Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Wild Game Show Scandals Where Someone Got Scammed

Game shows appeal to our primal desires. At best, their prizes offer us an ability to put a down payment on a house or send our kids to college. At worst, you’ve beaten and bloodied a stranger for a Blu-ray box set of The Crown.

Either way, it’s a snatchy, gross business. No wonder it’s attracted so many scammers with so many different ways of cheating, although some have ultimately had to settle for the prize of a prison sentence.

10 Charles Ingram Almost Steals £1 Million On Who Wants To Be A Millionaire

In September 2001, Charles Ingram appeared on the UK version of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire. He did extraordinarily well, ultimately winning the top prize of a million pounds. Ingram rarely seemed confident. He erratically switched from one answer to another but always somehow landed on the right one.

As it turns out, he was being fed the answers by two accomplices: Tecwen Whittock, a college lecturer, and Diana Ingram, Charles’s wife. Whittock was sitting in the Fastest Finger First contestant section and would go on to have his own run at a million. Diana sat in the audience. She had previously won £32,000 on the show. The couple seems to have been obsessed with it.

Charles’s bumbling over the answers apologetically was actually part of the trio’s system for victory. It was Whittock’s or Diana’s job to cough at the appropriate moments to indicate to Charles which answer he should pick.

Show producers found the whole thing fishy enough to take it to court. There, a sound expert claimed that 192 coughs had been made during the recording and that 36 were likely made by Whittock.[1]

The trio received fines and suspended prison sentences. A year later, Charles Ingram declared bankruptcy.

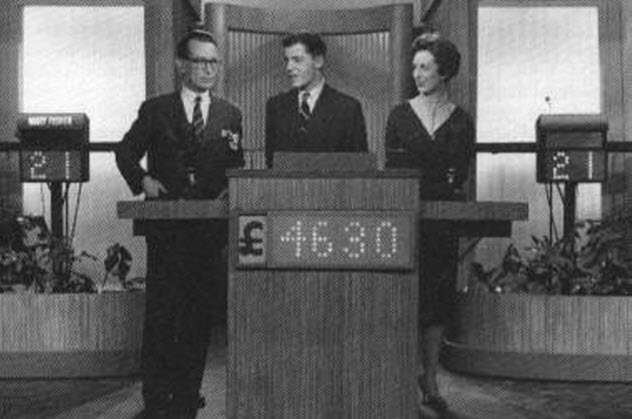

9 The Twenty One Scandal

In 1956, NBC launched a new quiz show called Twenty One. Contestants were pitted against each other head-to-head and tasked with answering general knowledge questions. The first player to answer 21 questions correctly was the winner.

It was designed to be a quiz for true trivia aficionados with genuinely difficult questions and a serious sporting tone. But it didn’t make for compelling viewing. In fact, Dan Enright, the show’s producer, described the initial broadcast this way: “A dismal failure. It was just plain dull.”

To make the show more interesting, the decision was made to simply rig it. That way, there would never be a dull contest. Also, Enright wanted characters that people could invest in. Some they could hate, some they could root for. The most important thing was that they were familiar faces whom people tuned in to see. It was therefore crucial that a star for the show was chosen and fed questions to ensure that he remained the show’s champion.

Herb Stempel was the first poster boy with a six-week streak of victories. At that point, Enright and his colleagues decided that they’d had enough of Stempel and decided to replace him with what they believed was a more marketable young academic named Charles Van Doren.

Stempel and Van Doren battled each other over several shows—each time ending in a rigged draw. The strategy proved to be a success, and audience interest steadily increased. People tuned in to see if the champion would finally be toppled. That happened on December 5, 1956, and Van Doren’s winning streak would not end until March 1957.[2]

The public’s love affair with the Twenty One champion came to a bitter end when mounting evidence from Stempel and other former contestants on the show made the truth undeniable. As a result, the show was canceled in 1958.

At the time of the scandal, no law existed that the producers of Twenty One were breaking. However, in 1960, as a result of the incident, the Communications Act of 1934 was amended to specifically prohibit the fixing of quiz shows.

8 The Dotto Scandal

At the time of Dotto’s cancellation in August 1958, it was the highest-rated daytime television show in history. It had only been on the air since January 1958, so it was a bit of a head-scratcher to the general public who wasn’t made aware that the show was fixed.

That didn’t last long. On August 28, the district attorney announced that he’d be investigating the suspicious circumstances of Dotto’s cancellation.

It turned out that the notebook of a contestant named Marie Winn had been found by a standby, Edward Hilgemeier Jr. It contained questions and answers to the show’s ongoing taping. Hilgemeier showed the pages to that night’s beaten contestant, leading producers to pay $4,000 to the loser and $1,500 to Hilgemeier to keep them quiet.[3]

But Hilgemeier eventually broke his silence, contacting the show’s sponsor, Colgate-Palmolive, who decided only a week later that the show needed to disappear completely.

7 UK Version Of Twenty One Also Rigged, Leading To Bad Prizes Being Offered For Decades

The 1950s was just a rotten time for game shows and Twenty One in particular. Not only was the American version proven to be fixed, the English one was, too.

