History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

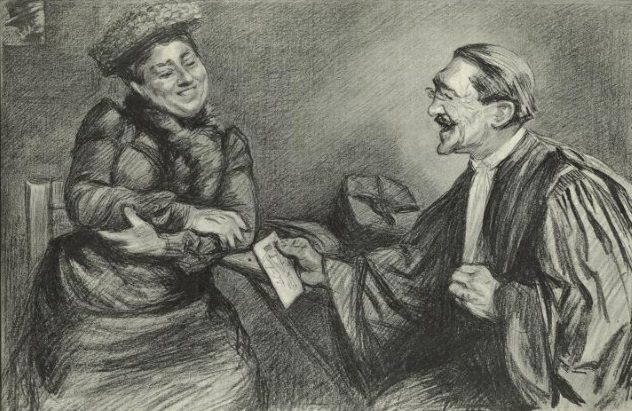

10 Heinous Crimes From The Beautiful Era

La Belle Epoque was a period of peace and prosperity for France between the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and World War I. It was characterized by flourishing arts and literature, numerous scientific and technological advances, and a pervasive optimism and joie de vivre. The term itself was coined later, when people growing up under the shadow of the Great War looked back fondly at how good things used to be.

They might have been looking through rose-tinted glasses, though. The era had problems. Most of the prosperity and decadence were only experienced by Parisian bourgeoisie, while the working class and the poor had it rough, as always. The period wasn’t free from scandal, either, as evidenced by the Dreyfus Affair. And, as we are about to see, La Belle Epoque saw its fair share of gruesome crimes, as well.

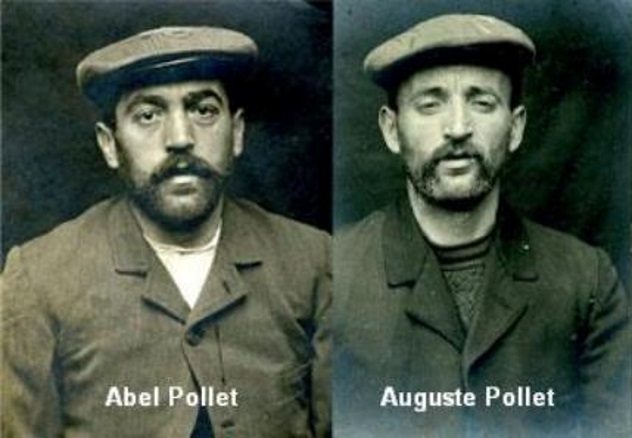

10 The Pollet Gang

At the beginning of the 20th century, France had a moratorium on the death penalty at the behest of its new president, Armand Fallieres, who was a staunch opponent to capital punishment. However, the actions of one violent gang were so heinous that the public demanded blood.

The band in question was called the Hazebrouck gang, also known as the Pollet gang after its leaders, brothers Abel and Auguste. At the time of their trial, it was reported that the group contained 27 members and stood accused of 118 crimes, including assault, robbery, and murder.[1] Abel Pollet confessed with a modicum of glee and boastfulness to the triple murder of an elderly couple and their 55-year-old daughter in the northern village of Violaines. Eventually, this earned him and three accomplices the death penalty, and this time, President Fallieres didn’t commute it to a life sentence like he did for many other criminals.

On January 11, 1909, the sentence was carried out in Bethune by notorious executioner Anatole Deibler. A bloodthirsty crowd of 30,000 came to witness the event and had to be restrained by the military from tearing the corpses to pieces. Abel Pollet’s last words were, “Down with the priests! Long live the Republic!”

9 Prado The Ladykiller

He was known as Louis Prado and as Count Linska de Castillon, a French nobleman and the supposed son of a South American president. Neither one was likely his real name. He was articulate and superficially charming and, as such, developed a reputation as a ladies’ man. In the end, though, he became remembered for what he truly was—a thief and a murderer.

Although mostly forgotten today, Prado’s trial was a bit of a cause celebre in its day that attracted a lot of attention. At first, he seemed content simply to seduce women, marry them, and live off their wealth. He supplemented his income with a secondary career as a robber. However, on January 15, 1886, Prado attacked a woman named Marie Agaetan in her apartment in Paris. He cut her throat with a razor so deep that her head was almost severed from her body. Mrs. Agaetan was known as la femme aux diamants due to all the jewelry she wore, and her husband was a croupier who never came home before 2:00 AM. Therefore, she made a perfect target for Prado.

