Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

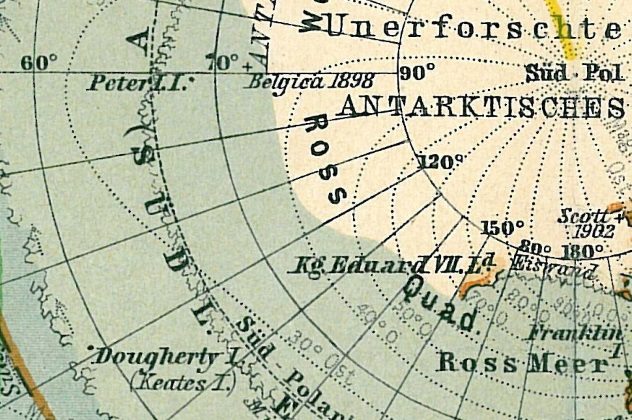

Top 10 Nonexistent Islands That Appeared On Maps

There are certain islands that have been “discovered” and added to maps before being found to be nonexistent. Yet, their discoverers often claim to have sighted them, and some even said they landed on them. Expeditions sent to the supposed locations of these islands often ended up finding the open ocean and nothing else, although some claimed to have found the islands.

We have complied ten such islands. This list does not contain islands deliberately added to maps to catch plagiarists, similar to trap streets.[1] All the islands were actually reported to have been spotted, though some were made up. However, they all appeared on maps.

10 Sandy Island

Sandy Island was only found not to exist in 2012. Before then, it appeared on several maps, including Google Earth, where it was positioned between Australia and the French-governed New Caledonia in the Pacific. The island was first recorded by the British whaling ship Velocity in 1876 and first appeared on a British map in 1908.

Several expeditions failed to find the island, and it was removed from some maps in the 1970s. However, it remained on other maps. Curiously enough, the island does not appear on French maps, which means that the French either knew about its nonexistence or were ignorant of its supposed existence. If the island really existed, it would have belonged to France, since it was in French waters.

The nonexistence of the island was proven by scientists from the University of Sydney, who decided to visually confirm its existence after they realized their charts showed the supposed location of the island to be 1,400 meters (4,600 ft) deep. It is believed that the crew of the Velocity saw a pumice raft, which they mistook for an island. Pumice rafts are floating rocks formed by volcanic activity. They are known to float past the area where Sandy Island was supposedly located.[2]

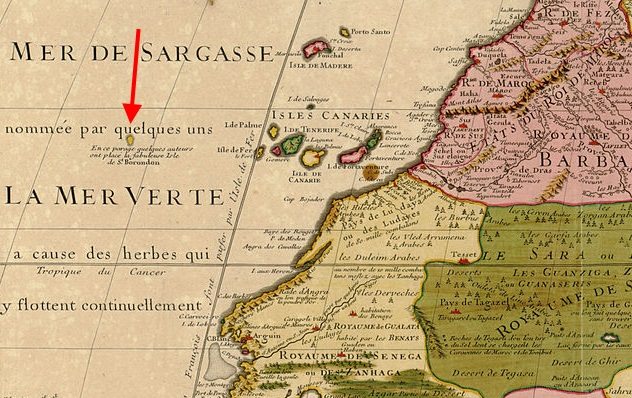

9 Saint Brendan’s Island

If ancient maps were correct, Saint Brendan’s Island (or Isle) is supposed to lie west of the Canary Islands and south of the Azores in the North Atlantic. The island is named after Saint Brendan, an Irish monk who claimed to have found it in AD 512. Saint Brendan didn’t just find the island. He and 14 monks landed on it and even lived there for two weeks.

A monk called Barino even described the island, stating it was covered with mountains, forests, birds, and flowers. Other expeditions searched for the island to no avail, and by the 13th century, it was evident that it did not exist. Marcus Martinez, a Spanish historian, even described it as “the lost island discovered by St. Brendan but nobody has found it since.”

However, another sailor claimed to have found it in the 1400s but couldn’t land because of bad weather. This renewed interest in the island, and the king of Portugal sent out some ships, but they never returned. Saint Brendan’s Island continued appearing on maps, and ships continued looking for it until the 18th century, when everyone finally agreed that it didn’t exist.

