Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Factors That Made the Black Death So Deadly

The plague outbreak of the mid-1300s, known widely as the Black Death because of the black, festering sores it produced on the bodies of its victims, was a terrible pandemic. It wasn’t the first outbreak of the plague, but it was far and away the deadliest. Though history tends to focus on its devastation of Europe, the Black Death killed millions in a swath spanning three continents, from the British Isles to Egypt and all the way to China. Estimates of the death toll across the whole of Eurasia range from 75 to 200 million. It reduced the population of Europe by 30 to 60 percent and the population of the world as a whole from an estimated 450 million down to approximately 300–350 million between the 1340s and the mid-1350s.

The impact of the Black Death was so tremendous and destructive that it led Christians to believe they were being punished for their sins. It wiped out entire villages, towns, and cities. It was a depopulation event unlike anything seen before or since. Listed here are ten contributing factors to the lethality of the Black Death.

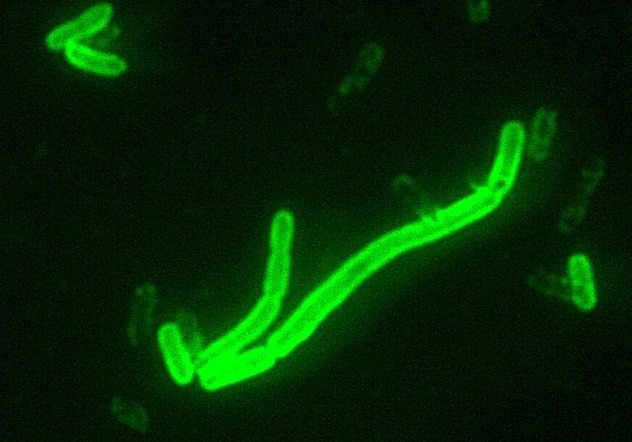

10 Easily Carried by Fleas

For most of its evolutionary history, Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the plague, was no more mobile than Ebola or tuberculosis, so outbreaks seldom occurred, were confined to small areas, and claimed lower numbers of victims. That was back when human-to-human transfer was required for the disease to spread. At some point in recent millennia, a change in the genetic landscape of Y. pestis occurred that gave it some serious wheels: It developed a resistance to toxins in the gut of the flea.[1]

This gave it the ability to spread with and thrive within fleas as they traveled the globe on the backs of rats, cats, and otherwise. With this newfound vector, the Black Death was able to spread far beyond where it had beforehand. The rest is history.

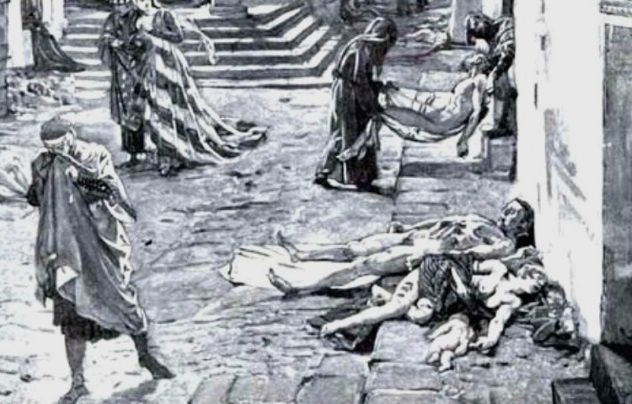

9 Filthy Living Conditions

Imagine a world with no sewers, no running water, and rats. Lots of rats. Where rats are found, fleas tend to follow. In the middle years of the 14th century, the odds were good that many of those fleas carried our good friend Y. pestis. If you were living anywhere in Europe, Asia, or North Africa at the time, the odds were also quite good that you lived in squalor and had little (if any) means of avoiding contact with the plague or anyone infected with it.