He almost got away with it. Two years later, Prado was arrested for shooting a police officer during a failed robbery. Following an investigation, his two mistresses were also arrested for possession of stolen jewelry. One of them, Eugenie Forestier, testified against him. She claimed that on the night of the murder, Prado visited her and asked her to get rid of his bloodstained clothes and razor.[2] Prado was found guilty and executed on December 28, 1888.

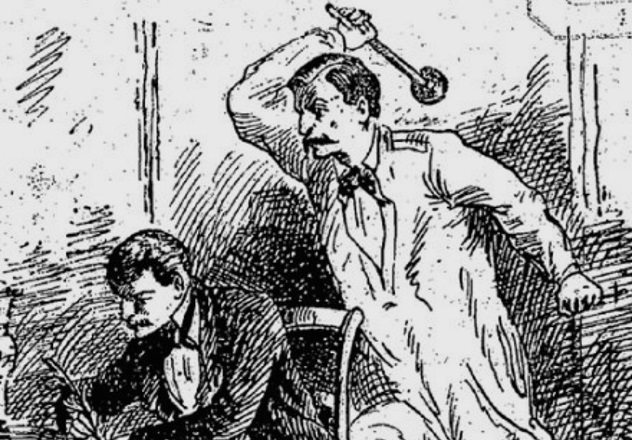

8 Prevost The Policeman

Prevost was an officer of the law, meant to protect the people of Paris. However, when presented with the opportunity for financial gain, he showed a gruesome appetite for murder. It started when Prevost arranged a meeting with a jeweler named Lenoble under the pretense of making an acquisition. While his victim was unaware, the policeman came up from behind and bludgeoned him with an iron rod-and-ball. Afterward, Prevost proceeded to spend several hours skinning, dismembering, and dicing Lenoble’s body in order to dispose of it in bits throughout the sewers of Paris.

Despite Prevost’s ghastly efforts, the jeweler’s remains were found, identified, and traced back to the policeman. After confessing to the crime, Prevost made the shocking revelation that he had done the same thing before. A few years prior, the man of the law killed his lover, a woman named Adele Blondin, and disposed of her body in the same manner.[3] He was condemned and executed in 1880.

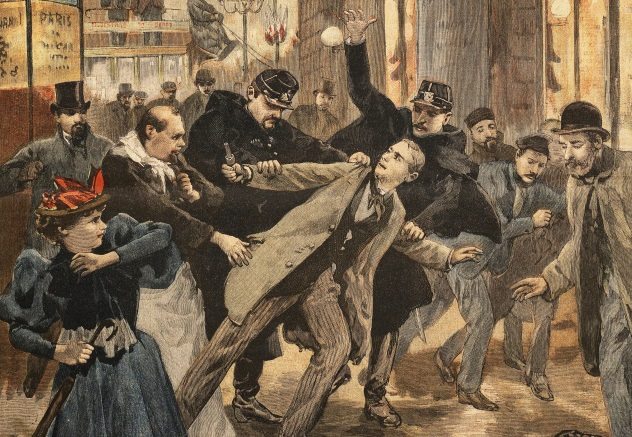

7 The Bombing Of Cafe Terminus

Despite being considered an era of peace, La Belle Epoque was not free from terrorism. In fact, some argued that the February 12, 1894, bombing of a popular Parisian cafe started the terrorism blight of the modern age. The perpetrator was Emile Henry, a 21-year-old intellectual whose father was a Communard and whose older brother was already an outspoken proponent of anarchism.

Bombings and assassinations had happened before. In fact, Henry himself said he committed the attack as revenge for the execution of Auguste Vaillant, another anarchist who threw a bomb into the Chamber of Deputies to protest their treatment of the poor. However, Henry targeted ordinary persons as opposed to politicians, military, or policemen. His goal was to kill as many people as possible because there was no such thing as “innocent bourgeois.”

That day, Henry walked down the Avenue de l’Opera and stopped at multiple cafes. He left them alone because he didn’t feel they had enough targets. Finally, he stopped at Cafe Terminus, where he ordered two beers and a cigar before lighting the fuse on the bomb and throwing it in the middle of the room.[4] One person died from the explosion, and 20 were seriously injured. Henry was captured and used his trial to deliver his anarchistic manifesto. He went to the guillotine a month after the bombing.

