Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Outlaws Of The Public Enemy Era Almost Forgotten By History

The term “public enemy” first began being used in the United States during the 1920s. The FBI later adopted the term in its early days to describe wanted criminals. Add to this the fact that Prohibition and the Great Depression sent crime rates soaring, and several historians refer to that period of US history as the “public enemy era.”

It was the time of mobsters and bank robbers. Like the Wild West, people had a tendency to romanticize criminals of that period. Many outlaws like Bonnie and Clyde or John Dillinger became pop culture icons. But the era was filled with many other villainous figures who have almost been consigned to oblivion today.

10 The Barkers

The First Family Of Crime

The Barker gang enjoyed its fair bit of notoriety thanks mostly to its alleged leader and criminal mastermind, Kate “Ma” Barker. She has often been depicted as a heartless, calculating killer. However, historians have trouble establishing what criminal activity Ma Barker was involved in (if any).

While she certainly had knowledge of her sons’ illicit dealings, there is no evidence to suggest that Ma Barker took part in or planned any of it. In fact, Barker gang associate Harvey Bailey once said she “couldn’t plan breakfast.”[1]

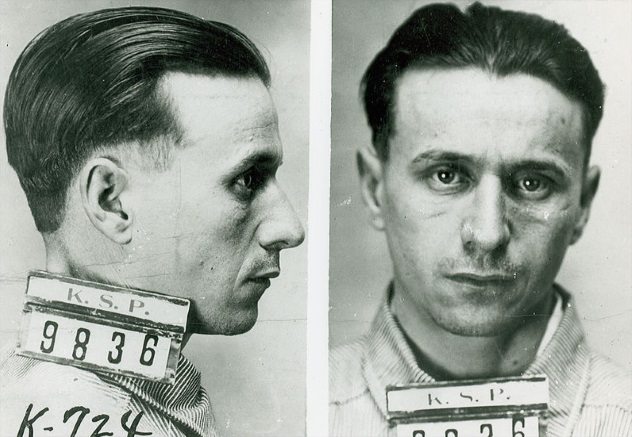

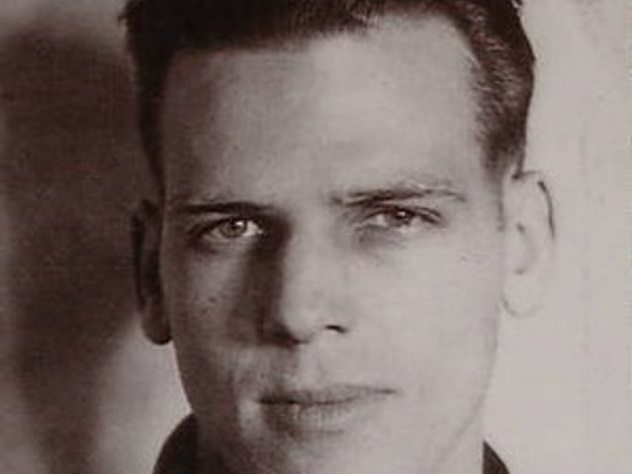

The likely leader of the gang was Fred Barker (pictured above), Ma’s youngest son. Although the Barkers had been in trouble with the law for decades, it wasn’t until 1931, when Fred met Alvin Karpis in prison, that the gang officially formed. By this time, the oldest son, Herman Barker, had committed suicide while on the run for killing a sheriff’s deputy, and the second-youngest, Arthur Barker, was already in jail for gunning down a night watchman. Arthur was released from prison in 1932 and joined the gang, which was already responsible for multiple robberies and murders.

Unsurprisingly, all the Barkers met violent ends. Fred died in a shoot-out with FBI agents in 1935, in which Ma Barker was also killed. Arthur died trying to escape from Alcatraz. The remaining son, Lloyd Barker, was killed by his wife in 1949.

