History

History  History

History  Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

10 Ponzi Schemers Who Conned Their Way To A Fortune

Named after Charles Ponzi, Ponzi schemes come in all shapes and sizes but have certain elements in common. The details of the supposed business are often vague or mysterious. They promise high rates of return for little risk and often come with a deadline to panic investors into putting in money before they properly consider the investments. But unlike true investment, there are no business returns. Dividends paid to investors are generated not from business returns but from the capital put up by new investors.

Eventually, the flow of new investors will inevitably dry up, at which point the whole thing collapses under its own weight, and the originator of the scheme can usually be found on his way to the nearest airport with his luggage stuffed with dollar bills.[1] And Ponzi schemers, much like their investors, come in all shapes and sizes.

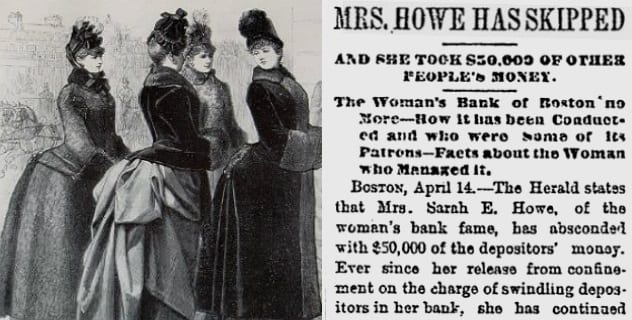

10 Sarah Howe And The Ladies’ Deposit Company

In 1879, Sarah Howe, after a sketchy career as a clairvoyant, decided to become a banker. She opened the Ladies’ Deposit Company, which was either a charity offering safe havens for women, an investment opportunity, or a bank, depending on who she was talking to at the time.[2]

Only single women of modest means were allowed to make deposits, in amounts less than $1,000, for which she offered a tasty eight-percent interest rate per month. It was, she said, a means to give women a helping hand and make them financially independent. The target audience was, coincidentally, the group with the least power and influence and therefore the least likely to complain.

Withdrawing money from the bank was difficult. Depositors were only allowed to withdraw the interest and not the capital. She gave the reason for this as “to prevent them wasting their money on fripperies.” Perhaps Howe wasn’t quite the radical feminist she had appeared to be. When Howe began to flaunt her newfound wealth, some investors felt anxious, and someone contacted the Boston Daily Advertiser, which launched an investigation. They declared the bank a scam.

Howe did attempt to pay some claims, but by the time the scheme folded, investors had lost around $30,000. She was jailed for three years, and on her release, she set up an identical scheme, the “Woman’s Bank of Boston,” which netted her another $50,000. After that, having learned from her past mistakes, she scarpered.

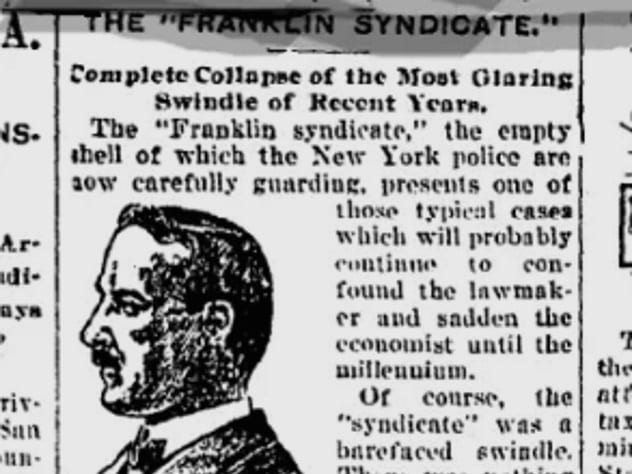

9 William Miller And The Franklin Syndicate

In March 1899, William Miller launched the Franklin Syndicate, promising a ten-percent return on investments each week, or 520 percent annually. Miller, who, for obvious reasons, was nicknamed “520 Percent,” claimed to have inside information on what made businesses profitable, though, of course, he was rather cagey about details. He began by persuading three of his friends to invest. He even guaranteed their investment against loss. The original investors were then encouraged to bring in further investors on the promise of a five-percent commission.

When he had exhausted friends and relations, Miller took the scheme wider, advertising across the US, again promising high interest and no risk and stating, in writing, that his investments were based on inside information. He took advantage of the new art of public relations to place favorable articles with headlines such as “Wall Street Astonished. William F. Miller’s Franklin Syndicate a Big Winner. 10 Per Cent. a Week Profit. All Former Efforts in Financial Operations Eclipsed by a New Wizard in the Realms of Stock Manipulation.” At one point, his home was surrounded by people desperate to invest, while every available space inside was stuffed with cash.

