starfish that reproduce sexually.[8]

So cloning obviously suits these creatures rather well. Additionally, if a starfish breaks a limb or even breaks its body in half, the creature will simply regrow and regenerate itself as needed. Some species even have the ability to produce a new body from part of a severed limb.

Starfish are evidently the experts when it comes to cloning, so perhaps we ought to leave it to them?

2 GPS

The migration of birds is still a remarkable mystery to scientists. There are many possible explanations as to how birds know where to go—the position of the Sun, the use of a star map, their sense of smell, detection of the Earth’s magnetic field, or even the memory of landmarks from their previous journeys.[9]

But none of these seem to fully explain how birds can navigate so successfully and consistently to remote destinations, often under hostile conditions and sometimes having no prior experience with the routes. It’s as though they have some highly advanced GPS technology—that is far ahead of human capabilities—already built into their little bird brains.

The magnetic field theory seems most likely, as foxes have also been shown to align themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field to hunt. If other animals are savvy about magnetic fields, it seems only natural that birds would be, too. After all, it’s not so different from the compasses that humans use to navigate!

1 Retractable Blades

The humble domestic cat strikes again with a scratch of genius. Its claws can be released or sheathed at will, keeping the claws sharp and preventing the cat from injuring itself when using its paw to wash its face.[10] The claws can be drawn back into soft integral sockets in the cat’s paw, keeping them out of harm’s way.

Did this inspire all those intricate, retractable gadgets on your pocket penknife? It would be awesome to think that your house kitty sparked the idea for such an incredibly convenient tool and safety feature.

To me, it’s not the World Wide Web. It’s the weird, wacky, and wonderful. And that’s the way it should be. Inspire, explore, and enjoy the trip. That’s my philosophy and what I hope to teach others. Happy trails!

Read more incredible facts about animals’ superiority to man and how it helps us on 10 Amazing Ways Animals Are Superior To Man and Top 10 Secret Ways Animals Help Humans.