Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

10 Of The World’s Most Mind-Blowing Hoaxes

Most of us have been there. In a moment of weakness—or perhaps glory—we are given a choice. Do we leap at the chance to curate the ideal version of our collective story, or do we accept the reality before us?

Some of us balk at the thought of telling a little white lie. What would happen if we were caught? How might we maintain such a deviation from the truth? Or perhaps, if you are the more brazen type, you might leap at the chance to write your own narrative. After all, not all of us are gifted such perfect opportunities to create a new version of history.

In the spirit of such opportunities, we present to you a list of 10 of the world’s boldest individuals—those who saw their opportunity and seized their new reality. Albeit not for long.

10 Amerigo Vespucci

Have you ever wondered where the Americas got their current namesake? Not from the man who first brought their existence to the attention of the Western world, but from a man who wrote enough letters to play his cards right.

Born to a prominent Florentine family at the height of Europe’s Age of Exploration, Amerigo Vespucci tried his hand at many trades. He briefly worked as a diplomat for his Uncle Guido, who was the French ambassador of Florence. Then Amerigo became a banker under the Medici family in Seville, Spain. Finally, he decided to pursue exploration in the name of fame and legacy.

According to one of Vespucci’s letters, after meeting Columbus, Vespucci and a Spanish fleet sailed to Central America over the course of five weeks and effectively landed upon Venezuela a full year before Columbus. In a time when fact-checking was much more laborious than the click of a few buttons, many individuals relied solely on these accounts written in Vespucci’s letters.

However, modern historians doubt the authenticity of Vespucci’s claims and the number of voyages that he actually took. As it so happened, a German cartographer was putting together a book of maps in 1507. Having previously heard of Vespucci’s letters, he decided to name the southern continent of the New World “America”—the feminine version of “Amerigo.”[1]

In 1538, another cartographer decided to name both continents “America.” Thus, Amerigo Vespucci was ever glorified as the lead contributor to the establishment of the West in the Americas.

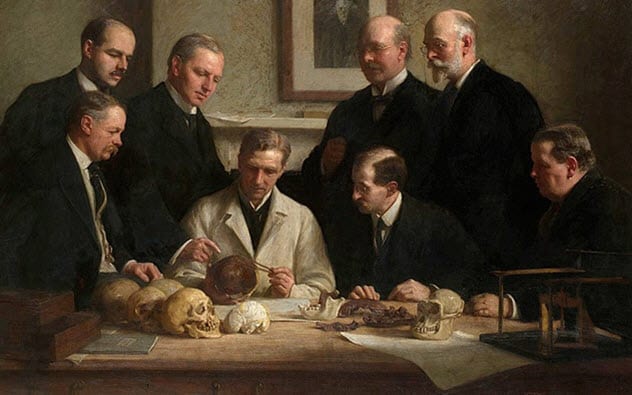

9 Piltdown Man

Charles Dawson And Arthur Smith Woodward

Since Charles Darwin’s assertion of evolution became popular in the 19th century, archaeologists have been on the search for the “missing link” between ape and man. In 1912, this link was finally found in a gravel pit in Piltdown, Sussex, United Kingdom.

Discovered by amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson, this missing link was a monumental step for the research of human evolution. When he found it, Dawson wrote to Arthur Smith Woodward, the Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum, and excitedly proclaimed that more bone fragments could be found.

Indeed, more fragments were unearthed in the area, including a set of teeth and a mandible, primitive tools, and other crucial bone fragments. How serendipitous these discoveries were. For, in 1907, a German sand mine worker had found the jawbone of a hominid that was 200,000–600,000 years old.

With rising tensions between Germany and England, it was indeed fortunate that Dawson had made his discovery. However, as the unearthing of hominid fossils became more prominent, it was increasingly clear that something was off about Dawson’s finds.

In 1953, new techniques of fluorine dating allowed University of Oxford scientists to more accurately date Dawson’s bones. Alas, it was revealed that the ages of Piltdown Man’s bones were not consistent. In addition, the remains—actually a 50,000-year-old human skull and an orangutan’s jaw—had been carefully carved and stained to fit together.[2]

Over the next approximately 60 years, there was much speculation pertaining to the group behind such a forgery. In 2009, when DNA analysis and carbon dating could be applied to the bones, scientists were able to conclude that the most likely mastermind behind the hoax was Charles Dawson himself.

