History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Notable Child Soldiers Of The United States Civil War

Both the Union and the Confederacy enlisted child soldiers during the bloody US Civil War that lasted from April 12, 1861, to May 9, 1865. Many of the children served with distinction and returned home. Others were not so lucky and paid with their lives.

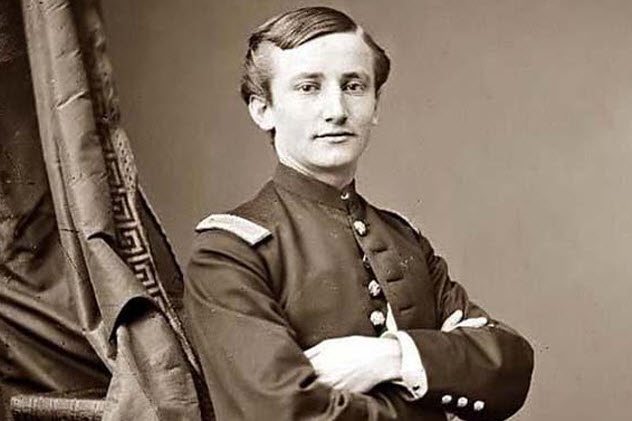

10 Edwin Francis Jemison

The portrait of Confederate Private Edwin Francis Jemison is one of the most famous photographs of the Civil War. He was born on December 4, 1844, and enlisted in the Confederate 2nd Louisiana Infantry in May 1861 when he was 16. The photograph for which he is remembered was taken soon after his enlistment.

Edwin’s first encounter with the Union Army was in April 1862 when his unit faced enemy troops in the Battle of Dam No. 1 in Virginia. His second encounter was in the July 1, 1862, Battle of Malvern Hill, which remained the deadliest battle of the Civil War until it was superseded by the Battle of Antietam.

The Confederates lost about 5,500 soldiers during the battle while the Union lost half of that number. Jemison became part of the Confederate casualty list when he was hit by a cannonball while charging toward Union lines.[1] He was five months to clocking 18.

9 John Lincoln Clem

John Lincoln Clem was born John Joseph Klem, but he swapped “Joseph” for “Lincoln” in reverence for President Abraham Lincoln. In 1861, at age 10, John fled from home to join the Union 3rd Ohio as a drummer.

The 3rd Ohio turned him down for being underage, and he left to join the 22nd Michigan, which turned him down for the same reason. Undeterred, he tagged along with the 22nd Michigan, which later adopted him as a mascot and drummer, although he was only allowed to enlist in 1862.[2]

John Clem swapped his drum for a musket during the September 1863 Battle of Chickamauga, where three bullets pierced holes in his hat. He strayed from his unit during the battle and was spotted running back to his lines by a Confederate colonel who chased after him and demanded his surrender.

Rather than surrendering, he shot and killed the colonel, who had referred to Clem as a “Yankee Devil.” The incident earned him a promotion and the nickname “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga.” He was discharged from the army in 1864. But he rejoined as a second lieutenant in 1871 and retired as a brigadier general in 1915.

8 Elisha Stockwell

Elisha Stockwell first enlisted in the Union Army during a recruitment drive in Jackson County, Wisconsin, when he was 15. His father disapproved of his enlistment, which caused the recruiters to remove Elisha’s name.

Undeterred, he fled with a Union soldier who was a friend of his father and had come home on leave. Before taking off, Elisha visited his sister and told her he was going downtown. She told him to return early for dinner.

Elisha did, two years later.

During his second enlistment, he told the recruiter that he could not remember his age although he thought he was 18. The recruiter knew Elisha was younger than 18. Still, the man listed Elisha’s age as 18 and his height as 165 centimeters (5’5″)—a height he only reached two years later.

Elisha saw a dead man for the first time in the 1862 Battle of Shiloh when he stumbled on a dead, disemboweled soldier with his back to a tree. According to Elisha, the encounter made him “deadly sick.”

He also saw his first action in that battle when he joined a downhill charge toward Confederate lines. When the charge was called off, half the men in his unit were either dead or wounded.

For the first time, Elisha realized that his decision to run away from home was foolish because warfare was no joke. He returned home after the war to learn that only three (including him) of the 32 men and boys from his hometown who had left for the war had lived.[3]

7 William Johnston

William Johnston is the youngest recipient of the Medal of Honor. He was born in July 1850 and enlisted in the Union 3rd Vermont Infantry as a drummer in May 1862.

He participated in the “Seven Days” battle that lasted from June 25 to July 1, 1862, in which his unit was forced to retreat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s forces. Confederate troops followed and fired at William’s unit as it retreated, forcing many soldiers to dump their weapons and drums.

Only William had his drum when the entire division, which included the 3rd Vermont Infantry, was mustered for an Independence Day parade on July 4. So he played for the entire division.

President Abraham Lincoln was so impressed with William’s resolve to hold onto his drum when the older soldiers dumped their weapons and drums that Lincoln awarded William the Medal of Honor. At age 13, William is the youngest recipient to date.[4]

6 John Cook

John Cook enlisted in the Union 4th United States Artillery as a bugler when he was 15. He participated in the deadly Battle of Antietam where his battery was attacked by Confederate infantry.

His battery suffered about 17 wounded or dead during the first wave of the assault. The wounded included the commander, Captain Campbell, whose horse was killed. Injured survivors were targeted by enemy fire as they attempted to retreat to the rear, but John managed to drag the captain back there before returning to commandeer a cannon.