In Europe, in particular, people lived in close quarters with one another and often shared their living spaces with all sorts of vermin. They seldom washed, and they lived close to their own filth. Gone were the baths, sewers, and aqueducts of Roman times. Returning to prehistoric levels of filth left the people ripe for infection.[2]

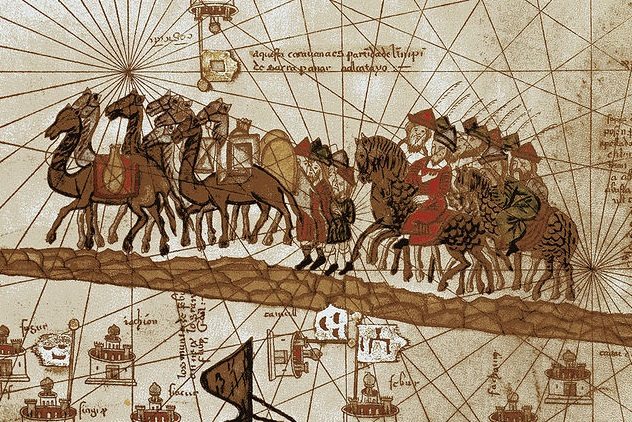

8 The Silk Road

Named for the luxuriant threads spun by the Asian silkworm that merchants carried along its 6,400-kilometer (4,000 mi) span, the Silk Road was founded during China’s Han dynasty. Though the route was a marvel of commerce and diplomacy and allowed for the exchange of goods, languages, ideas, and customs between just about every society from the Atlantic to the Pacific, it also served as a superhighway for infectious diseases.

Historians and epidemiologists alike agree that the plague started somewhere in present-day China or Mongolia and then followed the Silk Road and had reached Crimea by 1346. Though outbreaks of bubonic plague had occurred before in recorded history, most notably in the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century, they hadn’t occurred in a world half so connected as that of the mid-1300s. With the blessings of trade and cultural exchange came the curse of microbial exchange.[3]

7 The Siege of Kaffa

Whereas the Silk Road was a peaceful means by which the Black Death made its way to Europe and Africa, the Mongol conquests of the High Middle Ages were a far more cataclysmic vector. Beginning with the rise of Genghis Khan in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the Mongol conquests took Eurasia by storm. Within the lifetime of Genghis, the Mongols, masters of the horse and composite bow, had laid waste to an unspeakably large swath of land stretching from the Korean peninsula to Hungary. After Genghis Khan died, the empire fragmented into different factions, called khanates, held by his numerous sons.

One of these divisions, the Golden Horde, stretched from Siberia into Eastern Europe. It covered the Crimean Peninsula, in which lay the city of Kaffa. A group of Italian merchants was granted special privileges for the control of Kaffa, which proved beneficial for the Mongols in that it gave them access to European markets. After relations between the Italian merchants and the natives began to deteriorate, the Mongols laid siege to Kaffa.

During the siege, the Black Death began to make its way through the Mongol ranks. Rather than letting the disease get the best of them, they made it work for them. True to form as masters of murderous ingenuity, the Mongols loaded the plague-ridden corpses of their soldiers onto their catapults and launched them over the city walls in an early instance of germ warfare. This, of course, brought the plague into the city, just as the merchants were fleeing back to Sicily.[4] It is generally agreed that the siege of Kaffa was a watershed moment for the expansion of the Black Death into Europe.

6 Climate Change

Many experts argue that climate change, not fleas and vermin, was the preeminent culprit for the deadliness of the Black Death. Whether or not it was the foremost factor, it certainly had a part to play. The onset of the pandemic coincided with the end of the Medieval Warm Period, an era of warmer summers and milder winters lasting from about 900 to 1300. The period allowed for more bountiful harvests and made people less susceptible to illness.

Researchers have determined that this stretch of mild weather was caused by an alteration of global heat distribution through changes in pressure systems. The normalization of said systems pushed much of the Northern Hemisphere back into a cooler, rainier period, which led to lower crop yields and cold, wet conditions that left people far and wide ripe for the plague.[5]

5 Famine

When the Black Death came around, it had the proverbial red carpet rolled out for it to come in and wreak havoc, and famine had a huge part to play in that. In the early years of the 14th century, a period of hunger aptly dubbed “the Great Famine” struck the entirety of the European continent, ranging from Italy to Russia. The famine, which started in 1315, was triggered by an unusually cold winter, which gave way to an unusually cool and rainy spring and a subsequent summer, which followed suit. This, of course, decimated crop yields across the continent, and people were left starving. An estimated 10 to 25 percent of Europe’s population perished in the two years that followed.

