History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

Top 10 Insights And Mysteries Gleaned From Ancient Tombs

Sometimes, an old grave is like a code. Crack one, and it might release a torrent of new information or twist a mystery even tighter. In recent years, many pivotal insights into human behavior and strangeness were triggered by grave goods, skeletal injuries, and even tomb architecture.

No grave is so universal as to forget the person within. Whether the tombs contain important officials, laborers, or infants, these final resting places can reveal emotions, daily moments, and the enigmatic games they loved to play.

10 St. Alban’s Abbot

St. Albans Cathedral was named for the first saint of Britain, who was killed at the site by the Romans. Dating from Norman times, it also holds the honor of being the country’s longest active place of Christian worship.

But St. Albans has its mysteries. One of its most successful abbots was John of Wheathampstead. After his death in 1465, nobody could remember where he was buried.

In 2017, archaeologists stuck their spades into the cathedral’s burial ground but focused mainly on the graves from 1750–1850. Then an anonymous skeleton showed up.

The team scratched their heads until they found three papal seals from Italy. The lead artifacts were unique to archaeology and also identified the remains as Abbot John’s. During 1423, he traveled for an audience with Pope Martin V. The Pope granted him the three seals, a kind of public charter and privilege for the abbot’s monastery.[1]

The mystery of another grave at St. Albans remains unsolved. In the same year, a child was exhumed, holding what appeared to be a rosary. This indicated a Catholic burial in a Protestant graveyard, something highly unusual for the time.

9 Unknown Native American Group

In 2010, archaeologists became the first people in 11,500 years to view a buried child. The six-week-old girl was found with two other babies in the Tanana River Valley in Alaska. In 2018, researchers announced that her DNA revealed the existence of a previously unknown group of migrants.

All living Native Americans descend from two ancestor pools, the northern and southern branches. The Tanana River girl belonged to neither, yet she shared genetic material with Native Americans alive today.

Her genome is quite special. It is the second-oldest genome to come out of North America, and scientists have never seen anything similar. The unknown ancestral group was older than the other branches.[2]

Now called the Ancient Beringians, after a route long suspected to have brought people to the western hemisphere, their discovery strengthened two ideas—that the ancestors of all Native American tribes came from Siberia and that nobody hurried across Beringia and scattered in every direction. Instead, they lingered there and became isolated from other Asian groups for thousands of years until they formed distinct genetic groups.

The Ancient Beringians did so 20,000 years ago, and the northern and southern branches split off about 4,000 years later.

8 Egyptian Working Conditions

Gebel el Silsila is an archaeological site in southern Egypt that is mostly known for the graves of worker-bee Egyptians. From 2015–2017, fieldwork extracted several kinds of tombs. Some were shallow, mere hollows topped with rocks. Others appeared to hold entire families. One sector of the cemetery was used to bury children and adults who died 3,400 years ago.

The skeletons revealed the kind of physical labor that would attract the wrong sort of attention from unions today. In addition to backbreaking tasks, the deceased apparently worked in high-risk conditions. A lot of their injuries included long bone fractures.[3]

On the positive side, most breaks were in an advanced state of healing. Gebel el Silsila’s workforce may have been exposed to more accidents than normal, but they received crack medical services.

They were not up starvation creek, either. There was almost no sign of malnutrition, and researchers collected a rough menu from animal remains found at the site. These included Nile fish, mutton, goat meat, and crocodile.

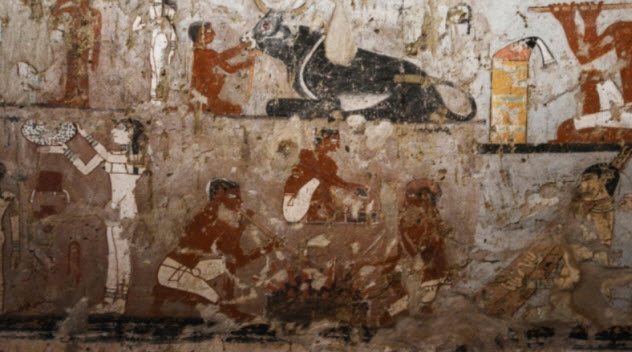

7 Personal Moments Of A Priestess

In 2018, another tomb was unearthed in Egypt. Found near the Great Pyramid of Giza, it once held an important woman. During her life, Hetpet was a priestess of Hathor, the goddess of fertility and childbirth. Hetpet died around 4,400 years ago and was interred in a cemetery for officials.

Upon entering, archaeologists found the tomb contained an L-shaped shrine and wall art. The paintings were pristine and showed several scenes from Hetpet’s life. The position as priestess already revealed that she was a powerful official with ties to the royal palace. But the murals depicted her as a mother receiving offerings from her children as well as Hetpet being present during several hunting and fishing activities.

There were festive scenes with music, dancing, and monkeys that appeared to be pets. One of the animals was shown dancing in the presence of an orchestra. This incredibly rare scene has only been found once before in a tomb from ancient Egypt. Experts are confident that, in time, Hetpet’s tomb will reveal more information and artifacts than just her private life.[4]

6 Prehistoric Frail Care

Around 100,000 years ago, a healthy child received a blow to the head. The skull fractured inward and caused permanent brain damage. The youngster’s short life showed interesting social dynamics when his or her grave was found in 2014. It was located between other prehistoric graves at Galilee’s Qafzeh cave site.

Researchers were curious about the injury. The blow was delivered to the front of the head and left the child incapable of self-care. But the youngster, whose gender could not be determined, did not die immediately. As horrific as the blunt force trauma was, he or she lived for several more years.