He was joined by the division’s commander, Brigadier General Gibbon, who loaded and fired the cannon like a regular soldier. Meanwhile, the Confederates made three unsuccessful attempts to capture the cannons.

The third attempt was the most dramatic as they got within 3–5 meters (10–15 ft) of the cannons. At the end of the fight, the battery had 44 men and 40 horses dead or wounded.[5] John Cook was awarded the Medal of Honor for his efforts, making him the youngest artillery soldier to ever earn such a distinction.

5 Robert Henry Hendershot

Robert Henry Hendershot was 10 when he joined the Union’s 9th Michigan Infantry as a volunteer drummer in 1861. He took the drumming craft with unusual seriousness for an ill-mannered rascal who regularly fought with his mother and skipped school to pelt train passengers with fruits.

However, he was only allowed to enlist in the unit in March 1862. It was from this moment that his accounts of the war became divided between truths, exaggerated truths, and outright lies.

He reportedly killed a Confederate colonel during a siege in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where he was captured and freed during a prisoner exchange. He reenlisted in the 8th Michigan as Robert Henry Henderson on August 19, 1862, but found his way into the 7th Michigan instead. There, he claimed to have taken the surrender of a Confederate soldier in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Trouble started in August 1891 when veterans of the 7th Michigan denied that Robert was ever in Fredericksburg. They stripped him of the title “The Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock” and claimed that the real drummer boy was either John T. Spillaine or Thomas Robinson.[6]

Meanwhile, the 8th Michigan claimed that it was Charles Gardner. Robert only got his title back after several notable people, including President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant, intervened.

4 Charles Edwin King

Charles Edwin King holds the record of being the youngest fatality of the Civil War. He was born on April 4, 1849, and enlisted as a drummer in the Union’s 49th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers on September 12, 1861. He was 12 years old. His father opposed his enlistment but gave in on the assurance of Captain Benjamin Sweeney, who promised to keep Charlie away from the front lines.

Charlie first saw action in the Battle of Williamsburg, where the Union Army was routed from the Virginia Peninsula by Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s troops. Charlie saw combat again in the September 17, 1862, Battle of Antietam, which remains the deadliest battle of the Civil War.[7]

Estimates vary, but the casualty rate is believed to be at least 22,720 troops: 12,400 from the Confederate side and 10,320 from the Union. This doesn’t include civilians who died of disease after the battle and the 6,300 soldiers who died in a prelude to the battle three days earlier.

The battle would also be Charlie’s last as he was seriously wounded when shrapnel from a Confederate shell exploded close to him at the rear lines. The shrapnel passed through his body, causing extensive injuries that turned fatal three days later. He died on September 20, 1862, at age 13.

3 Frederick Grant

At age 12, Frederick Grant, the son of Union General Ulysses S. Grant, followed his father to war. Frederick camped in his father’s tent and was allocated his own horse and uniform. General Grant barred the boy from visiting the front lines, but he still did, at least until a Confederate soldier shot him in the leg.

Frederick’s low point of the war was the Battle of Port Gibson, where the Union suffered 131 dead and 719 wounded. Frederick visited the battlefield after the fighting and helped to gather the dead. This horrendous task made him sick, and he quickly left to join other soldiers bringing the wounded to a makeshift hospital. The sight at the hospital was worse, and the horrified boy left to sit by a tree.[8]

A report by someone else who also visited this hospital after the battle stated that its yard was filled with a heap of amputated arms and legs. According to the person, seeing that was worse than seeing dead people, as it evoked in him very deep feelings he had never felt before.

2 Edward Black

Edward Black enlisted in the Union 21st Indiana Infantry as a drummer at age eight, making him the youngest person to ever serve in the United States Armed Forces. Like other drummers, Edward was always at the front, where he played his drums to lead and direct the troops. This made him and other drummers perfect targets for enemy soldiers willing to disorganize the unit.

Edward was captured during the Battle of Baton Rouge and imprisoned on an island in the Gulf of Mexico. But he regained his freedom when Union forces captured the island and nearby New Orleans.

After President Lincoln banned the use of child soldiers in 1862, Edward was discharged and returned to his Indianapolis home with his drum. However, the trauma and injuries he sustained during the war haunted him so badly that it probably contributed to his death at age 18. His drum currently sits at The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis where it remains one of the museum’s most prized artifacts.[9]

1 Abel Sheeks

Abel Sheeks fled his Alabama home to join the ranks of the Confederate Army when he was 16. With the Confederates short on uniforms, Abel had to wear his blue shirt and trousers (which resembled the Union’s uniform) into battle. That continued until a colleague asked if he wanted to be mistaken for a Union soldier.

After each engagement, Abel scoured the battlefield to scavenge uniforms from dead Confederate soldiers of his size. According to him, he hated doing it but was left with no choice. In a few weeks, he had a full Confederate uniform.

Training for military life was hell for the boys at the Confederate camps. Drills were the centerpiece, and shooting practice was almost nonexistent because guns and ammunition were in short supply. This meant that many Confederate soldiers received their shooting lessons right on the battlefield.[10]

Drills at the Union camps were no better. One Union boy who had endured enough of the boring, repetitive actions during his first drill told the drill sergeant, “Let’s stop this fooling and go over to the grocery.” The drill sergeant did not take kindly to his suggestion and ordered a corporal to “drill him like hell.”

Oliver Taylor is a freelance writer and bathroom musician. You can reach him at [email protected].

Read more about the wartime exploits of children on 10 Armies That Sent Children Into Battle and Top 10 Remarkable Teenagers Of World War II.