According to a website called Journal of the Bizarre, Saint Brendan’s Island really existed. However, it has been submerged and is now under the ocean. There might be some truth to this, as an underwater mountain called the Great Meteor Seamount lies under the sea where the island is supposed to be.[3]

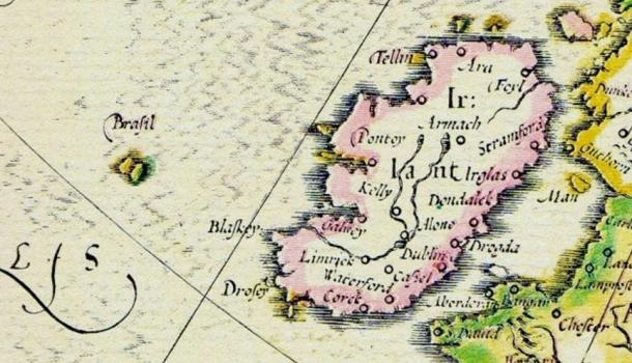

8 Hy-Brasil

Hy-Brasil is a nonexistent island said to be about 320 kilometers (200 mi) off the western coast of Ireland. Some maps even represented it as two islands, although they shared the same name. The island first appeared on maps in 1325 and appeared in maps made until the 1800s, when its supposed existence was declared a hoax. The island also has its fair share of myths.

Europeans believed it contained an advanced civilization, while the Irish said it was obscured by a heavy mist and was only visible once every seven years. The name, shape, and location of the island frequently changed on maps, even though it remained in the same region. England sent three expeditions between 1480 and 1481, but none found the island. However, in 1497, a Spanish diplomat stated that one of the English expeditions found Hy-Brasil.

In 1674, a Scottish sea captain named John Nisbet claimed to have spotted the island as he sailed from France to Ireland. He claimed four of his man landed on it and remained there for a whole day. The veracity of Nisbet’s claims remains in doubt, for he further claimed that the island was inhabited by an old man who gave them gold and silver and a magician who lived in a castle.

Captain Alexander Johnson launched a follow-up expedition and also claimed to have landed on the island, although he didn’t mention whether the old man gave him gold. In 1872, Robert O’Flaherty and T.J. Westropp also claimed to have sighted Hy-Brasil. Westropp even claimed he visited it thrice, including one occasion when he took his family along. He claimed they saw the island appear and disappear.[4]

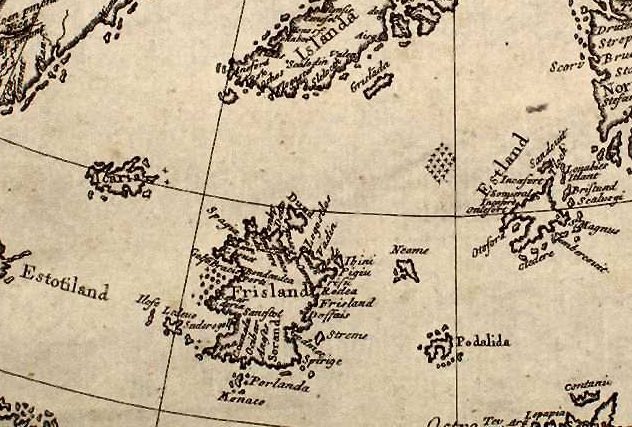

7 Frisland

In 1558, Nicolo Zeno from Venice claimed that two of his ancestors, Antonio and Nicolo, discovered an island called Frisland in the 1380s. Zeno claimed the island was south of Iceland, with Norway to its east and Estotiland in the west. Estotiland itself would have been either Newfoundland or Labrador in North America. If that was so, it means Zeno’s ancestors reached America before Columbus.

It is believed that Zeno faked the existence of Frisland because he wanted to be popular. And the Venetians swallowed his lies hook, line, and sinker because they wanted their navy to remain relevant, as it was being thrown into obscurity by the prominence of the navies of Spain, France, and England.

