Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

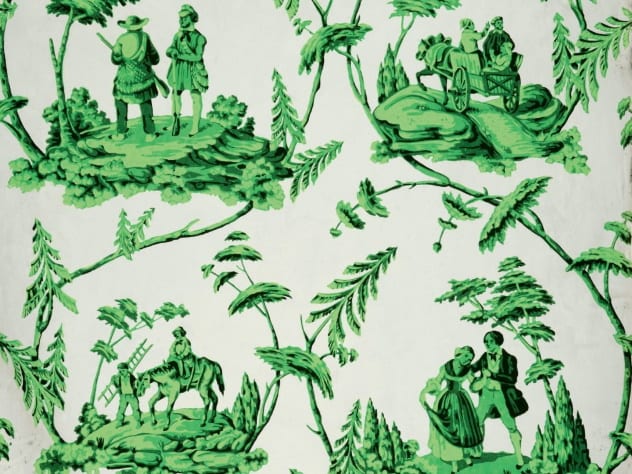

10 Pigments With Colorful Histories

Looking at old photographs, it is easy to imagine that the past was a drab place. Even old paintings can make us think that no one in history enjoyed colorful things. But photos and brown-varnished paintings do not tell the whole story.

To make those paintings in the first place, people had to search out pigments to make paints. To dye cloth, people experimented for years to get just the right color. Some of those experiments went in very odd directions. Here are ten pigments with strange histories.

10 Tyrian Purple

Tyrian purple was once the most highly sought-after pigment in the world. Known as imperial purple, only those of a high status were allowed to wear it. Being porphyrogennetos—born to the purple—meant a person was born into a royal family.

Tyrian purple was one of the most vivid colors available to dyers of antiquity and was desired because unlike many natural dyes, it was resistant to fading. It was also fantastically hard to produce and rare, which only increased its value. According to Phoenician mythology, the dye was first discovered when a dog ate a small mollusc on the beach. When the dog went to lick its mistress, she noticed that its tongue was an intriguing shade of purple. And so Tyrian purple was born.[1]

There is some truth in this tale. Tyrian purple was made from crushing up tiny shellfish, millions of them. The mashed-up molluscs were then left to bake in the sun in a process that caused an unholy stench. 10,000 molluscs would produce a single gram of dye.

Despite being fashionable, the dye could prove deadly. When King Ptolemy visited the Roman emperor Caligula, he wore a vast amount of purple cloth to show off. Caligula, not the most stable monarch, took this as a challenge to his own power and put the king to death.

9 Uranium

Uranium is most famous today as a source of energy in nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. First isolated and named as an element at the end of the 18th century, uranium had actually been used in pigments since at least the first century.[2] A piece of glass from a Roman villa was found to be yellow because it was one-percent uranium oxide.

After the discovery of uranium, it was used extensively to make glass, enamel, and ceramics of a range of colors. The most famous use of uranium was in uranium glass, which has a distinct, and slightly unsettling, green tint under UV light. The fashion for uranium pigments went into overdrive after the discovery of radium.

Radium, often found as an impurity in sources of uranium, was itself used in paints, as it had the lovely effect of glowing in the dark. Since tons of uranium had to be procured to get small amounts of radium, there was a lot of uranium lying about. Artists and factories making glass and pottery soon put it to use. Although the risk from the radiation in uranium-pigmented objects is low, it is very rarely used today.

8 Han Purple

Even old-fashioned pigments can have interesting things to teach us today. Han purple and the closely related Han blue (both of which are used in the mural above) were pigments created by the ancient Chinese 2,500 years ago.[3] Han purple was used to paint murals, decorate the famous Terracotta Warriors, and to produce glass. The use of Han purple stopped in the third century AD and was forgotten until it was rediscovered in the 1990s.

Blue and purple are hard pigments to make from natural materials. Han purple is created by mixing ground quartz, a barium mineral, copper, and lead salt together in precise proportions and heating them to around 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,800 °F). Given the heat and ingredients used in its creation, it seems likely that Han purple was a by-product of glass manufacture, but how it was invented will likely always be a mystery.

Its creation is less interesting to some than the properties it is showing today. It has been discovered that when Han purple is cooled to just above absolute zero and a magnetic field is applied to it, it becomes first a superconductor and then a Bose-Einstein condensate. It’s as if Han purple loses a dimension under these conditions, and electrons flow in only two dimensions.

7 Cochineal

Humans generally tend to dislike eating insects, unless those insects make their food a pretty color. Cochineal, or carmine, or natural red 4, is produced by a tiny insect that lives on a variety of cactus. The females of the species feed on the red berries of the cactus and produce an intense red chemical.

When Europeans reached Mexico, they found that the natives were able to produce a red cloth far more vibrant than anything they had seen before. Soon, cochineal became a highly sought-after dye, and for more than just clothing.

The process of harvesting the insects is a delicate and time-consuming one.[4] Once harvested from the cacti, the bugs are rolled around on a wooden board to kill them without damaging the valuable pigment, and they are then left out to dry in the sun. 70,000 insects are required to make a single pound of cochineal.

While synthetic reds replaced cochineal in clothing manufacture, it is still sometimes used in the food industry to color foods and drinks, especially in brands that want to boast about only using “natural ingredients.” In 2012, Starbucks decided it would no longer use cochineal after an outcry from consumers.

6 Scheele’s Green

Some colors are just to die for, and Scheele’s green might just kill you. Made from copper and arsenic, Scheele’s green was hugely popular in the 19th century and featured in everything from wallpaper, to clothes, to food. A fondness for representing the natural world indoors meant a strong green dye was needed, and Scheele’s green was just waiting to be used.