In 1958, UK TV station ITV pulled Twenty One off the air after contestant Stanley Armstrong declared that he’d received “definite leads” to the answers. The tip-offs took the form of a set reading list for favored contestants.

Initial reaction was relatively mild. TV regulators simply decreed that a printed statement of quiz shows’ rules had to be made available from then on, including statements about the extent to which contestants were coached beforehand and the prizes they would receive.

However, the incident did foreshadow a monumental shift for British quiz shows a few years later when the Pilkington Report was published.[4] It suggested that the removal of large cash prizes would eliminate most interest in the shows as they were simply a celebration of greed in their current form. The report concluded that a cash cap for quiz show prizes of £1,000 would help clear up issues of morality.

The government agreed, and a cap remained in place until the mid-1990s. By the time of its abolition, the cap had been raised to the point where the UK version of The $64,000 Question was able to offer the marginally gluttonous prize of £6,400.

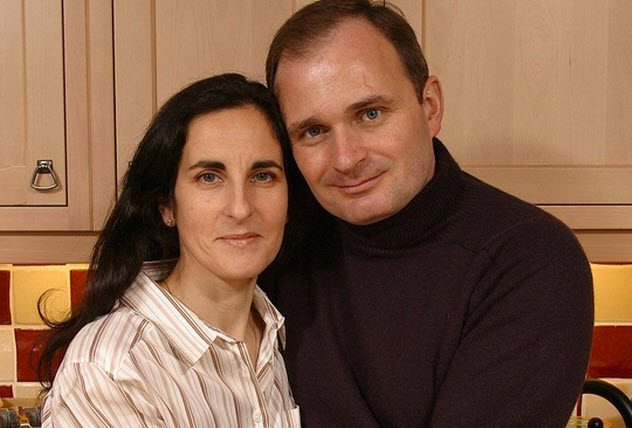

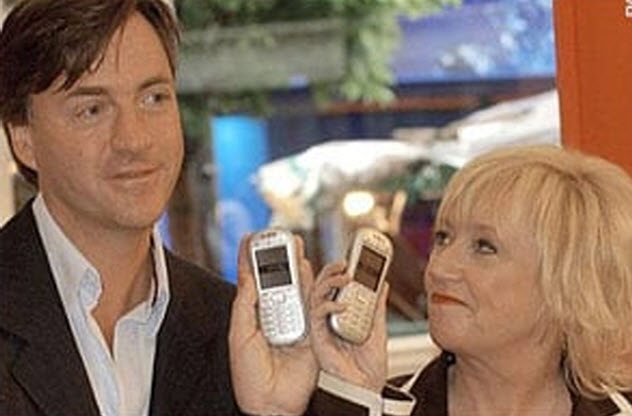

6 The ‘You Say We Pay’ Scandal On Richard & Judy

Richard Madeley and Judy Finnigan were the king and queen of light entertainment in the UK. Their eponymous early afternoon show, Richard & Judy, was a ratings hit for Channel 4, and thus their phone-in game show segment, “You Say We Pay,” attracted millions of callers.

It was essentially first come, first served as far as contestants went. So there was a certain point where all the slots were filled and no more callers could possibly be selected. However, instead of informing viewers and closing the phone lines, the hosts would routinely continue to encourage viewers at home to call in for their chance to win a big cash prize.

Richard and Judy successfully argued that they had no knowledge of the practice, and the blame was instead placed on Eckoh, the contracted operators of the phone-in. The Independent Committee for the Supervision of Standards of Telephone Information Services ended up fining them £150,000.

Over the show’s run, around five million people had called to take part in the quiz. The committee stated that around half had been unfairly charged the £1 call-in fee. As a result, Eckoh was ordered to pay around £1.5 million back to cheated members of the public.[5]

5 The $64,000 Question And The $64,000 Challenge Scandal

Reverend Charles “Stoney” Jackson Jr. first appeared on The $64,000 Question in the late 1950s. He was confused by his success almost immediately. Producer Mert Koplin had informally quizzed him before the show. Whenever Jackson couldn’t produce an answer to one of Koplin’s questions, it was given to him.

On his second appearance, Jackson was happy enough to continue the lucrative masquerade. Producers fed him questions that they believed he could answer until he had won $16,000. At that point, he was told that he could quit and collect his winnings or they’d give him a question he had no chance of knowing. Jackson took the money.[6]

Now firmly in the producer’s good graces, Jackson was invited back two months later to compete in the spin-off show The $64,000 Challenge. It pitted winners of over $8,000 on the main show against new competitors. Jackson won again, beating Doll Goosetree. Jackson later found out that Goosetree had been misled into believing that Shakespeare would be featured prominently.

Jackson’s crisis of conscience reached a boiling point, and he began contacting anyone who would listen. The New York Times and Time magazine weren’t interested in printing his story. The legitimacy of Jackson’s claims only became apparent when bundled with the concurrent Twenty One and Dotto scandals.