Miller’s downfall came after he took on a partner, Edward Schlessinger. Schlessinger was perhaps shrewder than Miller, and he demanded his cut be paid in cash each day. This meant that they had to keep records. Schlessinger took his money and hid it, but Miller didn’t bother, thinking that the scheme would go on indefinitely. Miller defrauded his investors of $1 million—equivalent to over $25 million today.

The scheme attracted the scathing attention of the press, and by November 1899, the net was closing. Schlessinger took his cash and left, never to be seen again. Miller’s attorney, a rather shady lawyer, convinced him to hide his money in the lawyer’s bank account. Miller gave the lawyer everything he owned. The following day, he found out what the lawyer must already have known: that there was a warrant out for his arrest.

Miller received a ten-year jail term, while the lawyer made another deal. He persuaded Miller not to name names, and in return, the lawyer paid the magnificent sum of $5 per week for the upkeep of Miller’s wife and child.

William Miller had been screwed.[3]

8 Ivar Kreuger And The Swedish Match Empire

Ivar Kreuger was a Swedish businessman who founded a match-making company (as in the fire-starting device, not a dating service). During World War I, Kreuer controlled Sweden’s entire match industry, and after the war, he aimed to extend that monopoly to the rest of the world. Kreuger began to expand his business worldwide and started moving his money between his companies in order to artificially inflate their profits. By the end of the 1920s, Kreuger owned around 200 companies, including several banks. And then came the Wall Street Crash.

Kreuger used his own banks to finance his companies. He invented the “dual-class” ownership of shares, meaning that he retained control of his companies while still selling his shares and doubling the size of his capital. He also “pioneered” the use of off-balance sheet entities, meaning that a company’s finances might not appear in the parent company’s financial statements, thus becoming invisible.

Kreuger was an inveterate gambler, using both his own money and that of the businesses he controlled. He made speculations in foreign currencies, and by 1932, things were becoming desperate. He gambled with the securities of his companies to try to reverse their falling stock market value. At one point, he needed to raise the equivalent of $150 million to cover his losses. Kreuger signed loans with foreign governments, without any idea of how he was going to repay them. By the time his empire fell, he had lost up to $1.5 billion in today’s terms. He negotiated a number of huge government loans, using the loans to make the first repayments, a classic Ponzi-style move.

By 1932, Kreuger’s creditors were uneasy. On the morning of a scheduled meeting with the French national bank, he shot himself dead. Several notes were found next to him. Subsequent investigations revealed that many of his supposed assets were nonexistent.[4]

7 Jean-Pierre Van Rossem And Moneytron

Jean-Pierre Van Rossem was a millionaire Marxist anarchist who once owned a Formula One racing team. He was a novelist, a politician, and a drug addict. And a convicted fraudster. Born in Belgium in 1945, Van Rossem was, shall we say, colorful. He published a guide to Belgium’s brothels, using little condoms instead of stars when rating them for hygiene, comfort, and, er, value for money.

Van Rossem was not the sort of man who would be put off by little things like regulations. He named his company Moneytron, the name of his alleged “supercomputer,” with which he could predict the stock market. Of course, no one ever saw the machine. For a while, the machine appeared to work, and his client list resembled a Who’s Who of international investors. Van Rossem’s fortune rose to hundreds of millions of dollars, with which he treated himself to a yacht, two planes, 108 Ferraris, and the aforementioned Formula One team.

By 1990, however, things didn’t look quite so hot. Van Rossem blamed his clients: “My clients blindly believed me.” Clearly, it was their own fault.

Van Rossem was jailed for five years, and while he was inside, he spent his time wisely. He entered politics, running for a seat in parliament. He formed his own party, which he named the Radical Reformers and Social Warriors for a Fairer Society. One of his campaign slogans was, “No nagging, everybody rich.”[5] Karl Marx would have been proud.

