History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Fascinating Finds And Stories Involving Old Ships

The ocean likes to cull ships. Over the centuries, storms and reefs have amassed a great collection at the bottom of the sea. Wars added plenty more wrecks. When water conditions are right, skeleton crews and cargoes remain preserved for centuries.

Among other things, divers recently encountered included two of the world’s oldest artifacts on the same wreck, a unique barge, and unexpected Englishmen. The most intriguing cases often involve ships that have vanished. From the missing fleets of Columbus to wrecks disappearing from a World War II battlefield, old ships bring a mystery to match every discovery.

10 The Eira Candidate

Benjamin Leigh Smith was a prolific Arctic explorer. The Englishman saw places that nobody had ever seen and had many named after him. In 1881, his ship, the Eira, sank near an archipelago that today is known as Franz Josef Land.

After safely reaching solid ground, he named it for his famous relative Florence Nightingale. A few makeshift cabins at Cape Flora sheltered Smith and his crew for the next six months. They were rescued, and Smith continued with his career, earning prestigious awards and respect from the scientific world.

Despite the honors he received and the achievements that marked his expeditions, Smith was largely forgotten a few decades after his death. To rectify this, researchers spent years hunting for his steam yacht.

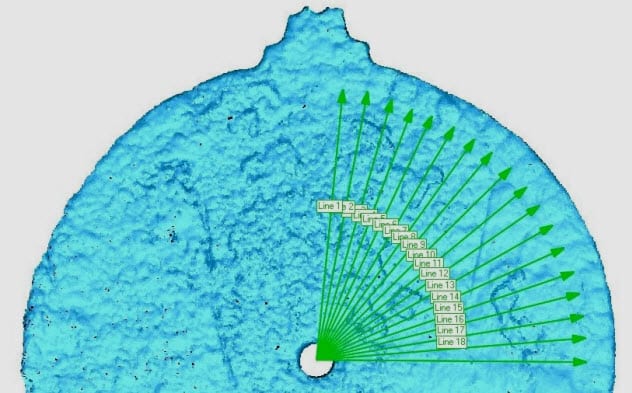

In 2017, a Russian crew surveyed the bottom of the sea at Cape Flora. Scanning equipment located an object the size of the Eira, and video footage gave positive feedback that the wreckage belonged to the yacht. If confirmed, the return of the Eira could help put Smith back on the map.[1]

9 Sea Champagne

In 2010, divers explored the seafloor off the Finnish Aland archipelago. They found a shipwreck with 168 wine bottles. The 170-year-old beverage turned out to be champagne. Some ended up in the divers’ digestive systems, and the rest made it to a laboratory.

Surprisingly, the wine’s chemical composition closely matched that of modern champagne. But there were differences. The 19th-century wine reflected the era’s sugar worship. Today’s brands contain as little as 6 grams per liter (0.8 ounces per gallon), whereas the shipwreck bottles had a stiff dose of 150 grams per liter (20 ounces per gallon). It also contained more table salt, copper, and iron.

Cork engravings suggested that the wine came from French champagne houses Heidsieck, Juglar, and Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin. The delivery was delayed by the ship’s demise, but the ocean’s conditions mimicked the perfect wine cellar.[2]

At 50 meters (160 ft) deep, the constant dark and low temperatures aged the wine surprisingly well. Wine tasters described it as “smoky, spicy, with floral and fruity notes” before taking the “smoky” further with flavors like “grilled and leathery.” Overall, a tasty bubbly.

8 Diverse Mary Rose Crew

Over the years, historians populated Tudor England with white people. However, when the Mary Rose was discovered, the warship presented a strong case for a multicultural Tudor era. She was King Henry VIII’s flagship which sank in 1545 during the Battle of the Solent.

The wreck was raised in 1982 along with 30,000 artifacts and bones. The Mary Rose Trust cleaned and cataloged them for years. They recently focused on eight skeletons enigmatic enough to suggest that the warship’s crew and, by extension, perhaps Tudor England were very diverse.

DNA tests and artifacts proved that at least four were not white English.[3]

One was a Spaniard employed as a ship’s carpenter. There was also an Italian with valuable possessions, including a figurine manufactured in a Venice workshop. Another had African ancestry (northern Sahara), but researchers are almost certain that he was born in England. The fourth man was a Moor with roots along the North African coast. He was no casual passenger. The Moor was a royal archer and likely belonged to the King’s Spears, Henry VIII’s private bodyguards.

7 The Missing Miniature

When Howard Carter found Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922, the treasures stunned the world. Among the artifacts were model boats meant to be used by Tutankhamen (1341 BC–1323 BC) as transportation in the afterlife. After Carter removed them, the vessels ended up in the Luxor Museum in Egypt. By 1973, one miniature ship was officially missing.

In 2019, Mohamed Atwa, one of the museum’s directors, prepared for an exhibition. He felt the display could do with some Tut artifacts and rooted through the archives.

In one of the storerooms, Atwa found a box. Inside layers of newspapers rested pieces of a model boat. Atwa recognized the wooden parts at once. The rigging set, mast, and gold-wrapped head matched another tiny vessel from Tutankhamen’s tomb.[4]

The newspapers were printed in 1933, which was probably the year that the miniature ship went missing. Not from mischief but because somebody forgot to record that they had repacked the artifact and moved the box.

6 The Moving Ghost Fleet

In 2017, a group of fifth graders visited Mallows Bay in Maryland. They looked at 200 wrecks from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and both World Wars. Over the years, the vessels were sunk on purpose. But today, they mesh together an artificial ecosystem for several species.