8 The Great Diamond Hoax

1872

The hype of the 1849 California Gold Rush attracted miners, bankers, and businessmen from all around the globe. Many of these men were honest workers hoping to hit a lucky streak that would make possible their family’s wildest dreams. Others, such as cousins Philip Arnold and John Slack, sought to make their profits from the naivete of others.

Spurred on by the 1870 diamond rush in South Africa, the Kentucky-born cousins plotted to establish a mine that would yield diamonds—right in the middle of Colorado. That year, Philip and John tried to deposit a bag of uncut diamonds at a San Francisco bank. But upon questioning, the two disappeared in a hurry.

William Ralston, a director of the bank, heard of the men and thought that he might be able to make the business deal of a lifetime: Find out where these backcountry cousins had gotten the diamonds, and buy the mine for himself.

What he didn’t anticipate was that Philip and John had a scheme of their own. The two men had “salted” a mine in Colorado to make investors believe that they had stumbled upon a diamond mine.

Subsequently, Ralston founded the New York Mining and Commercial Company and invested $600,000 in the cousins. This company—comprised of prominent individuals such as the founder of Tiffany & Co., a former commander of the Union Army, and a US Representative—sold stock totaling $10 million.

In 1872, the gig was up when new-to-the-scene geologist Clarence King began his investigations. Upon discovery of the secret mine, King noticed that the seemingly random layout of diamonds and rubies was too neat to be natural and was only found in previously disturbed ground.

On November 26, 1872, King published a letter in The San Francisco Chronicle declaring his findings. As a result of this revelation, King became the first director of the United States Geological Survey. Meanwhile, Ralston was only able to return $80,000 to each investor in the company. Slack and Arnold disappeared entirely with their $600,000.[3]

7 ‘The War Of The Worlds’ Radio Broadcast

1938

On the eve of Halloween in 1938, famed American writer and actor Orson Welles released a radio broadcast of his version of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds. Hoping to stir up some excitement, Welles decided to introduce the story as a sudden interruption to the normal evening program.

Prior to airing, Welles and his cowriters had decided to remove many clues throughout the broadcast that would remind listeners of its fiction. They believed that these clues were unnecessary given the clearly implausible nature of the plotline.

So, at 8:00 PM, the evening broadcast began as it always had. However, within 10 minutes, “The War of the Worlds” radio broadcast was launched. Although Welles began the program with a short introduction, many viewers tuned in late and only heard the interrupting news broadcast asserting that an alien invasion was taking place at that very moment.

As the meteor carrying the Martians had supposedly landed in a crop field in Grovers Mills, New Jersey, residents near Princeton were the first to engage in mass panic. Thousands believed that their hometown was being invaded and immediately attempted to flee—causing traffic jams and citizens begging police officials for gas masks and other survival gear.

Upon hearing news of the accidental mass hysteria, Orson Welles had to interrupt the broadcast to assure listeners of its fictional origins. Despite this flop, Welles was offered a job in Hollywood and went on to write, direct, and star in Citizen Kane in 1941.[4]

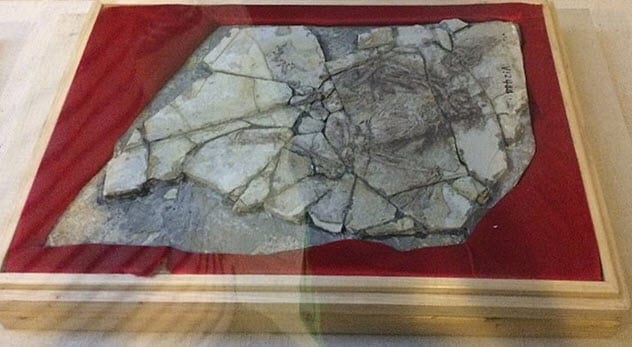

6 Archaeoraptor

Another of paleontology’s most significant findings—the fossilized missing link between dinosaurs and birds—turned out to be a fraud. The Archaeoraptor was introduced to the world in a 1999 National Geographic article that was the first to announce such exciting news to the world.