One problem was that people who used Scheele’s green to make things tended to get sick, really sick. Workers inhaled the arsenic-laden dust or got it on their fingers. Many were lucky to escape with open sores, while others wasted away from chronic arsenic poisoning.

The use of Scheele’s green in wallpapers created deadly rooms. When the wallpaper got damp, or fungi grew on it, arsine gas was produced. It may have played a role in the death of Napoleon, who, in exile on Saint Helena, thought his British guards were trying to poison him. He did have many of the symptoms of arsenic poisoning, but it may not have been the British who killed him. He had wallpaper of a very lovely green color.[5]

5 Vantablack

It is a common joke that carbon nanotube technology is ten years away from changing the world . . . just like it was ten years ago. There have been a number of fascinating, if limited in scope, uses of carbon nanotubes, but perhaps the most eye-catching is Vantablack. Well, perhaps it’s not eye-catching because your eyes tend to slide right off objects coated in this black pigment, which is the darkest substance made by man.[6]

Vantablack is not a pigment in the usual sense, in that you cannot just paint it on an object. It is created by aligning nanotubes on a surface in a certain way so that almost all the light hitting the surface is absorbed. It is certainly a startling effect, and that is why it has been sought after by many artists.

Unfortunately for other artists, British artist Anish Kapoor managed to get exclusive rights to the use of Vantablack in art. This monopoly on the use of the material did not sit well with many people. So when Stuart Semple created what he called “the pinkest pink,” he offered to sell it to anyone—except Anish Kapoor, who was already hogging the “blackest black.” Buyers had to agree to a legal declaration stating, “You are not Anish Kapoor, you are in no way affiliated to Anish Kapoor, you are not purchasing this item on behalf of Anish Kapoor or an associate of Anish Kapoor.”

When Kapoor did get his hands on a sample of the pink, he dipped his middle finger in it and posted it to Instagram.

4 Dragon’s Blood

What could be cooler than painting with dragon’s blood? Fortunately for ancient artists, there was no need to go out and slay dragons to get it. Unfortunately, the only sources for the pigment were plants that often grew thousands of miles away.

Dragon’s blood comes from a range of plants and is the red-colored resin that they produce when damaged. One of the sources of dragon’s blood for the Romans was the island of Socotra off the coast of Africa in the Arabian Sea. This island is home to many bizarre-looking plants and animals. When the dragon’s blood tree is cut, it looks as if it is bleeding. Despite the intense red of the resin the trees produce, the red pigment in it, dracorubine, makes up only one percent of the fluid.[7]

The ancient Romans found it hard to tell the difference between dragon’s blood and another red pigment called cinnabar. Since cinnabar is a compound made with mercury, it often soon became apparent which was which, as people who used cinnabar often fell ill with chronic mercury poisoning.

3 Oak Gall Ink

Making books used to be a long and expensive process. In the Middle Ages, people making a book wanted it to last, so they used animal skins, called parchment, instead of paper. Unlike paper, skin is not absorbent, so if you want to write on it, you have to create an ink that will both stick to the parchment and last a long time.

Somehow, oak gall ink (also called iron gall ink) was invented. The process of making it involves finding an oak tree that has been attacked by parasitic wasps. These wasps lay their eggs on the tree and force it to create little hard balls, called galls, where their eggs develop. These galls are then smashed to powder and left to stew in water for several days. The resulting brown liquid is mixed with an iron-containing compound that creates a black ink. To get this to stick to the page, a gum has to be added, too.

Even today, recreating oak gall ink can be tricky.[8] Made incorrectly, it can flake off the page, leaving you with nothing but an expensively bound book of leather.

2 Indian Yellow

Indian yellow is not a simple pigment like many on this list. Instead of being a single chemical, it is composed of a range of chemicals, but this is only to be expected, given its source. When seen under sunlight, the yellow it produces is particularly luminous, as it fluoresces slightly. Some, however, thought that the pigment had an unpleasant smell, which, again, may be due to its source—cow urine.

Also known as purree, the pigment originated in India in the 15th century. It was made by feeding cows a special diet of mango leaves and letting them urinate onto a special sand. When the lumps of sand and dried urine were collected, they were ground to make the pigment. European artists loved the vivid yellow, and many famous works of art, including the stars of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, used it.

The artists themselves did not know what it was they were painting with. Indian yellow fell out of favor partly because of an investigation into its manufacture in the early 20th century.[9] It was found that the diet of mango leaves fed to the cows left them very unhealthy. The practice was eventually banned.

1 Mummy Brown

Egyptian mummies are one of our best ways of learning about the past. As well as teaching us about the Egyptian funerary rites, they can tell us about the health of individuals, their cultural status, and much more. Even the wrappings used on the mummies can be revealing, as old texts were often used. Otherwise, lost works from the ancient world are still being recovered from mummies. Besides this, they are the physical remains of a once-living person, which makes it all the more tragic that thousands of them were unceremoniously ground up to make a pigment known as mummy brown.[10]

Artists loved the tone of the pigment because it gave them a new color to capture the dark wood used inside homes at the time. But when it was discovered what the source was, some were deeply disturbed. Edward Burne-Jones is said to have given his tube of mummy brown a burial in the garden as soon as he found out what it was made from. Others were less squeamish. Martin Drolling supposedly used the corpses of disinterred French kings to make his own pigment.

Despite the moral issues of using mummies for paint, the practice only stopped in 1964, when the supply of mummies ran out.

Read more colorful facts on Top 10 Strange Mysteries And Facts About Color and 10 Amazing Ways Colors Have Been Significant In History.

![10 Abandoned Amusement Parks With Horrific Histories [Disturbing] 10 Abandoned Amusement Parks With Horrific Histories [Disturbing]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/gulliver-150x150.jpeg)