Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Clever Hoaxes That Fooled Experts

For as long as people have been making discoveries and expanding the breadth of human knowledge, others have been lying about it. Maybe the hoaxer seeks fame and fortune, maybe he just can’t admit he’s wrong, or maybe he just likes a good prank. Whatever the motivation, hoaxes have led people astray throughout history.

Fortunately, most hoaxes aren’t crafty enough to trick experts. Scientists, scholars, and historians can usually spot fakes, forgeries, and jokes rather quickly. However, some hoaxes were so skillfully executed that they managed to trick experts and most of the world for decades.

10 Japanese Paleolithic Discoveries

Amateur Japanese archaeologist Shinichi Fujimura had an uncanny knack for finding buried relics. He was rumored to have supernatural powers and was given the nickname “God’s Hands.” For 20 years, his discoveries illuminated Japanese prehistory.

The self-taught archaeologist had investigated more than 150 archaeological sites in Japan. Fujimura discovered evidence of shelters, delicate stone tools, and a cache of colored stones that were 700,000 years old. His finds suggested a branch of primitive man in Japan that was far more advanced than any previously discovered. Fujimura’s discoveries were rewriting the story of human evolution.[1]

Any criticism of Fujimura’s finds was silenced and ignored. A reporter heard rumors of doubt about Fujimura, and he secretly videotaped him burying tools at a site and pounding the earth down with his foot. When Fujimura was confronted, he confessed to faking two finds. As experts reviewed his major discoveries, Fujimura admitted to faking everything in 2000.

9 The Venus Of The Turnip Patch

In 1937, a French farmer was working in his field when his plow nearly broke on a hard rock. The farmer dug into the ground, and he uncovered a beautifully carved marble statue. He reported his discovery, and crowds flocked to his farm.

France’s minister of fine arts heard about the farmer’s find, and he appointed a commission to study it. They determined that the statue was an authentic representation of the neo-Attican period—Roman sculpture made between 200 BC and AD 200. The statue was declared an antique work, and the French government proclaimed it a national treasure.[2]

Two years later, a local artist, Francesco Cremonese, claimed he had sculpted and buried the statue. Cremonese considered his art equal—if not superior—to the art displayed in museums, and he was annoyed that his work wasn’t getting more attention.

Nearly everyone doubted Cremonese’s claim. He invited the disbelievers to his workshop, where he showed them pieces he had smashed off of the statue before he had buried it. Experts compared the pieces to the damaged parts of the statue. They were a perfect match.

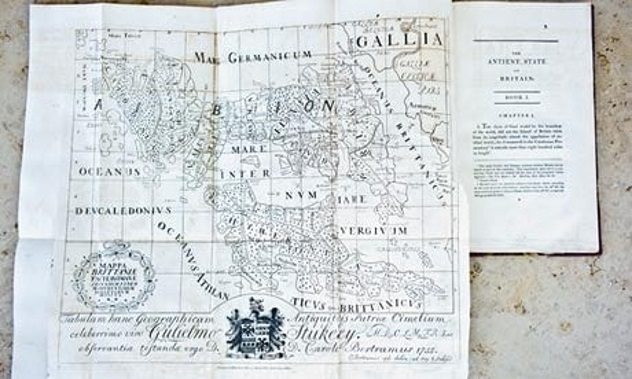

8 The Description Of Britain

In 1747, English teacher Charles Bertram wrote to the famous English antiquarian William Stukeley and described “a curious manuscript history of Roman Britain by Richard of Westminster,” which he had seen at a friend’s house.[3]

Stukeley requested a copy, and the document impressed him. The author of manuscript had access to several lost, original sources, and he posessed enough geographical knowledge to create a comprehensive map of the British Isles under the Roman Empire. Bertram published the documents, and antiquarians and historians were delighted with the book, The Description of Britain, which showed new information about Roman Britain, including a whole new province, many new place names, and new details about the early Christian martyrs in England.

The text was treated as a legitimate and major source of information on Roman Britain for the next 100 years. In the mid-19th century, scholars noted that the document had been written in poor Latin and that it had referenced a modern book. The author of the manuscript is believed to be Bertram, although no one knows why he faked the text.

7 Calaveras Skull

On February 25, 1866, a miner discovered a human skull buried 40 meters (130 ft) beneath the ground. It had been covered with million-year-old volcanic deposits, which meant the skull belonged to the oldest known human being discovered in North America.[4]

The state geologist of California, Josiah Whitney, declared the discovery legitimate. Whitney claimed the skull was between five and 25 million years old and that it proved that humans, mastodons, and elephants had coexisted in North America.