9 Egan’s Rats

The Untouchables

At the peak of its power, the St. Louis–based gang known as Egan’s Rats boasted approximately 400 members. Its leaders openly discussed their criminal activities (including murder) in newspaper interviews without consequence. They were virtually untouchable because one of its founding members was a Missouri state senator.[2]

The gang emerged from the Irish slums of St. Louis during the late 19th century. It was led by two childhood pals—Thomas “Snake” Kinney and Thomas Egan. As the gang grew, Kinney went into local politics, running for the Democratic City Committee. Meanwhile, Egan and his thugs strong-armed people into voting for him. Kinney got elected, and the power of Egan’s Rats grew. They used the same tactic, but on a larger scale, in 1904, when Kinney successfully ran for state senator.

During the first quarter of the 20th century, the gang had a hand in almost all criminal activities in St. Louis. They dabbled in smuggling, bootlegging, extortion, and murder, although bank robberies and armored car hijackings remained their preferred pastime.

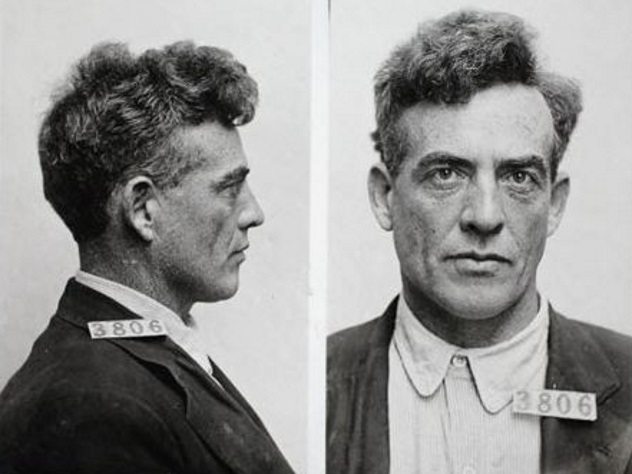

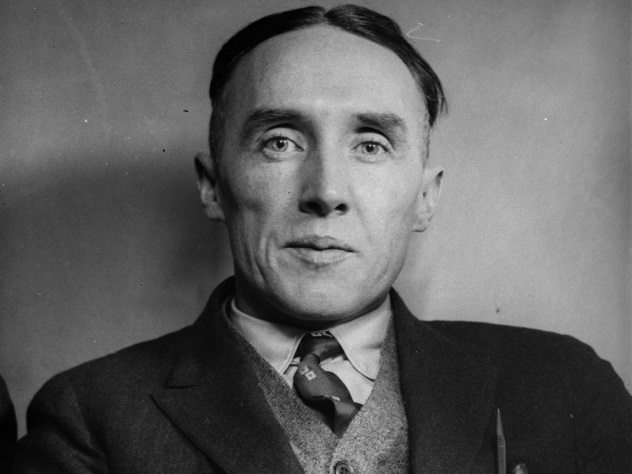

By the 1920s, the gang’s influence had diminished. Both founders were dead, and Egan’s Rats, now led by William “Dint” Colbeck (pictured right above), were involved in a bloody war with a rival gang led by “Jelly Roll” Hogan. The final blows came in 1924—one imprisoned member started talking to prosecutors, and a failed mail robbery led to many important members receiving long prison sentences.

8 Roy Gardner

The King Of The Escape Artists

In an era of outlaw gangs and mob outfits, Roy Gardner was a lone wolf. He pulled off his first score in 1920, when he robbed a mail truck in San Diego. He got caught three days later and sentenced to 25 years at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary.

This is where Gardner began his reputation as “King of the Escape Artists.” On the train ride to prison, Gardner yelled, “Look at that deer!” which caused enough of a distraction for him to disarm the guards and escape.[3]

Soon afterward, the lone wolf robbed a train but was caught days later. Again, he was sentenced to 25 years at McNeil. During the train ride, Gardner retrieved a pistol hidden in a bathroom by an associate and managed to escape. This time, he was recognized at a hotel, captured again, and given 25 years at McNeil.

The third time, Gardner actually arrived at the penitentiary, but he escaped six weeks later during a prison baseball game. He convinced two other inmates to run with him, telling them he’d paid off the guards to miss on purpose. In reality, he just wanted decoys to give the guards more targets.