It taught researchers that this handicapped child was loved. Despite the severe challenges, other people provided care for an additional five or six years until the child died at age 12 or 13. Deer antlers decorated the teen’s chest. Since none were found in the other graves, it could have marked the child as a special member of their community. Indeed, his or her long-term care is among the earliest displays of human compassion ever found.[5]

5 Islamic Writing In Viking Graves

At the Swedish sites of Birka and Gamla Uppsala, burial garments were taken from Viking graves. Experts dismissed them as typical. This assessment saw them languish in storage for over a century.

But in 2017, a fresh study of over 100 pieces discovered woven writing on 10 fragments. Unexpectedly, the characters were Arabic Kufic script. Two words kept repeating together—“Allah” and “Ali.”

The reference to God and Ali (Muhammad’s cousin) only appeared the right way when viewed in a mirror. This was not unusual. But unlike other known examples of the two names done in mirror writing, they were neither accompanied by the normal version of the words nor by the prophet’s name.

The unique depiction makes for divided opinion. Some believe that the Vikings, who had contact with the Islamic world, simply copied the tradition but in a wrong or shoddy way. Others believe that it could be a groundbreaking new clue to Islam’s influence in Viking-era Scandinavia. This second view also considers that the individuals in the graves could have been Muslim. The debate needs more evidence to settle things either way.[6]

4 Jebel Qurma’s Puzzling Graves

In Jordan’s desert, hundreds of tombs belong to a mystery. In 2017, the desolate Jebel Qurma yielded cemeteries of ancient communities that strangely came and left for thousands of years.

To better understand this pattern, researchers dated the burials. A grave-lacking period pointed at another exodus. In this manner, the tombs suggested that the region was mostly abandoned between the third to the first millennium BC. After about 1,000 years, the graveyards were used again, this time by a society that did not make ceramics. Another necropolis founded 8,000 years ago received new burials from AD 100 to 400.

Why Jebel Qurma saw wholesale abandonment and then arrivals is unclear. Climate change could have driven this cycle, although evidence is lacking. Another plausible explanation is that nobody left and archaeologists have yet to find their traces from certain eras.[7]

Another mystery is why the tombs became enormous in the late first millennium BC. Constructed with flat slabs and resembling towers, some weighed up to 300 kilograms (660 lb).

3 Oldest Toy Collection

Siberia is home to the oldest toy collection in the world. Sadly, most pieces came from the graves of children. In 2015, the earliest baby rattles were found buried near Lake Itkul. Arranged on an infant’s chest, eight figurines were carved with detailed human and animal faces.

Another toy or rattle was added to the collection when a fisherman snagged it in a river. It depicted a pagan god with a terrifying expression. However, the most intriguing additions arrived in 2017 during excavations at Itkol II in southern Siberia.

Around 4,500 years ago, the Okunev culture said goodbye to a child. They belonged to the same people who carved the river idol. In this case, they added a doll and a toy animal. Neither had bodies anymore. Made from organic material, they had dissolved a long time ago.[8]

The doll’s head and intricate face were fashioned from a piece of soapstone. The animal was shaped from horn. It is not clear what species it represents, which could make the creature mythical instead of real.

The toys revealed a prehistoric affection for children. Effort went into making playthings for the kids to enjoy. It also showed mourning and an attempt to comfort the children by adding toys to their graves.

2 Ancient Roman Board Game

In 2006, a wooden board was found among the grave goods of a Germanic aristocrat. It was added to the tomb in Slovakia around AD 375. Showing a touch of chess, the surface was divided into squares, but that was where all things familiar ended.

Though mysterious, the board is not the first trace of this game. Similar playing fields adorn the floors of Roman and Greek temples from 1,600 years ago. The Slovakia board, however, is the best portable example and also came with what could be the playing pieces. Made of glass, they came in green and white. The deceased probably learned the game while serving in the Roman army.

But to learn it today is a feat that still escapes experts. Trying to figure out how to play an extinct, ancient game is extremely difficult. Researchers are not entirely clueless. They suspect that the game was a variant of Latrunculi, sometimes called Ludus latrunculorum. In turn, Latrunculi was based on petteia, an ancient Greek game.[9]

The discovery has already made a contribution to the ancient games of Europe, but understanding its rules will greatly add to this history niche. Unfortunately, no complete set rules from Latrunculi or petteia has been preserved.

1 A Human Spiral

Mexico is no stranger to weird ancient burials. But when a mass grave was recently opened at Tlalpan, a strange arrangement made archaeologists look twice. Ten individuals formed a chain-like spiral, woven together by their interlocking arms.

The gender of only three could be determined (one male, two females), but the skeletons consisted of adults, a baby, and one older child. The burial showed strong ritualistic suggestions, but it remains unclear if they were sacrificed or given a communal burial after dying from different causes.[10]

The small group predates the Aztecs and belonged to a 2,400-year-old village. Found in 2006, the settlement survived for about 500 years. This placed it between two important eras of Mexico’s early history: the Ticoman phase (400–200 BC) and the Zacatenco phase (700–400 BC), which was one of the first major recorded civilizations.

Archaeologists are hopeful that the unusual skeletons, some showing artificially deformed teeth and skulls, will add more understanding to the earliest people of Mexico. Any new data could help solve the riddle of why their societies disintegrated so quickly.

Read more about bizarre tomb discoveries on Top 10 Unexpected Discoveries Involving Tombs and 10 Most Bizarre Tombs Ever Discovered.