Some scientists doubted the skull’s age. The Calaveras Skull was a fully developed modern skull, and it bore no evidence of human evolution. If the skull was genuine, it would disprove the evolutionary theory of human origins.

A miner soon confessed that he had stolen a skull from a Native American burial site and had hidden it as a practical joke. However, some people still believed that the skull was ancient. In 1907, a scientist tested the skull and proved that it was only 1,000 years old.

6 Walam Olum

In 1836, Constantine Rafinesque published the Walam Olum or Red Record, a history of the Lenape Native American tribe. The book began with their creation myth, and it told how the Lenape entered the New World, overcame a Midwestern mound-building people, and continued eastward. The story ended with the first white men arriving in ships.

Rafinesque claimed that his source was a bundle of wooden plaques that had been engraved and painted with Lenape symbols. He said he had been given the plaques from a doctor, who had received them as a payment from a Lenape patient. Unfortunately, Rafinesque misplaced the plaques after he had translated them; there was no proof of their existence.

The book was treated as an accurate account by historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists for many years. In the 20th century, people began doubting the book’s authenticity. A scholar, David Oestricher, decided to study the document. He interviewed elderly Lenape, who told him that they had only heard of the book recently from anthropologists and archaeologists.

Oestricher then reviewed the manuscript itself. He found that Rafinesque had repeatedly crossed out Lenape words, replacing them with ones that better matched his English “translation,” which proved that Rafinesque had written the Walam Olum in English before he had translated it to Lenape.[5]

5 Modigliani Sculptures

In 1909, Amedo Modigliani left his hometown of Livorno after he received negative reviews from critics. According to legend, before he left, Modigliani threw several sculptures into a canal after his friends laughed at his work.

In 1984, an exhibition of Modigliani’s work was organized to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth. The event’s organizer and the town’s city council decided to finance a search for the famous missing sculptures.

After eight days of excavations, a carved bust was discovered in the bottom of the canal. A few hours later, two more were dug up. All three statues were in Modigliani’s style. Several historians and art history experts believed that the sculptures were authentic. Only one art historian stated that the sculptures were so immature that even if they were authentic, Modigliani had been right to throw them away.[6]

Three students later came forward and confessed to making one of the heads as a prank. A local artist confessed to creating the other two; he had wanted to mock art critics.

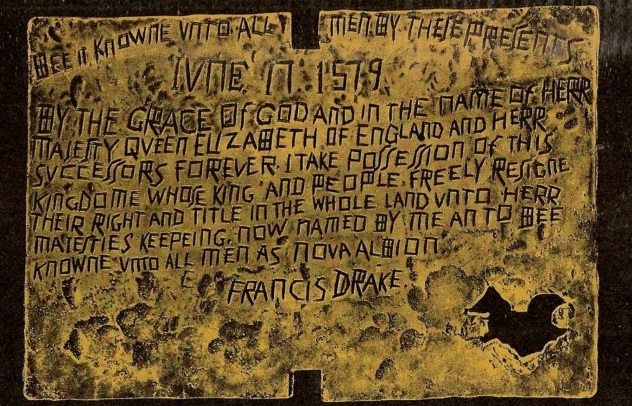

4 Drake’s Plate Of Brass

According to legend, Francis Drake posted a brass plaque after landing in California in 1579. In the early 1930s, Herbert Bolton, a distinguished professor of California history, was eager to find it. He encouraged his students to search for the plate, but no one had discovered it.

Four of Bolton’s friends and fellow historians decided to play a joke on him. They created a design based on a detailed account of Drake’s voyage, and they chiseled the lettering into a brass plaque. They hid the plate near the supposed location of Drake’s landing.

A man discovered the plate, stored it in his car, and later threw it away on the side of the road. The plate was found again three years later, and the finder brought it to Bolton. Bolton believed that the piece was authentic “beyond all reasonable doubt,” and he presented it to the California Historical Society.[7] Members of the society were delighted with the find, and they donated $3,500 to buy the plate for the university’s library.

The plate became a cherished museum piece. It was exhibited at the Smithsonian and around the world, reproductions were given to Lady Bird Johnson and Queen Elizabeth II, and it was mentioned in textbooks.

The hoax was successful for over 40 years. In 1977, scientists determined that it was a modern creation after it had failed physical and chemical tests.

3 Etruscan Terra-Cotta Warriors

John Marshall was an English archaeologist who purchased artifacts for New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he bought three terra-cotta warriors for the museum between 1915 to 1921. He praised his purchase, claiming, “I can find nothing approaching it in importance.”

