Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

10 Amazing Facts About The Unkillable Soldier

History is littered with the exploits of tough, durable, and seemingly unkillable men. Ivor Thord-Gray paid tribute to his Swedish Viking forebears by serving the British Empire as a member of the Cape Mounted Riflemen during the Second Boer War, fighting Filipino insurgents as a member of the US Foreign Legion of the Philippine Constabulary, fighting for republicanism in China and Mexico, fighting on the Western Front in World War I as a member of the Northumberland Fusiliers, and then finally fighting Bolshevism as an officer in both the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force and the Russian White Army.

Another tough grunt was the humble Portuguese farmer Anibal Milhais, who used his Lewis light machine gun to single-handedly halt a German offensive near the French village of Isberg during World War I. Not to be outdone, US Special Forces soldier Roy Benavidez managed to survive a six-hour battle in South Vietnam after sustaining seven gunshot wounds, 28 fragmentation wounds, and two bayonet slashes to his arms. Canada produced its own “Rambo” in the form of the Massachusetts-born and French-speaking Leo Major, an army sniper who liberated the city of Zwolle, Netherlands, all by himself in World War II and then earned an unprecedented second Distinguished Conduct Medal for helping to capture and hold Hill 355 during the First Battle of Maryang San in 1951.[1]

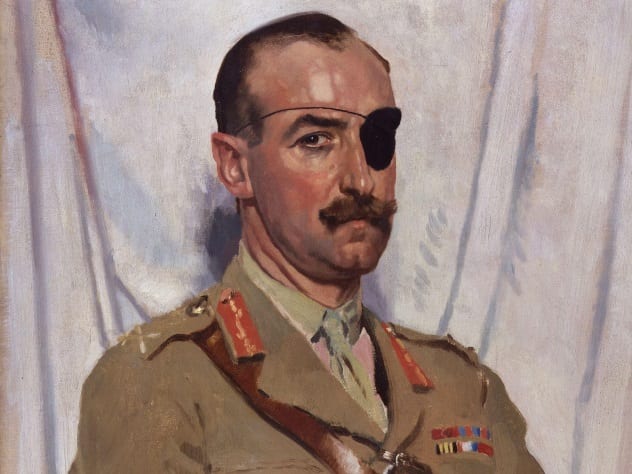

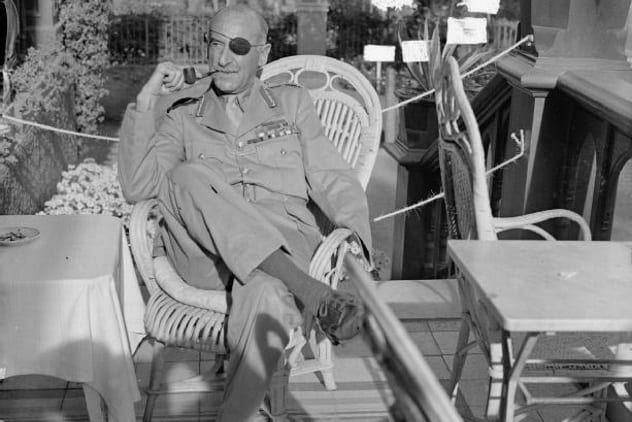

Standing tall above them all was a truly unkillable soldier—a nobleman and veteran of several wars—Adrian Carton de Wiart. Across multiple wars, de Wiart would sustain 11 different wounds, any one of which would have killed a weaker man.

10 Europe’s Last Knight

Belgium has always been known as a little land of chocolate, beer, and frites. What many do not know is that Belgium has also produced great warriors. King Albert I, who took command of the Belgian military in August 1914 and in 1918, would become one of the last royals to personally lead troops in battle. Other Belgian fighters include the African mercenary Jean Schramme, RAF fighter pilot Jean de Selys Longchamps, Free Belgian leader Jean-Baptiste Piron, and Lieutenant General Charles Tombeur, the man who decisively won the East Africa Campaign for the Entente in World War I.

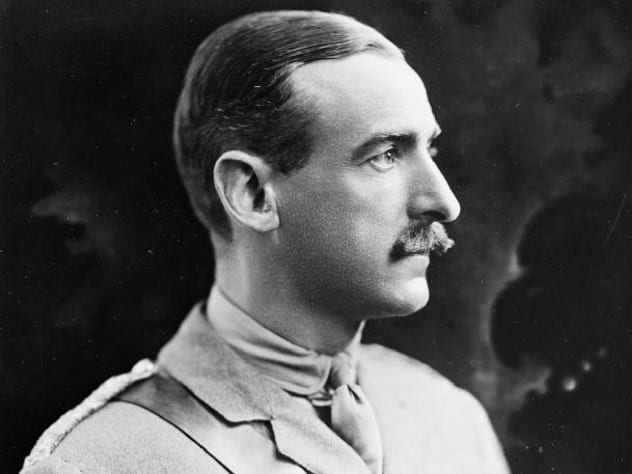

Out of this milieu came Adrian Carton de Wiart. Born into an aristocratic family in Brussels on May 5, 1880, de Wiart was the son of a Belgian lawyer who was the director of Egypt’s Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company. De Wiart’s mother was an Irish Catholic, but for the majority of his life, de Wiart was raised by his English stepmother. It was his stepmother who sent de Wiart to school in England.