Gardner was captured again, sent to Leavenworth, and later transferred to Atlanta Federal Prison. He made two escape attempts by digging a tunnel on one occasion and taking three hostages on another, but both failed. In 1934, Gardner was transferred to Alcatraz, where he stayed until 1938, when he was released through a clemency appeal.

7 Harry Pierpont

The Man Who Taught John Dillinger

Bank robber and murderer Harry Pierpont is best remembered today for being a friend and mentor to the immeasurably more famous John Dillinger. In fact, some have speculated that Pierpont was the actual leader of the Terror Gang but preferred to have Dillinger as the face of the outfit due to his natural charisma.

Pierpont first met Dillinger in 1925, while both were serving time at Indiana Reformatory. Although Pierpont was just a few months older, he was a much more experienced robber, having already pulled several scores with his old gang.

When Dillinger got out of jail, Pierpont still had years left on his sentence, but he had an escape plan ready. All he needed was money, so Dillinger resumed his criminal career to fund the jailbreak. On September 27, 1933, Pierpont and several accomplices broke out of prison.[4] However, Dillinger was arrested for his part and imprisoned in Lima, Ohio. Not wanting to leave his protege behind, Pierpont organized another jailbreak for his friend. Although successful, Pierpont had to kill the sheriff.

Based out of Chicago, the newly formed gang went on a spree of audacious heists, including an assault on a police station to raid its arsenal. The gang’s success ended with Dillinger’s death in a bloody shoot-out. The remaining members were captured one by one, and Pierpont died in the electric chair in 1934.

6 Ford Bradshaw

Oklahoma’s Number-Two Criminal

Depression-era bank robber Ford Bradshaw was doomed by history to remain in the shadow of fellow Oklahoma Sooner and rival criminal Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd. Technically, Bradshaw was more successful as a bank robber than Floyd. However, while the former stuck to low-profile targets in small towns throughout Oklahoma, the latter went after big scores in cities like St. Louis, Akron, and Kansas City. Floyd even earned infamy for his role in the Kansas City Massacre, and some historians aren’t convinced he even took part in that shoot-out.

Meanwhile, Bradshaw was content prowling Oklahoma throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, often partnered up with other Cookson Hills outlaws, particularly the “Tri-State Terror,” Wilbur Underhill Jr.

Bradshaw’s downfall started on December 26, 1933, when Underhill got in a shoot-out with officers in Shawnee, Oklahoma. Underhill was gravely wounded and later died in a prison hospital. Angered by his friend’s demise, Bradshaw and his gang decided to shoot up the town of Vian in retribution.[5] This finally garnered Bradshaw the federal attention that had mostly eluded him up until that point in his criminal career. He died a couple of months later in a shoot-out with sheriffs in Ardmore, Oklahoma.

5 James Lucas

The Man Who Tried To Kill Al Capone

James Crittenton Lucas was a criminal who got sentenced to 30 years in prison for robbing the First National Bank in Albany, Texas. However, it wasn’t until he arrived at Alcatraz in 1935 that Lucas started gaining national notoriety.

Even though Lucas was only 22 years old, he became one of the prison’s most problematic inmates. He often caused trouble, got involved in a work strike, and, most notably, attempted to kill fellow inmate Al Capone in 1936. Lucas attacked the renowned mobster in the shower with a scissor half, dealing Capone superficial cuts to his hands and chest. Lucas later claimed this was due to Capone threatening to kill him.

Lucas made the headlines again in 1938, when he tried to escape from Alcatraz with two other inmates, Rufus Franklin and Thomas Limerick.[6] The three men assaulted supervising guard Royal Cline and planned to overpower the tower guard as well. However, they failed to get the drop on Cline, and he shot both Limerick and Franklin. Officer Cline and Thomas Limerick died, while Lucas and Franklin received life sentences for murder.

Despite his new sentence, Lucas was still paroled in 1958 and became one of the few gangsters from the public enemy era to enjoy a long, happy life. He married, had four kids, found a law-abiding job, and lived until 1998.