4 The ‘Hello Pappy’ Scandal On Wowowee

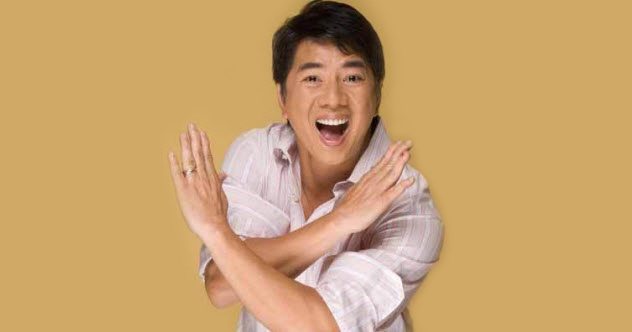

Willie “Pappy” Revillame was the host of light entertainment show Wowowee. It was largely built around a collection of mini games in which lucky contestants could win prizes.

The games were often retooled or even scrapped, so the sets often came across as fairly rinky-dink during their trial runs. That formed the basis of Revillame’s defense when he was accused of aiding the cheating on the show.

The incident in question happened on a segment called “Wilyonaryo” with similar rules to Deal Or No Deal. The contestant had to decide whether to keep the amount offered by Revillame or gamble it all by picking whatever was inside a large, white, poorly constructed wheel.

Initially, the caller wanted to gamble, but Revillame convinced her not to. It was revealed that if the contestant had picked the wheel, she would have lost all her money—suggesting Revillame had previous knowledge of what was inside.

Further complicating the matter was Revillame’s claim that a purple wheel housed the jackpot prize. When he opened up the wheel, it also indicated that the caller would have lost everything. After fiddling with the wheel, Revillame suspiciously peeled away another number, this time indicating a jackpot victory.[7]

Producers claimed that it was an honest mechanical glitch rather than a sign of shenanigans. The Department of Trade and Industry disagreed and fined the show the equivalent of around $5,700 (in November 2017 US dollars).

3 The Our Little Genius Scandal

Mark Burnett Cancels His Own Show

In the lead-up to Our Little Genius’s premiere, there had been a significant amount of backlash about the show’s premise. Critics argued that it placed too much pressure on young children, who would be asked trivia questions that could potentially result in the acquisition of “life-changing money” for their families.

As it turns out, the show was canceled before any episodes aired. However, pushing kids toward nervous breakdowns had nothing to do with it. The show’s creator, Mark Burnett, stated at the time that he “discovered that there was an issue with how information was relayed to contestants during the preproduction.”[8]

A contestant’s parent sent a letter to the Federal Communications Commission stating that they had been advised which topics to study and had received direct answers to at least four questions. For instance, the letter claims that they were told, “It was very important to know that the hemidemisemiquaver is the British name for the sixty-fourth note.” If you take just one thing away from this listicle, let it be the hemidemisemiquaver.

Contestants were allowed to keep their winnings, and Burnett initially planned to reshoot the show. However, likely due to the resulting controversy, the show has never reemerged.

2 Million Dollar Money Drop Cheats Couple Out Of A Correct Answer Through Poor Research

In the Million Dollar Money Drop, contestants start off the show in possession of a million dollars. The entire amount must be gambled over a series of questions, and they get to keep whatever remains at the end.

On the first aired episode of the show in 2010, Gabe Okoye and Brittany Mayti lost $800,000 on a question that asked whether the Macintosh computer, Post-it notes, or the Sony Walkman was the first product sold in stores. They answered Post-it notes. According to the emcee, the “correct” answer was the Sony Walkman.

The show had failed to take into account a four-city test marketing campaign for Post-it notes that happened in 1977. They were sold under the name “Press & Peel,” but we’re still counting it.[9] The Walkman was first released in Japanese stores in 1979—two years later.

The show’s executive producer offered the contestants a chance to return to the show to play again. Unfortunately, the show was canceled before they had a chance to take him up on the offer.

1 A Wanted Fugitive Wins Big On Super Password

In 1988, a man calling himself Patrick Quinn appeared on Super Password and won $58,600 over the course of four days. It was a supremely risky move because he was a wanted fugitive with outstanding fraud warrants. Among his crimes was the staging of his wife’s death to collect her $100,000 insurance policy.

It turned out that Patrick Quinn was actually the name of one of the fraudster’s college professors. The contestant’s real name was Kerry Ketchem. A bank manager recognized him and subsequently called the Secret Service.

Shortly after, Ketchem phoned the show’s producers and claimed that he needed to leave the country imminently on a business trip. He made arrangements to pop over to their offices to collect the money in person instead of the standard procedure of receiving the check in the mail.[10]

When Ketchem arrived, local officials arrested him. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t get to keep his winnings. The show’s judges contended that he was in violation of contestant eligibility rules because he had used a false identity. Ketchem was also sentenced to five years in prison for insurance fraud.

You can read more of David’s writing at CultureRoast.com and check out his videos at YouTube.com/CultureRoast

Read more weird facts about TV and radio competitions on 10 Weird Facts About Game Shows and 10 Insanely Misguided Radio Competitions.