After studying law at Oxford University, the Belgian nobleman decided to pursue a more interesting life abroad. Like a generation of Belgians before him, de Wiart went to Africa. But, rather than land in the Congo Free State, which was then the private property of King Leopold II, de Wiart traveled to British South Africa as “Trooper Carton” in order to find war.[2]

9 The Second Boer War

After lying about his age in order to enlist in the British Army, de Wiart found himself in South Africa in 1899. In that year, the infamous Second Boer War broke out between the British Empire and the Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. During the war’s first year, the British Army, which was then considered the best-equipped and best-trained field force in the entire world, was embarrassed by Boer militiamen, who called themselves “commandos.” Between late 1899 and early 1900, the Boers scored impressive victories at Magersfontein, Colesberg, and Stormberg, while simultaneously laying siege to Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking. The successful guerrilla warfare of the Boers would eventually lead to the British use of concentration camps, whereby Boer women and children were housed in filthy, disease-ridden camps.

During his first tour of duty in South Africa, de Wiart was shot in the stomach and groin. These wounds proved serious enough that he was shipped back to England in order to recover. Undeterred, de Wiart returned to South Africa in 1901 and joined the Imperial Light Horse, one of the best regiments of Britain’s Colonial Corps.[3] The enlisted de Wiart impressed his superiors so much that he became a commissioned officer in 1902. De Wiart’s first assignment as an officer was British India, the time-tested proving ground for all British men-at-arms. Two years later, de Wiart was back in South Africa. While there, de Wiart finally became a British subject.

8 The Somaliland Campaign

The peacetime years were productive for de Wiart. Namely, in 1908, de Wiart married Countess Friederike Maria Karoline Henriette Rosa Sabina Franziska Fugger von Babenhausen, an Austrian noblewoman and a member of a clan of wealthy bankers. Despite this marriage, and despite becoming a father of two daughters, de Wiart never mentions either his wife or girls in his 1950 autobiography, Happy Odyssey. For de Wiart, war was everything.

When World War I broke out in 1914, de Wiart was seconded to the Somaliland Camel Corps, a new unit composed of physically fit Somali soldiers commanded by British officers. As the name would imply, the Somaliland Camel Corps often went into battle on camels.

The unit’s main task was to defeat the Dervish State, a breakaway polity ruled by the Islamist warlord Mohammed Abdullah Hassan. The man the British, Italians, and Ethiopians called the “Mad Mullah” successfully brought thousands of tribal fighters to his cause. These fighters managed to harass the British and Italians for 20 years.

On November 17, 1914, the Somaliland Camel Corps attacked the Dervish fort at Shimber Berris. The attack was repulsed, and de Wiart was shot in the face during the action. These wounds would later cost de Wiart his left eye and part of his left ear.[4] Once again, de Wiart was sent back to England in order to recover. On May 15, 1915, de Wiart was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

7 The Western Front

While recuperating in England, de Wiart made it clear to his doctors and nurses that he wanted to go to the Western Front. De Wiart got his wish in February 1915, as he landed in France to take charge of an infantry battalion.

Beginning on April 22, 1915, and lasting until May 25, the Second Battle of Ypres was one of history’s most awful meat grinders. The battle is best known as the first instance where the German Army deployed chlorine gas in an effort to break through the British, French, and Belgian defensive lines. As per custom on the Western Front, the Germans opened all of their attacks with heavy artillery barrages. The engagements near Ypres were no different. It was during one of these battles that de Wiart suffered severe damage to his left hand after it was struck by a German shell.[5] Army doctors refused to amputate the hand. What did de Wiart do? He simply tore off two of his fingers and returned to the battle.

In 1916, de Wiart led a British infantry unit during the infamous Battle of the Somme, which was a massive Entente offensive that would ultimately cost 1.5 million men. The British alone suffered 57,000 casualties on the first day (July 1, 1916). De Wiart was one of these casualties, as the young officer was shot in the head and ankle. These wounds did not stop de Wiart, and in subsequent battles of the Somme Offensive, de Wiart was shot in the hip, leg, and right ear.

6 The Victoria Cross

There is no higher award in the British military than the Victoria Cross. De Wiart would join the ranks of the British immortals during the Battle of La Boiselle in 1916. During that action, de Wiart was in charge of the 8th Gloucestershire Regiment. Between July 2 and 3, de Wiart and three other officers led a bayonet charge across No Man’s Land. When the other officers died, de Wiart took command of all four British battalions and gave orders to all his men by waving around his walking stick.[6] Keep in mind that de Wiart did all of this while German machine guns cut down his men and others.