The statues were thought to have been created by the Etruscans in the fifth century BC. The museum hired America’s leading ceramic expert to confirm the sculptures’ authenticity. Neither he nor the museum’s own curators of classical art detected any problems with the pieces. The museum accepted the works as genuine.

The terra-cotta statues were put on display in 1933, and they were hailed as spectacular examples of Etruscan art.[8] A few scholars raised questions about the authenticity of the statues, and an Italian art dealer mentioned rumors that the statues were forgeries. The museum ignored the concerns and rumors.

In 1960, the museum could no longer ignore the suspicions. Chemical tests were performed on the statues, and they contained manganese, an element that the Etruscans had never used. Further tests showed that the statues had been broken before they were fired to produce fragments.

The statues were proved fake the next year when Alfredo Fioravanti confessed that he had helped make the sculptures. He had kept the left thumb of one as a souvenir.

2 The Charlton Brimstone Butterfly

In 1702, butterfly collector William Charlton sent a specimen to James Petiver, who was a respected entomologist. Petiver was delighted with the butterfly, as he had never seen one like it before. He wrote that it “exactly resembles our English Brimstone Butterfly . . . were it not for those black spots, and apparent blue Moons on the lower Wings.”

In 1763, naturalist Carl Linnaeus examined the butterfly and declared it to be a new species. He named it Papilio ecclipsis, and he included it in the 12th edition of his Centuria Insectorum.

30 years later, entomologist John Christian Fabricius examined the butterfly and realized it was a fake. The black spots had been painted on the wings; the rare butterfly was nothing more than a common Brimstone.

When the curator of national curiosities at the British Museum, where the butterfly was stored, heard it was fake, he “indignantly stamped the specimen to pieces.”[9]

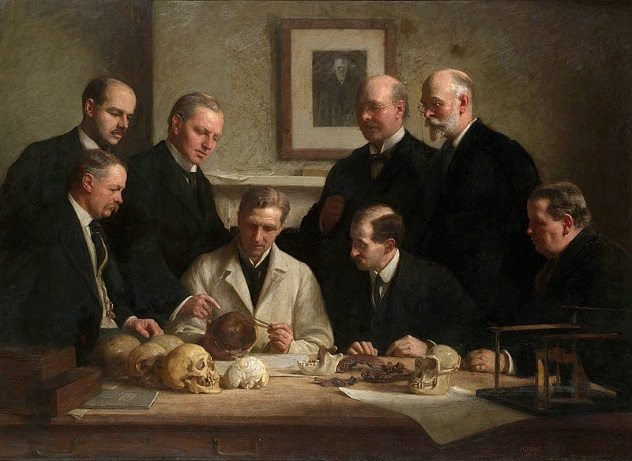

1 Piltdown Man

In 1912, Charles Dawson, an amateur fossil hunter, wrote a letter to Arthur Smith Woodward, keeper of geology at the British Museum. Dawson told him that he had uncovered a portion of a human skull that would “rival” the German fossil jaw belonging Homo heidelbergensis, the first early human species to live in colder climates.

Dawson and Woodward excavated the area where the skull had been found. They discovered several pieces of a humanlike skull, an apelike mandible, some worn molar teeth, stone tools, and fossilized animals. The men estimated that the individual lived around 500,000 years ago.

Dawson and Woodward presented their findings to the Geological Society of London. They claimed that they had discovered the “missing link” between ape and man, and they named their discovery Eoanthropus dawsoni (Dawson’s dawn man).

The UK’s evolution research community enthusiastically embraced the discovery, as it established the UK as an important site in human evolution.[10] The Piltdown Man was hailed as a major missing link in the ancestry of man.

In the next few decades, more and more hominin fossils were discovered, and the Piltdown Man lost its significance as a singular missing link. In 1953, scientists used a new technique of fluorine dating, which proved that the Piltdown Man’s bones were not all the same age and that none of them were more than 720 years old. Additional research showed that the bones were a mixture of carefully carved and stained human and ape bones.

In 2016, researchers reviewed the Piltdown Man again. They believe that a single person created the hoax, most likely Charles Dawson. Dawson had a habit of small-time forgery, and he was desperate for acceptance and recognition within the UK scientific community. He dreamed of being elected a fellow of the Royal Society, but he was never nominated—until he announced the Piltdown discovery.

For more egregious hoaxes, check out Top 10 Holy Hoaxes and 10 Bizarre Hoaxes Involving Nonexistent People.