4 Verne Sankey

America’s Leading Kidnapper

Bootlegging and bank robbery were the preferred pastimes of criminals during the 1920s and 1930s, but Verne Sankey showed there was another highly lucrative alternative—kidnapping. Sankey, along with accomplice Gordon Alcorn, pulled off a couple of high-profile abductions that resulted in big paydays. Their modus operandi was later copied by other criminals like the Barker gang and “Machine Gun” Kelly.

Initially, Sankey and Alcorn took to bank robbery. In June 1932, they found themselves in St. Paul, Minnesota, and decided to try their hand at kidnapping. Their target was Haskell Bohn, the son of a local entrepreneur. The abductors received $12,000 in exchange for his safe return.

Realizing that kidnapping was safer and smoother than bank robbery, Sankey and Alcorn started looking for a bigger target. Seven months later, they kidnapped millionaire Charles Boettcher II from his home in Denver, Colorado, and held him for a $60,000 ransom.[7]

Sankey left Boettcher’s wife, Anna Lou, a note. It demanded, among other things, that she didn’t alert the cops, reminding her what happened to the Lindbergh baby after his father called the police. Because of this note, Sankey and Alcorn became prime suspects in the Lindbergh kidnapping before the arrest of Bruno Hauptmann in 1934.

3 Gerald Chapman

The First ‘Public Enemy No. 1’

Although Gerald Chapman is mostly forgotten today, he was considered the first “celebrity criminal” of his time. The media gave Chapman the spotlight by awarding him monikers such as “the Gentleman Bandit,” the “Super-Bandit,” and, most notably, the first “Public Enemy No. 1.”[8]

Chapman’s first arrest led to him being sent to Auburn State Prison for bank robbery. That is where he met George “Dutch” Anderson, who became his mentor and partner in crime. Anderson was a highly educated Danish thief and con man; he was born into a wealthy family but chose a life of crime. Even so, Dutch still emanated an air of sophistication which Chapman enjoyed and tried to emulate.

The two men were released in 1919 and, with the “Noble Experiment” of Prohibition around the corner, promptly set up a bootlegging business. In 1921, Chapman and Anderson teamed up with another man, Charles Loeber, and committed a string of robberies. This included robbing a mail truck where they made off with a massive haul in cash, stocks, bonds, and securities. However, they only managed to elude police for a few months. Loeber turned on his partners, and both Anderson and Chapman got 25 years at Atlanta Federal Prison.

Chapman and Anderson escaped prison separately and resumed their criminal partnership. However, during a burglary, Chapman killed a patrolman. He was, again, identified by an accomplice, and this time, he was sentenced to hang.

2 Frank Nash

Most Successful Bank Robber In US History

Frank “Jelly” Nash has frequently been touted as the most prolific American bank robber of all time, having allegedly participated in 200 bank heists and over a dozen train robberies.[9] However, he is still best remembered for his failed escape attempt, which became known as the Kansas City Massacre.

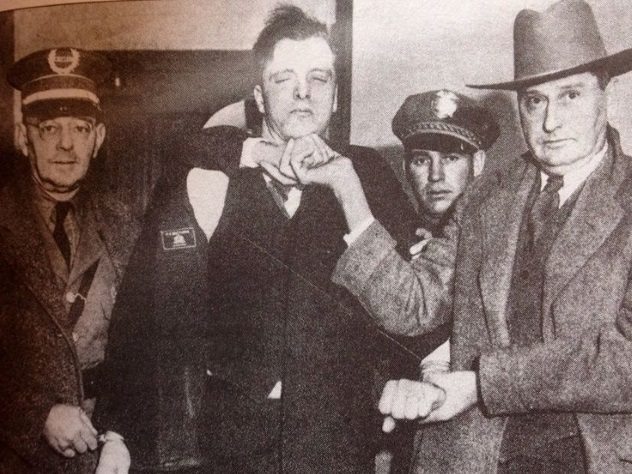

Nash was first convicted in 1913. He spent the next two decades either committing robbery, planning to commit robbery, or doing time for robbery. In 1933, Nash was on the run after escaping from prison three years prior. Two FBI agents, Frank Smith and Joseph Lackey, tracked him to Hot Springs, Arkansas. They made the arrest along with police chief Otto Reed.