Frisland appeared on several maps until it was declared to be a hoax in the 19th century, but not before several sailors claimed to have sighted it. In 1576, Englishman Martin Frobisher mistook Greenland for Frisland, and John Dee even claimed it for England in 1580.[5] Then, in 1989, Giorgio Padoan, a philologist (who studies historical writings), claimed Zeno was telling the truth and that the Italians reached the New World before Columbus.

6 Buss Island

Buss Island is a nonexistent island that was supposedly located between Ireland and the nonexistent Frisland. It was discovered by Martin Frobisher, who, as we already mentioned, mistook Greenland for Frisland. In 1578, he probably mistook another island for an undiscovered island, which he named Buss Island.

Captain Thomas Shepard claimed to have visited and mapped Buss Island in 1671, causing England to send an expedition. The expedition failed to find the island. More expeditions were sent to find the fabled Buss Island, but none succeeded in finding it, even though ships that weren’t looking for it always claimed to have found it.

In 1776, it was reported that the location of the supposed Buss Island was shallow, which made some believe it had sunk. It was even renamed the Sunken Land of Buss. However, an expedition by John Ross in 1818 revealed that the alleged location of the island was not shallow. Buss Island continued to appear on maps until it was expunged in the 19th century.[6]

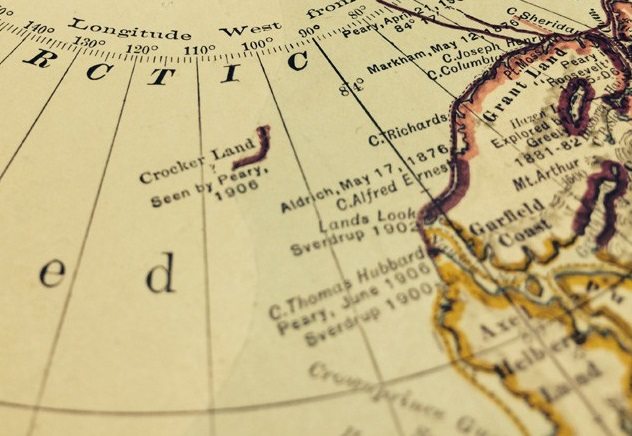

5 Crocker Land

Like Frisland, Crocker Land is another island that was completely made up. This time, it was by Robert Peary, who was trying to raise funds for an expedition to the Arctic. In 1907, Peary claimed to have discovered a new island around Greenland, 209 kilometers (130 mi) northwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard in Northern Canada, during an earlier expedition in 1906.

He named the island Crocker Land, after George Crocker, who had co-sponsored his 1906 expedition to the tune of $50,000. Peary wanted another $50,000 from Crocker, which was what the fake island was all about. Peary even wrote a book titled Nearest the Pole, in which he talked about his fictitious island. Everyone believed him, and several explorers even started looking for the island.[7]

Crocker Land remained elusive, which led some to call it “the Lost Atlantis of the North.” However, it appeared on Arctic maps created between 1910 and 1913. This new land, which was even called a continent in some quarters, generated widespread interest, especially in the United States, until it was exposed as a creation of Peary.

4 Dougherty Island

Some call it Dougherty’s Island, but it doesn’t matter because it doesn’t exist. Dougherty Island was named after Captain Daniel Dougherty, who “discovered” it far south in the Pacific Ocean during a trip from New Zealand to Canada in 1841. Several other sailors also confirmed its existence, but one Captain Scott couldn’t find it when he passed by its supposed location in 1904.

On August 11, 1931, The Sydney Morning Herald of Australia reported that a joint British, Australian, and New Zealand expedition sailing to Antarctica passed by the supposed location of Doherty’s island and couldn’t find it.

