Travel

Travel  Travel

Travel  Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

10 Weirdest Life Cycles In Nature

Being born is among the hardest things any creature will ever do. Going from a single cell to a fully formed organism ready to face the world is a path we all take. However, no two species face the exact same struggle to be born, and there are quite a variety of odd life cycles in nature.

It is no surprise, then, that some of the pregnancies contrived by evolution can seem extraordinarily weird, if not fodder for horror movies. Here are ten of the strangest ways animals enter the world.

10 Incest Cannibal Babies

Adactylidium mites have such a rapid life cycle that they emerge from their mother already pregnant. These mites survive by eating the egg of a thrips—a winged insect that is less than 1 milimeter long. A single egg supplies all the energy and nutrients the mite will require for her entire life. It also provides the energy needed for the mite to raise her brood.

The mite’s life cycle begins inside its mother. The eggs hatch within, producing a brood of six to nine females and a single male.[1] The larvae proceed to devour their mother’s tissue. The larvae then develop into adults while still inside the exoskeleton of the mother. While there, the male mates with his sisters, impregnating them. Now carrying fertilized eggs, the mites burst out of their mother and look for a thrips egg of their own to eat. The male mite, his job done, makes no effort to feed himself and simply dies. The female mites wait for their own children to eat them.

9 Mammals From Eggs

Children learn in school is that one of the defining characteristics of mammals is that they give birth to live young. No one, it seems, told the monotremes. This group of mammals is identified by the fact that they all lay eggs. Today, only five species of monotremes exist—the duck-billed platypus and four species of echidna.

Monotreme eggs tend to be small and have a leathery, rather than hard, shell. The monotreme incubates the eggs for several days until the young hatch. Then, in the case of echidnas, the baby, or puggle, crawls into its mother’s pouch.[2] Compared to other mammals, the newly hatched baby is tiny and practically helpless. For several months inside the pouch, the puggle laps up milk that is produced from mammary glands in the skin. Eventually, the puggle is developed enough for the mother to place it in a burrow, where she will return to feed it every several days until it’s mature enough to survive on its own.

8 Mouthbrooders

Fish are not always known for their parenting prowess. Often, eggs are released, fertilized, and the young left to fend for themselves. It is true that some species will defend their eggs and young, but for some fish, it is just too risky to leave them alone at all. These fish, known as mouthbrooders, carry their eggs in their mouths until they hatch and will often keep their young there well afterward.

In some species, like the pearly jawfish, it is the father who will have a mouthful of eggs. For the duration of their development, he will hold onto them, unable to feed himself until they hatch. African cichlids are maternal mouthbrooders. The mothers go up to 36 days without feeding. Once the eggs hatch, she will allow the young out to feed themselves, but she can signal them to swim back in for protection if she senses danger.[3]

Unfortunately, not even this tactic can always protect their young. The cuckoo catfish attacks cichlids to get them to spit out their eggs. While the mother cichlid is gathering them back up, the catfish deposits her own eggs among them. The catfish eggs hatch more quickly than the cichlid’s and proceed to feast on the cichlid eggs inside the safety of the mother’s mouth.

7 Gastric Brooding

Sometimes, the mouth simply isn’t safe enough for a child to live in. For the gastric brooding frogs, eggs would be kept safe in the stomach. The mother would lay her eggs in the usual fashion but then eat them. Up to 40 eggs would be eaten, though no more than 20 young were ever seen to develop within a mother’s stomach. It is possible that the stomach acid digested some of the eggs. To avoid being dissolved, the eggs, and the tadpoles that hatched from them, produced a mucus which stopped production of the acid—leaving the mother unable to eat while carrying her young.

As the young grew, the stomach expanded with them until it took up the majority of the frog’s body space. The mother’s lungs collapsed to make room, and she had to breath through her skin. Only after six weeks would the mother release her fully formed young.

Unfortunately, the two species of gastric brooding frogs went extinct in the 1980s.[4] But in 2013, scientists took the first steps in returning the frogs to life. Using cloning techniques, they were able to create living embryos. It is hoped that the gastric brooding frog will soon be swallowing her young again.

6 Three Vaginas

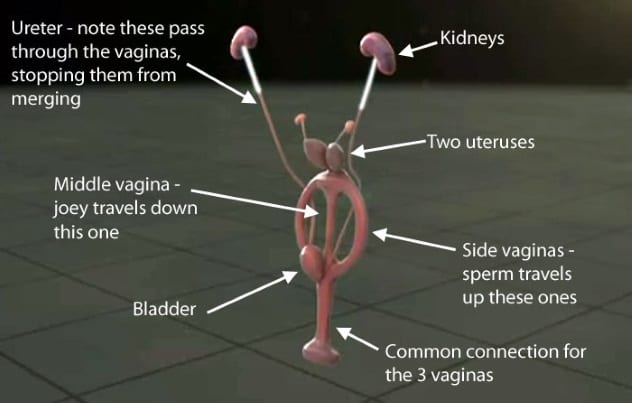

Kangaroos, as well as several other marsupials, have a female reproductive system that can seem a little confusing at first but is actually the key to reproducing quickly. In place of the standard single vagina, kangaroos have three. The two on the sides are used to pass sperm to the uteri (of which there are two), while the middle is the one that joeys pass through to enter the world.[5] They have other developments which may allow them to remain almost permanently pregnant.

