Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

10 Reasons Why Life Sucked In The 19th Century

People pine for the good old days, when humans somehow lived better, more fulfilling lives than they do today. The sad fact is that there were never any “good old days.” The only thing that has changed over time is our ability to express compassion for other living beings and the safety measures that we have put in place to help protect lives.

As a whole, we’ve forgotten what life was really like long ago. The 1800s, for example, were dangerous times when disease and lack of education could kill the innocent, the vulnerable, and even the strongest among us. Life was fragile, and death was always right around the corner.

10 Mangled By Machinery

Working in the mills and factories before the age of safety regulations was deadly. Newspapers reported numerous instances of women, children, and men being mangled by exposed machinery.

Most of the accidents could have been prevented with appropriate clothing and safety barriers. For example, a young Wisconsin woman was inspecting the machinery in a flour mill in 1861 when “her clothing came in contact with an upright shaft.” She could not break free, and by the time word got out to shut down the mill, her body was “horribly mangled.”

In a report published in 1892, we learn that a young man was ground to death in a California paste factory. When he began to fix the “dough,” the wheel inside the paste tub spun and caught his hand. He was pulled in between the tub and the grindstone, where he was ground to death.[1]

9 Strychnine Ale

Strychnine was considered a tonic in the 1800s and was used as such well into the 20th century. It was also added to beer, in small amounts, of course, as a flavoring. However, there were plenty of instances where too much strychnine was used, and the beer drinkers would become sick and sometimes die.

Such was the case in 1880, when two men ordered some beer in Prahran, Victoria, Australia. A bottle of ale was obtained from a store owner, and the men poured it into two glasses. When they took a drink of the stuff, it proved to be too bitter to finish off. Soon afterward, the men began to feel sick and showed signs of strychnine poisoning. They were taken to the hospital, and under good medical care, they survived the poisoning. When the brewer was informed of the incident, he was able to remove all bottles of his ale from the stores, thus preventing any more poisonings from the bad batch.

In 1892, Catherine Waddell of Maryborough, Queensland, was not so fortunate. After drinking a small quantity of very bitter ale, she panicked. She believed she had been poisoned by strychnine and shortly died.

A postmortem examination convinced a doctor that the silly woman had died from fear, and the case might have been dismissed if law enforcement hadn’t collected the bottle of ale. It was found to contain the equivalent of 12 grains of strychnine. A half-grain of strychnine was enough to kill a healthy person, so the deceased woman was not wrong when she announced that she had been poisoned.

Further investigation into her death showed that the bottle had not been properly washed at the brewery and that it must have had the strychnine residue in it when the ale was bottled.[2]

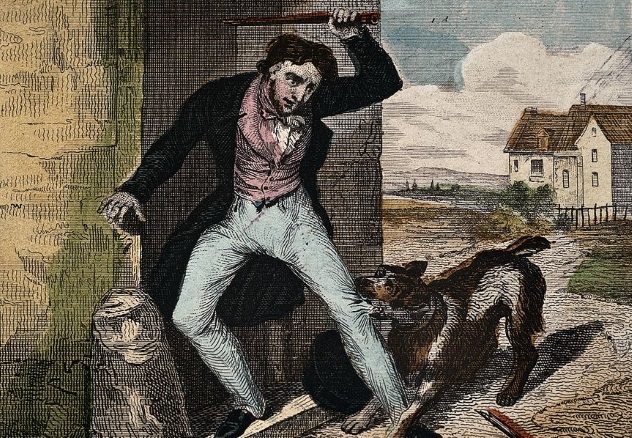

8 Hydrophobia: Not Real

Hydrophobia and rabies were often used interchangeably during the 1800s, but what is most fascinating about this deadly disease is that there were doctors during this time period who believed that there was no such thing as hydrophobia. For example, in 1897, a paper was read by Dr. Irving C. Rosse before the American Neurological Association, and the doctor “did not hesitate to speak of hydrophobia as a purely imaginary disease, with no more realty to rest upon than . . . witchcraft . . . ”[3]

In spite of the doubt as to the existence of rabies, cases were being reported in the newspapers, especially when it came to pets and wild animals. By 1899, doctors were publishing articles once again, assuring the public that hydrophobia was indeed a real disease and that it could be spread from animal to animal and animal to man.

