Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Strange Mourning Items From The Victorian Era

From 1837 to 1901, Queen Victoria ruled over England. When her husband, Prince Albert, died, she began wearing black, declared that she was in mourning . . . and never stopped. She never remarried and raised all of their children alone. To the English people, this was incredibly tragic and romantic at the same time, so they began to admire it.

Death suddenly became cool, and mourning a loved one became much more dramatic. This obsession with death became ingrained in the culture of the time. Objects are a part of culture in all shapes and forms, so it isn’t surprising, then, that people of the Victorian era collected items revolving around mourning and death.

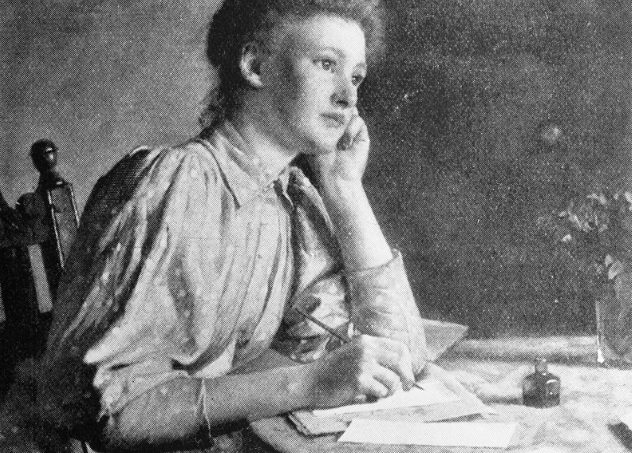

10 Extravagant Wills

Most young people don’t obsess over the thought of their own death, but of course, in the Victorian era, mourning was in fashion. People wrote down what they would like to happen in case of their death, even when they were perfectly healthy. Knowing that the letters and wills would be kept by their families forever, they would flourish them as if they were writing poetry.

A woman named Mary Drew practically wrote an entire book of instructions for what to do after her death. She’d had a miscarriage and was dying in the hospital. Her last will and testament was 56 pages long. During the Victorian era, receiving mementos that once belonged to the dead was extremely important. The vast majority of the items Mary gave away were pieces of jewelry to female friends and books for the men. For the friends who were left without getting anything valuable, Mary made sure locks of her hair would be cut and given to them.[1]

9 Hair Jewelry

Queen Victoria kept her late husband Prince Albert’s hair inside a locket that she wore every single day. It became very common for people to keep locks of hair that once belonged to their loved ones. Many women decided that they wanted to carry a piece of a deceased loved one around with them all the time, just like Queen Victoria. So, what better way to do that than by turning their hair into jewelry?

As the years went on, people became more creative with their hair jewelry. They began to braid and weave the hair into intricate designs on brooches, earrings, and necklaces. Sometimes, they even made wreaths of the various locks of hair collected from multiple dead loves ones. Since hair is very resistant to decay, it was a good thing to keep around that was never going to rot. These hair jewelry pieces are still remarkably well-preserved today in museums.[2]

8 Mourning Rings

While hair jewelry could be made even if the death of a loved one was sudden and unexpected, it wasn’t enough for some people. If someone knew they were going to die within a few months, they sometimes commissioned special jewelry for the occasion.

One woman in particular, Ada Lovelace, was diagnosed with cancer in 1852. At the time, this was an absolute death sentence. So, she wrote instructions for special rings to be made for her husband and oldest daughter. On her husband’s ring, she wrote that she would hope their souls would be eternally bound. Even though she didn’t get along very well with her daughter, she said she honored her “sincerity.” For her two youngest sons, she left some money, asking them to buy rings for themselves in her honor.

Mrs. Lovelace was not the only person to give mourning rings, either. Documents and diaries from the Victorian era tell stories of specialized rings that people wore on a daily basis.[3]

7 Mourning Dress

Whenever someone died, the family was socially obligated to wear all black every day during a designated mourning period. The clothes were called “mourning dress” and were a symbol to the rest of the world that the wearers were sad and needed to be left alone. People whose loved ones recently died were expected to not show up to parties or other social engagements. If anyone whose loved ones recently died showed up in public in clothing that looked too colorful and cheerful, it was a sign of disrespect. However, it put a lot of stress on the wives of families to make sure everyone had black clothes that would fit, especially if they had growing children.

In 1875, a pamphlet calling out the custom was finally published by a writer named Keith Norman MacDonald, saying that it was silly and actually embarrassing. Despite the fact that many people were self-aware, the mourning dress tradition continued for a few more decades.[4]

6 Mourning Lingerie

During the Victorian era, mourning dress wasn’t just what people wore on the outside. Women wore black all the way down to their lingerie. At the time, death wasn’t just cool; it was sexy. Women were encouraged to take arsenic and opium in order to look very pale and near-death, because women dying of tuberculosis were considered to be very beautiful. Combine that deathly-white skin with black lingerie, and it was enough to drive some men wild.

During the Victorian era, people were very repressed on the outside and secretly very kinky in private. White lingerie was seen as being innocent, usually reserved for a woman’s first sexual encounter on her wedding night. After the Victorian era, people became more open about their sexuality, and images of pinup girls and bombshell blondes in movies always wore black lingerie, because it was seen as far more erotic and sexually aggressive than any other color.[5]

5 Postmortem Photographs

Since photography was newly accessible to even middle-class people during the Victorian era, people felt the need to remember what their loved ones looked like before they were put in their graves. At the time, anyone who was alive needed to stay perfectly still for a very long time, which is why pretty much everyone in old pictures was frowning or had a relaxed facial expression. Photographing someone who was dead was much easier, considering that they weren’t going to move and blur the picture.[6]

Another trend at the time was “spirit photography.” The images of another person or the same subject’s face would be floating in front of the subject. Even Queen Victoria’s son, Arthur, had a spirit photograph. During the long exposure, his nanny leaned into the frame, trying to fuss with his clothing, and ended up semi-transparent in the picture.