However, at the time of the article’s release, the fossil was still undergoing a lengthy verification process and had already raised many doubts. The fossil had originated in China and found its way into the possession of a fossil hunter—someone who searches for fossils to sell them as collectibles. He then sold it to Sylvia and Stephen Czerkas, owners of the Utah-based Dinosaur Museum.[5]

Although many doubts concerning the fossil’s authenticity were brought to the attention of the Czerkases, they insisted that any findings other than validation be kept quiet. Shortly after National Geographic published their article on the Archaeoraptor, Xu Xing—a Chinese paleontologist trying to uncover more fossils like Archaeoraptor—found a strikingly similar fossil of the creature’s tail.

In fact, after extensive comparison, it turned out that this fossil was the counter slab of its tail. However, this tail did not properly fit into the hips of the Archaeoraptor.

When paired with revealing X-rays and CT scans of the full skeletal fossil, this finding showed that the tail of the Archaeoraptor and the upper portions of the body did not fit together in any way. Instead, someone had paired together the fossils of a primitive bird and a nonflying dinosaur to create the much-searched-for “missing link.”

5 Tiara Of Saitaphernes

In 1896, the Louvre acquired a priceless new artifact: the Tiara of Saitaphernes. Said to have once been a gift from King Saitaphernes from the Greek colony of Olbia in the third century BC, it was miraculously found in perfect condition and brought to prominence by a Russian art dealer named Schapschelle Hochmann.

The timing of this find could not have been more perfect. Many ancient Greek and Scythian artifacts were being discovered at Russian archaeological sites, and European museums were desperate to attain artifacts of their own.

When Hochmann presented his find in February 1896, the Louvre immediately purchased it for 200,000 francs and put it on display before completing the proper authentication procedures. Despite the doubts of prominent Russian and German archaeologists, the Louvre proudly defended against any critics and negative media attention for the next six years.

However, in 1903, the French magazine Le Matin published an article asserting that Israel Rouchomovsky, a skilled goldsmith from Odessa, was the talent behind Saitaphernes’s tiara. Rouchomovsky was not aware of the deceit concerning his commission.

He only knew what he had been told: that Hochmann had a very particular archaeological friend for whom this crown would be a gift. As such, Rouchomovsky was to base the design of the tiara on the artifacts found at nearby recently excavated sites and to include a particular inscription.

As a result of this scam, Hochmann and the Louvre received massive public backlash. But Rouchomovsky was lauded for his craftsmanship and lived out the rest of his life as a celebrated goldsmith and jeweler.[6]

4 The Cardiff Giant

In October 1869, two local men in Cardiff, New York, were digging a well on the property of William Newell when they discovered the large, petrified body of an ancient man. Thinking that this could be an ancestor of the Onondaga people, the men excitedly spread the news across their town.

However, Newell was reluctant and insisted that the giant be reburied. Luckily, his neighbors encouraged him to reach out to experts and researchers. As news spread, spectators flocked from all over to catch a glimpse of the Cardiff Giant. Many paid a pretty penny to see him in his hole.

As his popularity picked up and the giant created more foot traffic to the area, Newell decided to sell a 75 percent stake in the “petrified man” to a group of businessmen for $30,000. These men promptly took the Cardiff Giant on tour where new eyes—particularly those of experts—scoured the giant for detail.

In fact, upon viewing the giant for themselves, many proclaimed it to be a statue instead of a genuinely petrified man. As word spread of this potential forgery, locals back in Cardiff began to talk among themselves.

Many remembered that George Hull, Newell’s cousin, had transported a large iron crate to the farm a year earlier. Upon further inquiry by reporters, it was determined that Newell had paid Hull a large sum of money promptly after his sale of the giant.[7]

As it turned out, Hull was an atheist who was hoping to simultaneously pad his pockets and disprove a religious belief of some Christians who had argued that the giants in the Bible were real. He paid an artist in Chicago to sculpt a 305-centimeter-tall (10’0″) giant reminiscent of those mentioned in Genesis.

It took him two years to plan and execute one of 19th-century America’s greatest hoaxes and only a few months for it to fall apart.