The kangaroo egg cell is fertilized by sperm and allowed to develop for just 33 days before the young joey emerges. Blind, pink, and shriveled, the joey must crawl up through the fur of its mother and make its way to the pouch and find a teat to feed from. For the next 190 days, it stays in the pouch feeding until it will begin to leave the pouch, returning to suckle. The mother kangaroo can then begin to develop another embryo that will crawl out and into the pouch. The mother will produce two different types of milk—one for the newborn and one for the older joey.

That’s not the end of it, though. The mother may get pregnant again at this point, even though she has no more room to feed a young one. Instead, any embryos created while a newborn is still suckling will be held in a form of arrested development in one of the uteri and only begin to grow again when there is a spare teat.

5 Birth Through A Pseudo-Penis

Female spotted hyenas can be hard to spot in the wild. This is not because they are particularly shy, far from it, but because they display what looks awfully like an 18-centimeter (7 in) penis. In fact, this appendage is a pseudo-penis formed from an elongated clitoris. The female pseudo-penis does pretty much everything a penis does, even getting erections, but it does not deliver sperm.[6] To have sex, a female hyena must retract her pseudo-penis, and the male must deliver his sperm through a channel that runs directly through it.

As this is also the birth canal, childbirth in female hyenas can be very traumatic and is definitely not a laughing matter. A 1.8-kilogram (4 lb) cub must be passed through a hole barely 2.5 centimeters (1 in) across. For a first-time hyena mother, there is an almost 60-percent chance that the cub will become stuck in the pseudo-penis and die. If the cub is not eventually released, this can prove fatal to the mother, too. When the first cub is born, it tears the pseudo-penis, and a stretchy patch of scar tissue forms that makes subsequent births easier.

Why does the female spotted hyena suffer so much to have a pseudo-penis? As of yet, no researchers have come up with a compelling explanation.

4 Male Birth

In most species where eggs are cared for within the body, it is the mother who takes responsibility for nurturing them. For seahorses, pipefish, and leafy sea dragons, it is left to the fathers to get their offspring from eggs to hatchlings. All these fish perform lengthy mating rituals which involve the male and female wriggling and dancing for hours together. It is thought that their motions allow them to synchronize movements, enabling the female to accurately deposit her eggs into a pouch on the male before swimming away.[7]

In male seahorses, the eggs are then fertilized and surrounded by fleshy tissue that regulates oxygen and nutrition for the eggs. The male can swell to a much greater than normal size, as up to 2,500 eggs develop within him. When the young are all hatched, the male with use muscle contractions to spill the tiny hatchlings out into the ocean. At this point, he is ready for his next batch of young and takes no interest in the babies he has just carried.

3 Under The Skin

The Suriname toad (Pipa pipa) is an unusually protective mother. Used to hiding from predators at the bottom of bodies of water, it will not allow its offspring to simply swim about until they are completely ready to survive on their own. When a male Suriname toad is ready to breed, it will signal its readiness by making a clicking sound with a bone in its throat. Once a female emerges, the male will cling to her back for up to 12 hours as they swim in flipping circles through the water.[8] This allows the male to fertilize the eggs and hold them against the mother’s back.

Why is it important that the eggs remain against the mother’s back? Because it is where they will stay until they are fully developed. The mother will grow skin over the eggs and trap them within her flesh. As the young grow, they can be seen moving and quivering under the flesh. The Suriname toad will not even allow its babies to emerge as tadpoles. When the young have developed into toadlets, they will punch their way out of their mother and swim off as fully independent beings, leaving her with massive holes in her back.

2 Eating Siblings

The least you can hope for from life is that the struggle for survival will wait until after your birth. In nature, though, you can never rest easy, not even within your mother. A sand tiger shark may start with as many as 12 fertilized eggs inside her, but usually, only two will emerge. Once the eggs hatch, the largest baby sharks will kill and eat their brothers and sisters. This is called intrauterine cannibalism.[9] This act of cannibalism allows the two survivors, held in the right and left uteri, to develop into roughly one-meter-long (3.3 ft) newborns able to survive on their own. The mother also provides unfertilized eggs for the baby sharks to eat during their nine-month gestation.

This method of motherhood gives the sand tiger shark the best chance of having strong offspring. The mother will mate with a number of males, but by allowing her children to eat each other in utero, only those with the best genes will survive.

1 Darwin’s Monsters

There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae . . .

While many see in nature the glory of an all-loving God, Charles Darwin thought it impossible that such a being could have knowingly made parasitic wasps. Only evolution is capable of making such wickedly efficient killers.

Parasitic wasps are incredibly common and target a huge number of other invertebrates.[10] From spiders to butterflies to other parasitic wasps, they will hunt them down and lay their eggs within the still-living bodies of their prey. Some will paralyze their prey with venom, leaving them unable to move as the wasp’s larvae devour it. Others will attack caterpillars so that their own eggs can benefit from the caterpillar’s continued feeding. The larvae will often release chemicals that control the mind of their host to give them the best chance of survival, such as making a host spider spin them a cocoon. Whatever the host, the endpoint is the same—something you do not want to look too closely at is coming bursting out of you.

Read about more bizarre animal births on 10 Animals Able To Reproduce Via ‘Immaculate Conception’ and 10 Bizarre Birth Mutations In Animals.