Incredibly, Happy Odyssey makes no mention of winning the Victoria Cross. Despite becoming a legend and a hero while he was still alive, de Wiart proved to be a modest man who simply wrote off his battlefield accomplishments as part and parcel of his enjoyment of war.

5 Fighting The Bolsheviks

The fighting ended on the Western Front in 1918, but the war raged on elsewhere. Even as European and American diplomats met to hash out the Peace of Versailles in 1919, Eastern and Central Europe were still in flames. No battlefield was bigger in 1919 than Poland.

Born out of the collapse of the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires, the Second Polish Republic was surrounded by enemies. In January 1919, Polish soldiers, many of them veterans of the German, Austrian, Russian, and even French armies, fought scattered street battles with Bolsheviks in the Lithuanian city of Vilnius. For the Poles, taking Vilnius was all about securing borders. For the Bolsheviks, capturing Vilnius was about pushing the Bolshevik Revolution westward.

Poland reached out to Britain and France in order to gain support in their war against Communist Russia. In 1919, the British-Polish Military Mission went to Poland in order to settle the fighting there. One of the army officers in this mission was none other than Adrian Carton de Wiart. De Wiart, who briefly replaced General Louis Botha (himself a Boer War veteran) as the British mission’s leader, had the unenviable task of creating a lasting peace between the Poles and Ukrainian nationalists led by Simon Petlyura.

De Wiart was a better soldier than a peacemaker, and while in Poland, he became a partisan of the Polish cause. He became involved in a gun-running plan out of Budapest, Hungary. Also, de Wiart would second a duel in Poland that also involved General Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, the future leader of Finland during World War II. Sometime in 1919, de Wiart was briefly a prisoner of war after his second plane crash found him in enemy hands in Lithuania.

In the summer of 1920, de Wiart was named aide-de-camp for the British king and advanced to the temporary rank of brigadier general. Despite this, de Wiart was always close to the fighting. In August 1920, Red Army Cossacks attempted to capture an observation train that de Wiart was traveling on. De Wiart fought the Bolsheviks throughout the day and into the night. His only weapon was his service revolver.[7]

The Polish-Soviet War came to an end following the “Miracle on the Vistula,” where between 113,000 and 123,000 Polish soldiers defeated a 140,000-man Red Army force commanded by General Mikhail Tukhachevsky. Rather than return to England, de Wiart decided to remain in Poland. For 15 years, de Wiart lived at a hunting lodge on the property of his friend, Prince Karol Mikolaj Radziwill. De Wiart would write decades later that he spent his years in Poland hunting.

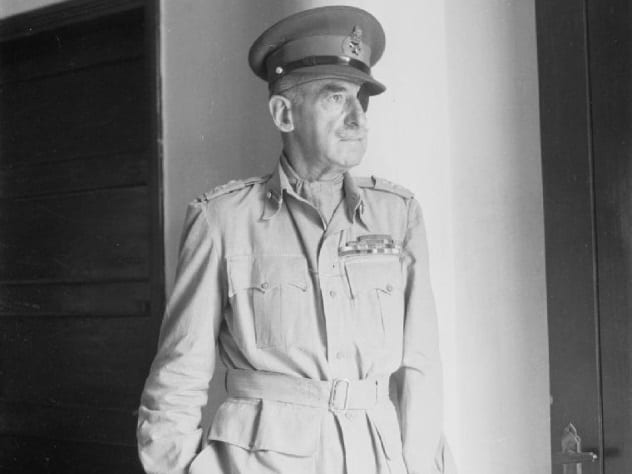

4 Back In Service

De Wiart left the British Army in 1923 as a major general. When Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin invaded Poland in 1939, de Wiart found himself once again in the thick of it. Not only did the Nazis blow up de Wiart’s house, but as the general drove through Poland en route to safety, the Luftwaffe strafed his vehicle.[8] Before leaving Poland for Romania, de Wiart tried to convince Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly to move his men beyond the Vistula River, but de Wiart’s suggestion was rejected.

The Polish military did, however, listen to de Wiart when he suggested that the Polish fleet leave the Baltic and head for the UK. This move would prove important, for the Polish Navy would be absorbed by the British Royal Navy in 1939 and would distinguish itself by sinking 12 enemy ships.

Once in Romania, de Wiart wasted no time in rejoining the British Army.