The children, ages 10 and 11, wanted to know more about the so-called ghost fleet. They pored over aerial maps marking the locations of the wrecks, looking specifically at maps compiled decades apart. The children wanted to see whether any ships had fallen apart or moved.[5]

The maps showed that the fleet was partially on the move. Some had scooted far from their scuttling positions, moving downriver by as much as 32 kilometers (20 mi). The inquisitive youngsters also found the reason. Over time, sometimes centuries, the wrecks got nudged along by floods and storms.

5 Oldest Bell And Astrolabe

In the maritime tradition, the name Vasco da Gama is well-known. A lesser-known fact is that the Portuguese explorer’s uncle was a pirate. Vicente Sodre captained the Esmeralda, an armed ship assigned to protect Portugal’s trading interests.

In 1502, Sodre sailed with an armada to India. Then he went his own merry way to loot and destroy Arab ships. The following year, a storm sank the Esmeralda in Oman. There she stayed unnoticed until 1998, although excavation didn’t begin until 2013.

Subsequent dives returned to the surface with a fractured ship’s bell and something resembling an astrolabe. The latter was an exceptionally rare navigation device. It was a bit messed up from all the years under the sea, but scans revealed the now-invisible marks that once helped mariners to navigate. Analysis also placed the disk’s manufacturing date around 1496.

This was significant. Not only was it rare but the tool was also the oldest of roughly 100 astrolabes still in existence. Incredibly, the ship’s bell was also the earliest ever discovered. It was dated from an inscription that included the year 1498.[6]

4 Titanic‘s Fire Damage

The RMS Titanic was on fire before it collided with an iceberg. When the liner departed from Belfast, Northern Ireland, and sailed for Southampton, England, coal bunker No. 6 was already smoldering.

Ship officials knew of the problem and struggled for three days to bring the fire under control. After the ship sank, the fire was brought up at the original inquiry. However, the incident was played down and the official ruling stated that the tragedy was caused by “an act of God.” New evidence suggests that criminal negligence was to blame.[7]

In 2017, an investigator found new photos of the Titanic showing dark areas on the hull—specifically, near bunker No. 6 where the future iceberg would cause the worst damage. If the investigator’s calculations are correct (he spoke with metallurgy experts), the fire lit the hull to a hellish 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,832 °F).

This sapped up to 75 percent of the metal’s strength. This frailty amplified the collision’s damage. Healthy panels might have slowed or prevented the unexpected sinking of the Titanic.

3 The Columbus Mystery

The Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria became infamous after they carried Christopher Columbus to the New World in 1492. Their discovery would be unequaled by any other.

Despite decades of searching, nobody has found a single splinter. Columbus wrote that the Santa Maria hit a reef off Cap Haitien, Haiti, in 1492. The crew used the hull to raise a fortified village called La Navidad (also missing). There is no sign of the Santa Maria in the Caribbean, where teredo worms can consume a wooden wreck within years. The area was also trampled by 500 years’ worth of tropical storms—not good weather for a ship that went down in shallow waters.

Modern technology like sonar also fails to detect ships buried under centuries-old layers of sediment. The ships contained little metal as well, making a critical ship-finder tool, the magnetometer, useless. No record exists of what happened to Nina and Pinta after they returned to Europe. For that matter, Columbus sailed three more times with new fleets and none of those ships were found, either.[8]

2 Mysterious Baris Found

Herodotus, a famous Greek historian, once described a ship. While moseying through Egypt in 450 BC, he watched the construction of a barge. Called a baris, it had a single rudder that passed through an opening in the keel, a mast of acacia wood, and sails from papyrus.

Herodotus wrote about planks cut in 100-centimeter (40 in) pieces and stacked like bricks. He described beams stretched over certain areas and seams sealed from within using papyrus. Archaeologists had never seen such a boat.

In 2000, an epic find revealed the submerged city of Thonis-Heracleion off the Egyptian coast. Among the ruins were over 70 ancient vessels. Ship 17 might have a boring name, but it was Herodotus’s elusive baris.[9]

His writings described Ship 17’s unusual architecture. In turn, this explained enigmatic descriptions like “long internal ribs” which nobody understood until they saw Ship 17. Originally measuring 28 meters (92 ft) long, it revealed why the barges vanished. This baris was reused as a jetty, suggesting that the barges were incorporated into other structures as soon as they outlived their usefulness.

1 Missing World War II Wrecks

During World War II, the Battle of the Java Sea was fought between the Allied forces and the Imperial Japanese Navy near Indonesia. Several ships from Britain and the Netherlands were lost as well as a submarine from the United States.

In 2016, the area was scanned with sonar. To the outrage of many, Dutch vessels HNLMS De Ruyter and HNLMS Java as well as the British HMS Exeter and HMS Encounter had completely disappeared. Significant portions were also missing from the HMS Electra and HNLMS Kortenaer. The submarine, the USS Perch, was also nowhere to be found.

The region is lucrative for those stealing scrap metal. Indeed, illegal scavengers have been known to disguise themselves as fisherman and blow shipwrecks apart with explosives. This treatment sparked the outrage—the ships that sank in 1942 were also the war graves of hundreds of sailors.[10]

However, the plot thickened when legal salvage companies and even Indonesian naval representatives claimed that the ships were too large and deep. Any attempt would require cranes, manpower, and months of activity, making a stealthy steal impossible.

Read more fascinating stories about old ships on 10 Sunken Ships With Unusual Stories To Tell and Top 10 Remarkable Finds Involving Old Ships And Explorers.