It is not known how many people died from rabies simply because so many doctors did not believe that the disease actually existed.

7 Drowning Dogs

An article published in a Wisconsin newspaper in 1876 gave the following description of “healthy” boys in nature:

The boy is a part of Nature. [ . . . ] He uses things roughly and without sentiment. The coolness with which boys will drown dogs or cats, or hang them to trees, or murder young birds, or torture frogs or squirrels, is like Nature’s own mercilessness.

With this attitude, it is little wonder that drowning dogs was a common method for getting rid of abandoned or lost pets.

The local dog catcher of Saint Paul, Minnesota, announced in 1893 that he was no longer going to kill unlicensed dogs with “charcoal gas.” Instead, he was going back to drowning them.[4] The US wasn’t the only country drowning unwanted dogs. It was reported in 1891 that stray dogs found in South Brisbane would also be drowned.

6 Infanticide

A Melbourne newspaper published an article in 1897 asking what the government could possibly do to stop the growing trend of killing unwanted babies.[5] Whether it was family members murdering the infants or their lives being taken by the baby farms, something certainly had to be done because the bodies of babies were being discovered at an alarming rate on land and in water.

In 1873, a young boy fishing in Tasmania got his line caught on something. He struggled with it and eventually pulled up a wooden box held together by a bit of chain. When opened, the body of an infant was discovered inside.

Three infants were discovered in New South Wales in 1887 inside a single day. The first body was less than a week old and was wrapped in shirting before being left in the roadway. The second body was that of a five-day-old female, left in a paddock. The third infant was a newborn male, left on a vacant lot. All three of the infants had either string or tape wrapped around their necks to cut off their air supply. Fortunately, the third infant was still struggling to breathe when he was found and was immediately revived and taken to a hospital.

5 The Grinning Death

Lockjaw, more commonly known as tetanus, was not a preventable disease until the early 20th century. Before the invention of the vaccine, people died horrible “grinning deaths” when the tetanus bacteria entered their blood stream. Victims of lockjaw would be overcome with vicious muscle spasms and seizures, until death gave them mercy.

A lockjaw epidemic was reported in the summer of 1899 in New York. Between July 4 and July 22, there were 83 deaths from the disease, caused by “careless handling of fireworks and toy pistols.”[6] The mortality rates at that time were anywhere from 85 to 90 percent, meaning that anyone who was punctured by contaminated material was highly likely to die.

Doctors were searching for a cure for the disease, but it was with little success. One doctor in Tours, France, reported that “the symptoms of tetanus were relieved immediately by nerve stretching,” but the patient died a few hours after the ordeal.

4 Swallowing Pins

Women kept a large assortment of pins handy in the 19th century. While mending clothes, they would often hold the pins in their mouths, leading to numerous reports of people accidentally swallowing them. For example, in 1897, a 56-year-old housemaid swallowed a brass pin. She was taken to the hospital but died six weeks later after the pin had perforated her intestines.

Children were also victims of pin swallowing, but the subject was treated almost nonchalantly in newspaper reports. For example, in 1881, it was reported that a boy just coughed up a pin he had swallowed six years previously.

In another case, also reported in 1897, an infant swallowed an open brass safety pin. The parents watched over him for the first few days but quickly forgot about the whole thing until six months later, when their boy started coughing. When the baby was picked up, “he coughed up considerable blood, and with it came the long looked for pin. The pin was badly corroded and blackened.”[7]

3 Carcasses Dumped Into Bay

New York City had a tremendous problem with animal carcasses, as reported in 1870. The New York Rendering Company and other contractors would collect the bodies of cats, dogs, horses, and the remnants left over from the butcher shops and dump them all into the Lower Bay. There were so many dead animals that they were washing up on the shores. Tenants who lived along the Hudson River were getting sick. At any time, up to 15 dead horses could be seen floating, bloated, in the water.