The details of the incident were noted by the commanding officer of the ship, Captain Mackenzie, who stated that the vessel passed directly above where the island was said to be. The weather was clear, and there was no island within a 19-kilometer (12 mi) radius, so it couldn’t have been somewhere else. Dougherty Island was removed from British maps in 1937.[8]

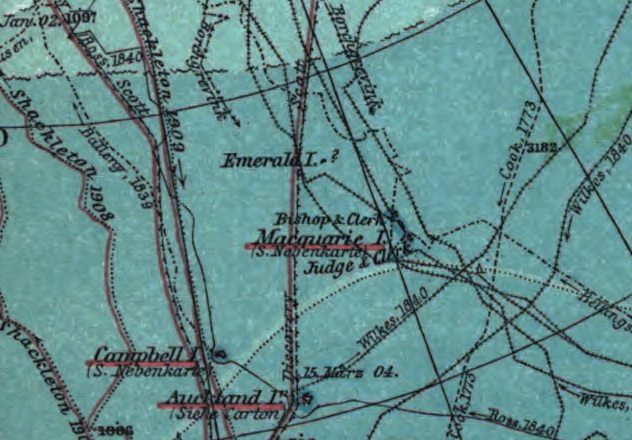

3 Emerald Island

In 1821, Captain Nockells spotted an island south of Macquarie Island and close to Antarctica. He named it after his ship, the Emerald. Emerald Island seemed to have a preference for determining whoever sees it, since it supposedly appears and disappears at will. Some expeditions claimed to have sighted the island, while others reported that they couldn’t find it. Some even say it moves around, which is why people cannot see it at its supposed location. Others say the island really existed but has been submerged due to seismic activitiy.

Those who claim to have seen the island cannot agree on what it looks like. Some say it is mountainous with steep cliffs, while others say it is hilly with green forests. In 1890, one captain even said it was small and full of rocks with no suitable place to land.

In 1840, two ships commanded by Commodore Wilks of the United States passed over the supposed location of Emerald Island and found nothing. Captain Soule also passed over the alleged area of island in 1877 and found nothing. Shackleton and Amundsen passed by where the island should have been in 1909 and 1910 and also found nothing.

However, two interesting incidents occurred around the claimed location of the island in 1894 and 1949. In 1894, a Norwegian expedition to the South Pole spotted what they thought was the island. However, it ended up being an iceberg. HMNZS Pukaki of the Royal New Zealand Navy also spotted the island in April 1949. Getting closer, the crew discovered that the supposed island was actually a group of clouds that appeared to be on the water.[9]

2 Isle Of Demons

In 1542, Jean-Francois de Roberval, the lieutenant-general of New France (now Canada) left the shores of France for New France with three ships. With him was his cousin, Marguerite de la Rocque, who he marooned with her lover and her maid on the Isle of Demons, which was supposedly located on Quirpon Island in today’s Newfoundland. Legend had it that the Isle of Demons was filled with demons and beasts that attacked anyone that dared step foot on its shores.

Why Roberval marooned his cousin remains unknown. Some say he hated the relationship between her and her lover, while others say he wanted to take over her properties. One account also states that Roberval actually marooned Rocque’s lover, and Rocque opted to join him, although another version states that it was Rocque who was marooned, and her lover decided to join her. There is no account of the maid willingly joining.

The maid and Rocque’s lover died on the island, but Rocque survived and even birthed a baby. The baby later died, leaving her alone on the island until she was rescued by some fishermen in 1544. The veracity of this story remains in doubt, since the Isle of Demons was removed from maps in the mid-17th century because it was determined not to exist.[10]

1 Saxemberg Island

Saxemberg Island was discovered by John Lindesz Lindeman in 1670. According to Lindeman, the island, which is supposedly located in the Southern Atlantic, is flat with a mountain in its center. Several follow-up expeditions claimed to have spotted the island, even though Australian navigator Mathew Flinders carefully searched for it in 1801 and found nothing.

In 1804, Captain Galloway claimed to have spotted the island and even its central mountain. Captain Head corroborated his claims in 1816. Other sailors also said they saw the island, and some even claimed to have landed on it.

One Major General Alexander Beatson even made a detailed report of the flora of the island in 1816. He furthered his theory by claiming that Saxemberg Island, along with the islands of Ascension, Tristan da Cunha, and Gough (which all exist) were formed from the same continent. Saxemberg Island itself continued appearing on maps until it was agreed to be nonexistent in the 19th century.[11]

Read about more lying maps on 10 Map Mistakes With Momentous Consequences and 10 Monumental Map Blunders And Lies.