The morning of June 17, 1933, Nash was transported to Kansas City, Missouri, and was promptly surrounded by multiple detectives and FBI agents. While being loaded into a car, three men approached the officers and opened fire with machine guns. Chief Reed, one FBI agent, and two local detectives were killed, as was Frank Nash. One shooter was identified as gun-for-hire Vernon Miller. The other two were never formally identified, although Pretty Boy Floyd and his partner Adam Richetti were implicated.

If the goal was to rescue Nash, then the job obviously failed miserably. However, some historians contend the plan all along was to silence the bank robber, not free him. Vernon Miller was executed a few months later, perhaps by someone continuing to tie up loose ends.

1 Leo Hall

The Kitsap County Killer

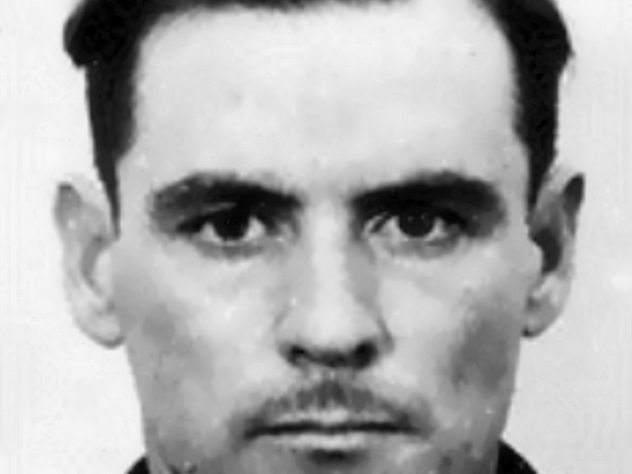

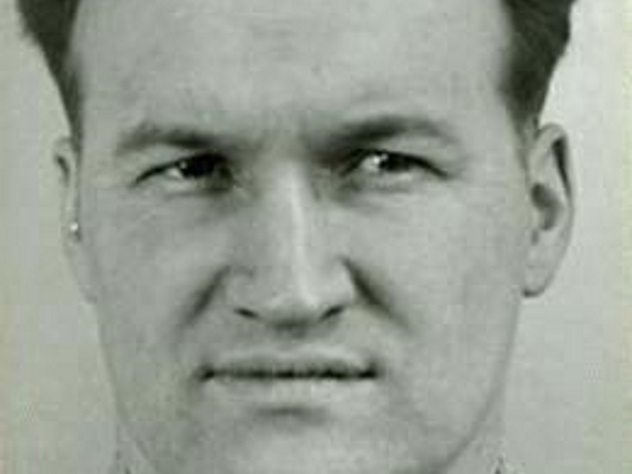

Despite being one of the most violent, gruesome crimes of the 1930s, the Erland’s Point Massacre is almost forgotten today, as is its perpetrator. Leo Hall wasn’t a criminal mastermind who robbed banks up and down the country. He was a dockyard worker and former boxer who botched one score and killed six people.

Back in 1934, Hall and his accomplice, a barmaid named Peggy Paulos, targeted a beachfront home in Erland’s Point, Bremerton, Washington. The swanky house belonged to retired couple Frank and Anna Flieder, but it was supposed to be empty the night of the robbery. Instead, Hall and Paulos broke in on a party in full swing.

Six people were at that party, although only five were present when the robbers came in, as one was off on a beer run. Hall and Paulos bound and gagged them while they ransacked the place. When the sixth partygoer returned, he fought Hall, but the ex-prizefighter beat him to death. Whether or not this was Hall’s plan all along is unknown, but after the scuffle, Hall went around all the other hostages and shot or stabbed them to death. At this point, Peggy Paulos ran away, fearing for her own life.

Hall almost got away with it, as police had no leads, but Paulos eventually went to the authorities 18 months after the massacre. Hall was convicted and hanged in front of a record crowd at Walla Walla State Penitentiary.[10]

Read about more not-so-famous criminals on Top 10 Fascinating Yet Obscure Gangs Of The Wild West and 10 Lesser-Known Yet Brutal Serial Killers.