People started to complain about the awful smell and gruesome sights. It was then decided that the carcasses had to be dumped outside the city limits, but they continued to wash up on shore, and “Gothamites who go down the bay for a sail often [had] a very disagreeable experience of dead horse odors after they [returned].”[8]

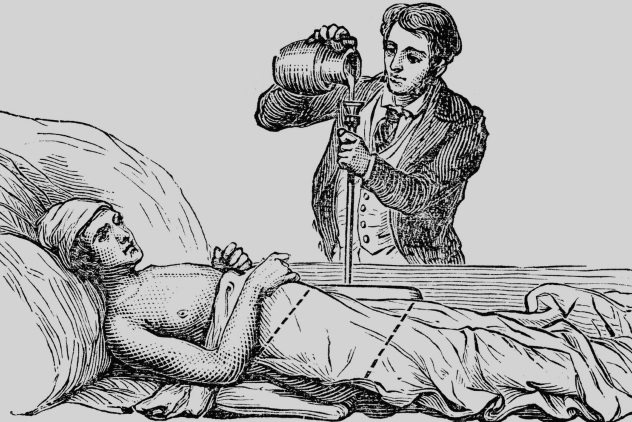

2 Gruesome Experiments On People And Animals

There was very little oversight when it came to medical experiments in the 19th century. Both people and animals, either voluntarily or involuntarily, were used in prodecures that we would rightly view as cruel or gruesome by today’s standards.

In 1893 in France, a 45-year-old woman suffered from “a tumor in the frontal bone.” Her doctor had to cut open her skull and remove the tumor. He was then faced with the problem of what to use in place of the original skull bone. As part of a novel experiment, he had a piece of skull bone removed from a living dog and, “taking antiseptic precautions,” fitted it into the woman’s head.

In 1889, there was also a growing experimental trend of injecting people with “matter from certain glands of the lower animals.” This was done to increase vitality in aging people.

Animals were at the mercy of medical doctors. While in some countries, there were laws against certain cruelties to animals, it was still being decided if the laws should apply to doctors.

In one case that went to trial in 1888 in Victoria, Australia, a doctor was experimenting on dogs. He would make an extract from meat and inject it under the dogs’ skin. His goal was to see if dogs could forego ingesting food through the stomach. The dogs were given as much water as they wanted, and the doctor claimed that the dogs were not experiencing any pain.

At the close of the trial, it was decided that although some cruelty had been inflicted on the dogs, the bench could not determine the exact extent of the suffering involved. The doctor was told to register and pay fees to continue his experimentation on animals.[9]

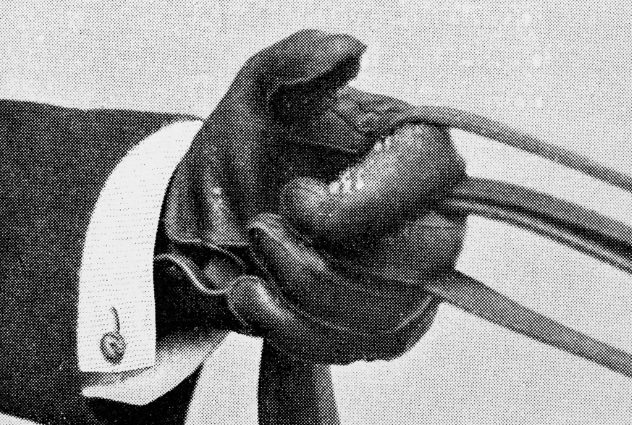

1 Wearing Items Made Of Human Skin

Wearing gloves or belts made of human skin is something that would make most of us shudder, but it was actually quite common long ago. An article published in 1899 tells us that the skin was taken from the bodies of the poor who were not claimed by friends or relatives when they passed on.

Unclaimed bodies were often handed over to the medical schools, where they were dissected. Medical students would then collect the skin and sell it to tanners and jewelers. There was a high demand for items made of human skin in the United States, and the skin sold for a good price because it was in short supply.

Perhaps one of the more gruesome stories of wearing leather from human skin was published in 1888. A physician living in New South Wales had his shoes made from the skin of Africans. According to him, Africans made the softest and most durable leather.

The man had no ill feelings toward Africans and was a foreign-born US citizen who fought in the Civil War to free African Americans from slavery. In his own words, “I would use a white man’s skin for the same purpose if it were sufficiently thick and if anyone has a desire to wear my epidermis upon his feet after I had drawn my last breath, he has my ante-mortem permission.”[10]

Elizabeth, a former Pennsylvania native, recently moved to the beautiful state of Massachusetts where she is currently involved in researching early American history. She writes and travels in her spare time.

For more dangers from the 1800s, check out 10 Dangerous Beauty Trends From The Victorian Era and 10 Deadly Street Gangs Of The Victorian Era.