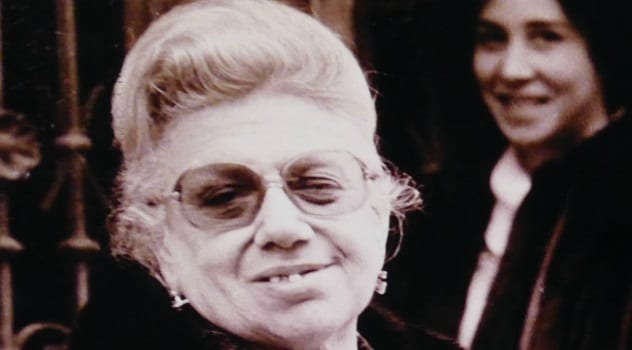

6 Dona Branca And The Ten-Percent Interest Bank

In 1970, Maria Branca dos Santos, or Dona Branca, as she is usually called, opened her own bank in Portugal. Despite her lack of experience in the world of finance, Branca was able to offer interest rates of ten percent per month. She ran her bank for 14 years and was often referred to as the People’s Banker because of her willingness to take money from the relatively poor. [6] Someone give that woman a medal.

At one point, police were called in to control the crowds outside her house who were waiting to deposit their life savings at the “bank.” The bank was a one-woman operation, so much so that at one point, she suspended payments so that she could take a vacation. That seems reasonable; she must have been exhausted counting all that money.

Like all Ponzi schemes, however, the good times could not last for ever. In 1984, knowing that the game was up, she tried to flee. The police arrested her at the airport as she waited to board a flight to Rio de Janeiro. She was sentenced to ten years in prison. The money was gone.

5 Adriaan Nieuwoudt And The Kubus Scheme

During the 1980s, Adriaan Nieuwoudt, a fresh-faced South African guy, set up a business cultivating milk cultures. He claimed to have developed the business from his grandmother’s homemade skin care cream.

Basically, a small amount of “activator product” was sent to the investor. When soaked in milk, the activator product produced “kubus” (really just more of the same stuff), which was then dried and sent back to Nieuwoudt, ostensibly to be used in beauty products. However, the products didn’t exist.

Nieuwoudt merely took the stuff that was sent back, relabeled it, and sold it to new investors as “activator product.” The beauty of the scheme was that investors were themselves manufacturing the bait with which to hook more investors.[7] Thousands of people invested in the scheme, which was eventually declared illegal by the South African government.

Undeterred, however, Adriaan Nieuwoudt went on to try more business ideas. There was the scheme to harvest the kaolin deposits he claimed to have found on his land. There was the tourism “master plan” to corral tourists in a central area on the Orange River, to avoid muggers. There was the carbon credit scheme, which would provide green energy to remote areas. All of these required investors to deposit large sums of money with very little guarantee, except, of course, his word.

Nieuwoudt wasn’t jailed for the kubus scheme, though he was later sentenced to ten years in jail for diamond smuggling.

4 Ron Rewald And His Nonexistent Partners

Ron Rewald spent the late 1970s and early 1980s living in luxury in Hawaii. He appeared to be a successful businessman with very prominent friends. He also claimed to have several degrees (including one from MIT), to have been a professional football player, and to have worked for the CIA.

Rewald ran an investment company, which he called Bishop, Baldwin, Rewald, Dillingham & Wong, where he was purportedly a partner, but in truth, he ran the whole show. He began to offer investments with 20-percent returns that, he said, were underwritten by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and therefore a “sure thing.” He claimed that his company had 157 employees all over the globe, but the too-good-to-be-true opportunities, along with Rewald’s lavish spending, raised suspicions. A TV company began to investigate.

In 1983, Rewald was found in a hotel room, having supposedly attempted to commit suicide. A note to his wife was found, in which he implied that his business had been a front for the CIA and that he was only following orders. He later claimed in court that the CIA was supposed to repay investors for their losses and that the money he had spent on mansions, cars, and high living was essential to maintain “cover.” His spy name was “Winterdog.” Of course it was.

Rewald was convicted of 94 counts of fraud, tax evasion, and perjury. He conned approximately $55 million dollars (in today’s terms) from 400 investors. The CIA was forced to admit that they had occasionally used him for telex services, but it seemed unlikely that they would ever have okayed such an expensive operation as Rewald had claimed, especially as it bore zero fruit.[8]

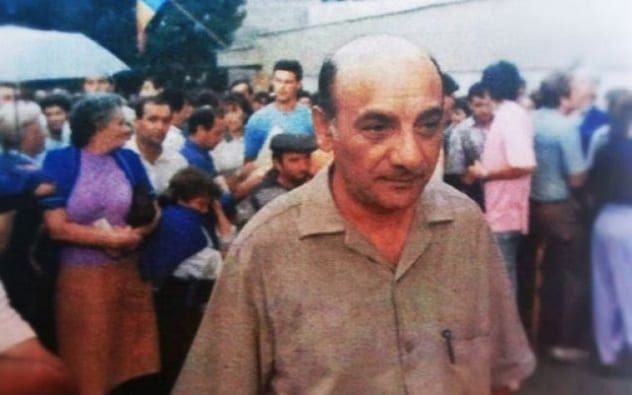

3 Ioan Stoica And The Caritas Scheme

During the early 1990s, Ioan Stoica ran a Ponzi scheme in Romania which promised, and paid, 800-percent profits to its investors.[9] At least, it paid out for the first few months. It is not known exactly how many investors were conned, but it is believed that tens of thousands of poor Romanians invested their life savings in the scheme.