6 The Lies Of Therese Humbert

The crimes of Therese Humbert are certainly nowhere near as grave as the others included in this list, but they warrant mention for pure interest and originality. She was born into a poor family in Toulouse and yet went on to become one of Paris’s premiere A-listers during La Belle Epoque. How? As one of her contemporaries put it, “She lied like a bird sings.”

Therese’s technique, by and large, was to convince people that she always had money coming in from one source or another, typically an inheritance. First, she used this trick to marry Frederic Humbert, the son of a local politician, who would later take part in his wife’s schemes.

Therese’s most successful con was the story of Robert Henry Crawford, an American millionaire who allegedly left her a giant inheritance after she saved his life during a train ride. In the early 1880s, she managed to parlay this tale into a considerable money loan, which Therese used to move into a swanky Parisian neighborhood. For almost two decades, the Humberts lived in luxury by building a noble reputation, making it easier to secure new loans to pay off the older ones. All the while, Therese assured her creditors that she would pay them back after settling an inheritance dispute with Crawford’s two nephews. At one point, they were even summoned to court in Paris, and Therese brought her own brothers to play the Crawford nephews.[5]

The con was finally discovered once the loans outweighed any potential inheritance. Her trial in 1901 was highly publicized, but the media was more interested in embarrassing all the French nobles who were suckered by a peasant girl from Toulouse. Therese and her husband each did five years of hard labor. Afterward, she disappeared from the history books, although it is thought she immigrated to the United States.

5 The Murder Of Eugenie Fougere

Eugenie Fougere, part of the Parisian demimonde, was a frequent guest at France’s most lavish casinos. Therefore, her murder on September 20, 1903, made headline news all over Europe.

Eugenie Fougere had checked into a luxury villa in the spa town of Aix-les-Bains. She was accompanied by two female servants. One of them was strangled like her employer, while the other one, Victorine Giriat, was found bound and bloodied. Like many women of her standing, Fougere had the habit of putting a significant amount of her wealth into jewelry which she carried with her, thus making her an attractive target for thieves.

That was what happened according to Giriat. However, authorities weren’t so quick to dismiss her as a simple victim and had her followed over the next few days. She went back to Paris, where she started gambling heavily and confessed to her involvement to several associates. Police arrested her, and after a few hours of interrogation, Giriat confessed to her complicity in the murders. She pointed to a man named Henri Bassot as the mastermind and another one called Cesar Ladermann as the killer.[6]

The latter committed suicide before being arrested, while the former had a solid alibi for the night of the murders. However, investigators found correspondence which showed that, although Bassot wasn’t there, he carefully planned out the operation, which his accomplices carried out.

4 The Execution Of Auguste Neel

Auguste Neel’s crime, while still heinous, wasn’t particularly noteworthy. One December night in 1888, Neel and fellow fisherman Louis Ollivier got drunk and broke into a boat cabin which they thought would be empty. The captain, however, was there and tried to defend himself. The duo stabbed him to death and, in a poor attempt to conceal their crime, also dismembered the body. They were soon arrested, and Neel got the death sentence, while his partner received ten years of hard labor. What stood out about this event were the efforts the authorities went to in order to give the fisherman the official French execution. Auguste Neel remains, to this day, the only person guillotined in North America.[7]

Neel lived in Saint Pierre and Miquelon, a small archipelago off the coast of Newfoundland. Today, it remains the only French territory in North America. The problem was that Neel was going to be their first execution, and they didn’t have a guillotine. Still, local government was keen to obey French law, which meant that they couldn’t just hang or shoot him. They also couldn’t ship Neel someplace else because the execution had to be near the site of the crime. Eventually, they had to import a guillotine from Martinique.

The device arrived broken and had to be rebuilt. They had no executioner, so they hired a recent immigrant to do the deed. The blade was dull, so it only went through part of Neel’s neck. It was a fiasco from top to bottom, but that guillotine became one of Saint Pierre’s most popular tourist attractions.