3 Norway And Yugoslavia

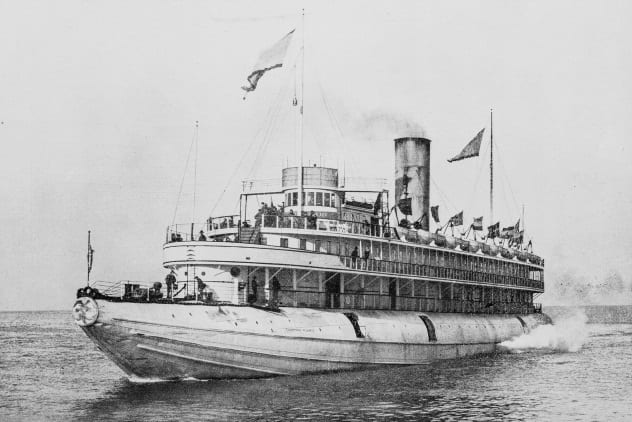

De Wiart’s first mission in World War II saw him take part in the failed Anglo-French effort to halt the Nazi takeover of Norway. Even before de Wiart set foot in Norway, his seaplane was forced to land in an isolated fjord after being attacked by a Luftwaffe fighter. Rather than become a sitting duck in a rubber dingy, de Wiart waited until the German plane ran out of ammunition and then casually walked aboard the rescue boat that eventually reached his position.

During the Namsos Campaign of 1940, de Wiart managed to get his men to march over the mountains and take Trondheimsfjord. Somehow, despite the fact that de Wiart and his men were shelled by German naval guns, shot at by German ski troops, and strafed by Luftwaffe fighters, they managed to hold their positions until de Wiart finally gave the order to withdraw.

For a time, de Wiart licked his wounds and stewed over the botched Norway Campaign. Then, in April 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill named de Wiart the head of a British military mission to Yugoslavia. The purpose of the mission was to support the Kingdom of Yugoslavia ahead of a planned Axis invasion. De Wiart never made it to Yugoslavia, however.

After taking off from British Malta in a Vickers Wellington bomber, de Wiart suffered the third plane crash of his life. He and the RAF crew managed to survive the crash landing in the Mediterranean by hanging out on the plane’s wings. It was the 61-year-old de Wiart who convinced everyone to swim to the nearest shore. The nearest shore just happened to be Libya, which was then under Italian control.[9]

2 Great Escape

De Wiart was one of 13 high-ranking British officers who the Italians kept inside Vincigliata Castle outside of Florence. These old soldiers, including British general Sir Richard O’Connor, the man who came close to defeating Mussolini’s army in North Africa in 1940, had no intention of waiting out the war behind bars. De Wiart and the others began devising ingenious methods of escape. These methods included climbing down into an ancient well, using a homemade rope to scale the castle’s walls, and drilling holes into the castle’s walls.

Eventually, the men dug an 18-meter (60 ft) tunnel straight through the castle’s bedrock foundation. The entire ordeal took seven months. In March 1943, the men split into three teams of two and escaped. Some rode the Italian railways in an attempt to reach Switzerland. De Wiart and O’Connor tried to walk to Switzerland. This great escape lasted just eight days.[10] De Wiart would not be free again until August 1943, when, following the removal of Benito Mussolini from power, de Wiart’s Italian captors dropped him off in the neutral city of Lisbon, Portugal.

1 Asia And The End

Old and battle-scarred, de Wiart returned to the war in December 1943. This time, he was named as a special representative of the British Army. His first and last posting was China, where de Wiart served as an aid to General Chiang Kai-shek until 1946.

During this time, de Wiart was mostly tied down with administrative duties in the wartime capital of Chongqing. That said, de Wiart was known to travel to India in order to liaison with British officers then busy fighting the Japanese in the northeastern part of the country. While the war was still raging in Asia, de Wiart, who was involved in negotiations between Chiang’s nationalist forces and Mao’s communist fighters, reportedly criticized Mao and his communist ideology to the future chairman’s face. In particular, de Wiart, a devout anti-communist, criticized Mao for not fighting the Japanese.

In August 1945, de Wiart was on hand for the formal surrender of the Japanese forces to the British at Singapore. Before retiring from service in October 1947, de Wiart briefly lived in the city of Nanking, which had been the site of the infamous Japanese “rape” in 1937. De Wiart managed to get into one last scrape, this time in Rangoon, Burma. Here, de Wiart fell down a flight of stairs, which ended in a broken vertebra.[11]

De Wiart retired to County Cork, Ireland, for a brief spell, and it was there that he was knighted. De Wiart died at the age of 83 in 1963. His list of awards and honors include: Victoria Cross, Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Companion of the Order of Bath, Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, Officer of the Belgian Order of the Crown, the Belgian Croix de guerre, Knight of the Order of Military Virtue of Poland, the Cross of Valor (Poland), the French Croix de guerre, and the Legion of Honor (France).

Read about more incredible soldiers on 10 Real-Life Soldiers Straight From An Action Movie and 10 Famous People Who Were Secretly Badass Soldiers.