3 The Dreadnought Hoax

For centuries, Britain had asserted its prowess on the world stage through the power and size of its Royal Navy. But on February 7, 1910, they fell prey to the simplest of schemes.

Horace de Vere Cole, a mischievous Irish poet, decided to round up a group of his closest friends—including famed novelist Virginia Woolf and painter Duncan Grant—for a tour of the most important ship in the British navy: the flagship, HMS Dreadnought.

Just before their arrival, Cole forged an official-looking telegram from the Abyssinian Embassy notifying the commander in chief that a delegation of dignitaries, translators, and Abyssinian princes would be visiting the ship that very day.

In a panic, the commander in chief scrounged together a welcoming party: an official band playing “God Save the King,” African flags flying at masthead, and every sailor on the ship standing at attention.

The “delegation” was comprised of Cole, Virginia Stephen (who had not yet married into the name Woolf), Adrian Stephen (Virginia’s brother), Duncan Grant, and two other writers in the Bloomsbury Group. They boarded the ship dressed in elaborate costumes that fooled the entire crew.

The commander in chief promptly took the delegation on a tour of the ship and listened politely as they exclaimed and remarked in their made-up version of Swahili. Upon the group’s departure, the commander in chief urged them to stay for an elaborate lunch, but they declined due to dietary restrictions. In reality, they were afraid that their fake beards would fall off during the meal.[8]

The next day, the navy was notified of the true identities of their guests and promptly called into question naval regulations surrounding ceremonial parties. By February 12, 1910, the media had found out about the hoax and latched onto the story thanks in large part to Cole writing and circulating a letter detailing the prank.

In response, the Royal Navy sent the Dreadnought out to sea until the publicity blew over. The Bloomsbury Group was not formally charged for the prank due to the navy’s wish to put the bad publicity behind them.

2 Great Moon Hoax Of 1835

The 1800s saw many daring and creative forgers, but the Great Moon Hoax of 1835 is arguably the most successful of them all. On the morning of August 25, 1835, the New York Sun printed the first installment of a six-part science fiction series, except The Sun never specified that the account was fiction.

The tale surrounded a real expedition that the famous astronomer Sir John Herschel had embarked upon a year earlier. Appearing to be a reprint from the Edinburgh Journal of Science, the story released new extraordinary details of Sir Herschel’s discoveries.

Although Sir Herschel had indeed traveled to Capetown, South Africa, in 1834 to set up an observatory for a rather large and powerful telescope, the article’s reports of its size and focus blew the technology wildly out of proportion. The series reported that Herschel had found half-bat humans living peaceably together, a bipedal beaver, one-horned goats, pyramids, and other incredible details that were never before seen through a telescope.[9]

At a time when new technologies and discoveries were abundant, the public was surprisingly receptive to such an article. It certainly helped that the author, Dr. Andrew Grant, had based his story on fact and interwoven bits of hyperbole and fiction throughout.

As a result, confusion ran rampant across the United States and made its way to Europe. Eventually, the author, who had used a pseudonym, admitted that his story was fiction and that he had vastly underestimated the willingness of the public to believe everything in print.

1 The Donation Of Constantine

Perhaps the oldest and most shocking of hoaxes was the discovery of Emperor Constantine’s fourth-century donation of Rome to Pope Sylvester I. The document, which was forged and “discovered” in the eighth century, greatly influenced medieval politics.

As legend has it, Emperor Constantine suffered greatly from leprosy and was miraculously cured of it by Pope Sylvester. Filled with gratitude, Constantine instantly converted to Christianity and declared Sylvester’s papal authority over Rome, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, Jerusalem, and every other church in the world. Only Rome and the churches themselves would be passed on with the succession of Popes.

Flash forward to medieval Europe when church and state were often one and the same. To assert their claim of authority in secular affairs, the Catholic Church often cited Constantine’s document.

However, in 1440, Catholic priest Lorenzo Valla realized that the Latin used in this document was not accurate for the Latin used in the fourth century. The Catholic Church supported Valla’s claim. Since then, the document has not been a part of the Church’s official canon.[10]

Read about more clever hoaxes on 10 Celebrity Death Hoaxes That Almost Had Us Fooled and 10 Clever Hoaxes That Fooled Experts.