Caritas was so popular because it offered an escape from government-imposed austerity measures and inflation. Investors in the scheme were required to wait approximately three months before withdrawing their capital, but with fantastic profits in return. The 13-week embargo meant that Stoica could use the payments from new investors to pay interest to the old ones, thus giving the appearance of reliability. Early investors spent their interest on luxuries such as washing machines and refrigerators, but few withdrew the capital.

People slept outside Caritas offices waiting to make deposits, some of which were as low as $2. The average wage at that time was $60 a month. Extra trains and buses were laid on to transport the eager investors. During the scheme, Stoica is estimated to have made between $1 billion and $5 billion, a massive amount of money from people who had nothing.

When the fraud was exposed, the government feared rioting in the streets. Though they were suspicious, it is alleged that the president ignored it because he knew that if Caritas collapsed, it could bring catastrophe for his government. The company went bankrupt in 1994, with debts of $450 million. In 1995, Stoica was sentenced to seven years in prison for fraud, which was reduced to two years on appeal and reduced again to 18 months. To date, none of the creditors have gotten their money back.

2 Steven Hoffenberg And The Towers Financial Corporation

Steven Hoffenberg ran one of the biggest-ever Ponzi schemes, selling $475 million in fraudulent bonds.[10]

On paper, Towers Financial Corporatio was a major health care financing company. This entire financial empire, however, had one accountant, which was strange. In 1988, they were charged with selling unregistered securities and reached an out-of-court settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which should have raised concerns. But when a deal looks that good, people often overlook even big red flags.

In 1993, Hoffenberg agreed to plead guilty to fraud charges, in exchange for the government’s recommendation for a lenient sentence. However, the government later withdrew their offer, claiming Hoffenberg had lied to them. Shocker.

Eventually, in 1995, Hoffenberg pleaded guilty to criminal conspiracy and fraud and was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment. Though he was ordered to repay $463 million, most of the money had already disappeared on jets, yachts, and Hoffenberg’s celebrity lifestyle. He eventually settled the suit for $60 million. He was released in 2013 and made the news again in 2016, when he offered to organize a $50 million advertising campaign for election of Donald Trump.

1 Gerald Payne And The Greater Ministries Scheme

Though all con men prey on the gullibility and desperation of their victims, Gerald Payne belonged to a special breed. He was the founder of Greater Ministries International, which cheated 18,000 people out of $500 million during the 1990s. His “ministry” promised church members that they could double their money in under two years.

Their program was, he said, based upon the Gospel of St. Luke. He did add the caveat that the precise profit they made was “up to God” (meaning that if an investor failed to make money, it was because God was choosing to punish him). Nevertheless, he reckoned that God-fearing investors would make money and continue to do so until the Second Coming.

“Donations” were to be invested in gold and diamond mines in Liberia, where Hoffenberg was a “personal friend” of the Liberian president. He also outlined a plan to turn an island in the Bahamas into a theocracy that, though peaceful, would still be armed to the teeth. He had, he said, cleared the plan with he UN, but in case of dispute, they needed to be able to “win at any cost.”

Of course, there was no island in the Bahamas and precious little investment in precious metal or stones. The scheme was a classic Ponzi swindle, using new investments to pay dividends to make the business seem successful. The scheme began to unravel when the Securities and Exchange Commission accused him of selling unregulated securities. Their bank was closed down, and Payne and his associates were charged with fraud and money laundering.

Prosecutors maintained that Payne was a flight risk due to his multiple passports, overseas bank accounts, and stashes of cash around the world. Despite this, Payne was granted bail and, with admirable nerve, continued to raise money. His videotaped appeal for funds said, “It’s not our money; it’s God’s.”

A number of Payne’s co-conspirators took deals to aid the prosecution case against him and admitted that the whole ministry program was a fraud.[11] Gerald Payne was convicted and sentenced to 27 years’ imprisonment. He remains incarcerated today.

Read about more remorseless swindlers on 10 Con Men And Their Masterful Forgeries and Top 10 Famous Con Men.