People who were dabbling in the occult believed that ghosts had found a way to show themselves through photographs. The National Science and Media Museum has a gallery of their spirit photography collection from the Victorian era. By the late 1800s, people understood that it wasn’t really a ghost, but they would still have some fun by creating their own silly ghost photos.

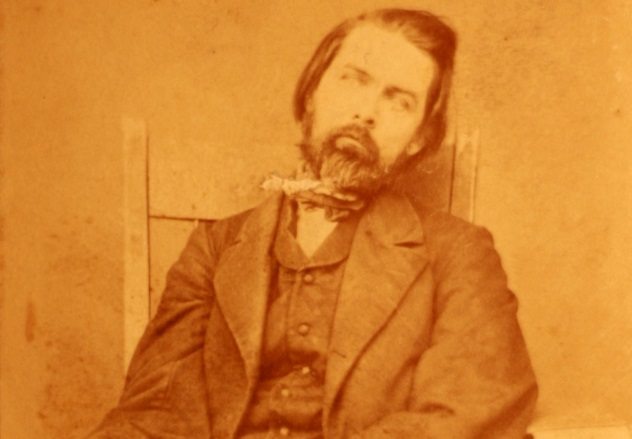

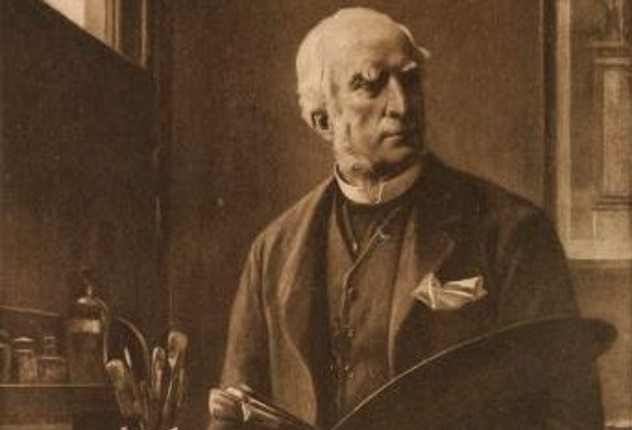

4 Sketches

Not every family could afford a photograph of their dead loved one, and some still preferred drawn or painted portraits.

An artist named John Callcott Horsley would do volunteer work by visiting a morgue to sketch images of recently deceased children. Many families were too poor to pay for photos or professional portraits. If he heard a child had died in town, Horsley would go there quickly, while the facial muscles were still relaxed and it looked more like the child was peacefully sleeping, rather than dead. He wrote in his diary, “I had a duty to do it. Indeed had I not done it, it would not have been done.” When John’s own father died, the first thing he did was pull out a sketchbook.

Other artists would make sketches of family members while they were still alive, if they caught tuberculosis or any other illness that was basically a death sentence.[7]

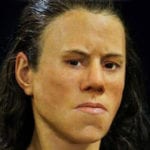

3 Effigies And Death Masks

When Queen Victoria’s husband died, she had an effigy made of black marble in his likeness that was placed in the Frogmore Mausoleum. She was very happy with the likeness of her love, saying that it reflected his “sweetness and calmness.” When Queen Victoria eventually died, she joined her dear Prince Albert in her tomb. The top of the grave was decorated with an effigy etched out of white alabaster.

Obviously, something like this was time-consuming and very expensive. The queen was not the first to do this, either. During her lifetime, wealthy families would pay for alabaster effigies of their loved ones.[8] Photographs were taken of dead relatives almost immediately after their death and then used to make statues for the family tombs. Sometimes, there were even casts taken of the head of the dead person so they could make an even more accurate death mask.

2 Funeral Dolls

Normally, at a wake, an open casket allows mourners to see their dead loved one for the last time. However, many people felt that it was just too much to bear seeing a dead baby. So, they created wax dolls to look like their children, even using the real hair from their head. In certain circumstances, if a child was stillborn, miscarried, or lost somewhere outside of the home, a wax effigy could be buried in the place of the actual body.[9]

Death was so much more common during the Victorian era that children were exposed to it far more often than they are today. In the late 1800s, the University of Wisconsin published a book called A Study of Dolls, and they revealed that out of the test group of children, a large number had given their dolls a pretend funeral and even went as far as to bury the doll in the backyard. An smaller number of children would dig the doll up, just to check if the dead really do go to Heaven.

1 Stationery And Memoriam Cards

In the Victorian era, if someone received their mail and saw a white envelope with a black border, they knew someone was dead. In the works of Charlotte Bronte and Charles Dickens, this special mourning stationery makes an appearance every time a character learns of anyone’s death. The idea was that the black lines would prepare the reader to know that bad news was inside, and it gave them a chance to open it in private.[10]

Inside these envelopes, there weren’t always just letters. Sometimes, the families paid for elaborate “memoriam cards” that had images in filigree or even looked like doilies. When a child died, the memoriam cards were done on white paper to symbolize the loss of an innocent life, and the death of an adult was done on black paper.

As the years went on, people began to see buying special mourning stationery as a frivolous expense, especially when everyone already had regular stationery around the house that could be used, instead.

Shannon Quinn (shannquinn.com) is a writer and entrepreneur.

For more Victorian weirdness, check out 10 Bizarre Entertainments Of Victorian London and 10 Strange Christmas Traditions From The Victorian Era.