3 Lebiez And Barre

In April 1878, the landlady of the Hotel Jeanson in Paris made a gruesome discovery in one of the rooms—a pair of severed arms and a pair of severed legs wrapped up in a parcel and hidden in a cupboard. The torso and head were missing.

Thanks to an old wound, police identified the victim as Madame Gillet, a milkwoman. The room had been rented under the fake name “Emile Gerard.” Eventually, the rest of the decaying body was found in a portmanteau left at a railway station warehouse. It was traced back to Aime Barre, a local stockbroker facing bankruptcy, who was also identified as “Emile Gerard” by the landlady.[8]

Barre was arrested, but he also denounced a friend named Paul Lebiez as an accomplice. Lebiez was actually a highly respected medical student who gave lectures on Darwinism. In fact, critics of Charles Darwin used Lebiez as a negative example of what happened when people embraced the idea of only the strong surviving, or the “theory of vital competition,” as Lebiez referred to it in his lectures.

Both criminals tried to blame the other one for the murder, but in the end, they faced the guillotine together on September 7, 1878.

2 The Monte Carlo Trunk Murder

There was a time when Vere Goold was a prominent member of the Irish gentry. He was very proficient at tennis and, in fact, won the first ever Irish Open in 1879. He failed to defend his title the next year, though, and his career went downhill from there.

By the mid-1880s, he’d married a French dressmaker named Marie Giraudin. The two lived lavishly in London and soon were steeped in debt, so they relocated to Montreal and then to Liverpool. In 1907, the couple decided they would break the bank at Monte Carlo. They didn’t, so on August 5, the Goolds were going back home with a stop in Marseille. They had a heavy trunk which they left in the care of a clerk and another stuffed kitbag which they took with them.

While attending to the trunk, the clerk noticed a foul smell and red liquid seeping out of it. He went to the hotel and confronted the couple. They first attempted to convince him that the blood was from slaughtered chickens, and when that didn’t work, they tried to bribe him. Instead, the clerk notified the police. Marseille authorities opened the trunk and were shocked to discover the torso and severed arms of a woman. Her head and legs were found in Vere Goold’s kitbag.[9]

French police determined the victim to be Emma Levin, a rich widow who loaned the Goolds money in Monte Carlo. Initially, Vere tried to take the blame, but authorities believed he was a henpecked husband bullied by an overbearing wife. Criminologist Alexandre Lacassagne called him “murderer as victim.” He got life in prison but committed suicide shortly after. Marie was sentenced to death but died of fever before being executed.

1 The Steinheil Affair

Marguerite Steinheil was a celebutante in her day, known for her numerous affairs with important men. Undoubtedly, her most infamous dalliance was that with French president Felix Faure, who allegedly died while having sex with Steinheil in his office in 1899. But even this scandal seemed tame in comparison to an event which happened at Marguerite’s residence on May 31, 1908.

That morning, a servant named Remy Couillard found her bound and tied to a bed. Her husband, painter Adolphe Steinheil, and her mother were found murdered. According to Marguerite’s testimony, four strangers wearing black robes woke her up, mistaking her for her daughter, Marthe, demanding to know where her parents kept the money and jewelry.

At first, the police took Madame Steinheil’s statement at face value, although the press was a bit more incredulous. Authorities acted with the belief that the mastermind was one of her husband’s former models, but this avenue of inquiry never led anywhere.

After almost six months of investigation, Marguerite tried to frame the servant Couillard by planting a pearl allegedly stolen that night on him. However, a jeweler proved she was lying, as the pearl was in his possession at the time of the murders. She then shifted blame to Alexander Wolff, her chambermaid’s son. He had a solid alibi.

Now, Marguerite Steinheil became the main suspect. New clues surfaced which were initially overlooked. Marguerite’s gag had no traces of saliva on it.[10] A witness claimed her bindings were too loose to be genuine. Her mother had her dental plate in her mouth, meaning she wasn’t killed while sleeping, as Marguerite claimed. Madame Steinheil had conveniently sent away her daughter and watchdog that night.

While not conclusive, the evidence was enough to convince the police to charge her with the murders. A sensationalistic trial ensued, in which Marguerite Steinheil was acquitted. A century later, the details of the Steinheil Affair still remain a mystery.

Read about more crimes from Europe’s past on 10 Notorious Highwaymen From European History and 10 Royal Murders That Shocked Medieval Europe.