Though the severity of the famine had abated a bit by 1317, the cooler, wetter conditions lingered through the decades leading up to the Black Death, and people were left malnourished, with weakened immune systems that could do little to stave off the ravages of Y. pestis.[6]

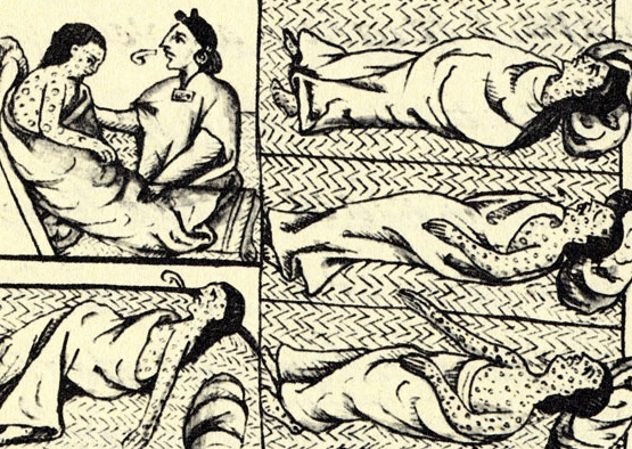

4 People Were Already Weak From Other Diseases

As previously mentioned, the citizens of mid-14th-century Eurasia were already weak and hungry by the time the plague rolled around. Therefore, it would stand to reason that they were often sick in the years leading up to the big show, which, of course, they were. Diseases like typhus, smallpox, and tuberculosis thrived in the confines of their immunodeficient hosts, leaving them weak, weary, and ill-equipped to resist the plague when it came around.

From studying the corpses of plague victims, researchers have determined that many of those who died from it were concurrently ill with the aforementioned diseases and more. They were killed by a terrible cocktail of contagions.[7]

3 Medieval Medicine Was Lacking

One of the foremost accounts of the Black Death was issued to King Philip VI of France by the medical council of Paris. It claimed that the Black Death was caused by an unfortunate alignment of three planets in the heavens, which caused the spreading of a “great pestilence” in the air.[8] People genuinely thought that the black, festering sores and internal bleeding wrought by the plague were brought on by bad air. One can imagine how such a society might have fared in treating a profoundly infectious disease to which it had never been exposed.

Between the iron grip of the Catholic Church on the scientific community, the loss of medical advancements made by prior civilizations such as the Romans and Greeks, and a general inclination toward superstition, medieval medicine was no match for the Black Death.

2 It Had Three Different Forms

As deadly diseases went, the Black Death was something of a Swiss Army knife. It didn’t just go after the blood or the lungs or the lymphatic system—it went after all three, in various forms and stages. Scientists have identified the plague as having three different types: bubonic, the most common and best-known, which caused lymph nodes all over the body to turn into bulbous, black pustules; septicemic, which infected the blood; and pneumonic, which ran the lungs afoul.[9]

All three forms were accompanied by acute fever, and victims often vomited blood. It’s no surprise that a virulence so versatile had such a prodigious kill rate.

1 No Natural Immunity

Ever catch a case of the plague? Smallpox? Tuberculosis? The answer for just about everyone reading is almost certainly no. You probably don’t know anyone who’s been infected, either. You can thank immunization and, in some cases, eradication for that. However, circa 1350, there was no plague vaccine, and the disease was so novel that most people had essentially no natural resistance to it. If people had been exposed to it intermittently over thousands of years, as was the case with afflictions like smallpox, their immune systems might have been better prepared, and the lives of millions could have been spared.

As it stood, no such luxury was afforded, and all but those who avoided infection altogether and a lucky few who bore beneficial mutations that gave them a greater degree of resilience to Y. pestis were doomed to perish. The genetic legacy of the Black Death is evident today, as researchers have discovered that roughly ten percent of Europeans are immune to HIV, a benefit that they believe to be a genetic relic of the mutation that saved their ancestors from one of the closest things to an extinction event that modern man has ever seen.[10]

Trevor Graydon is just your run-of-the-mill grad school dropout trying to make sense of the post-academic world.

Read more festering facts about the Black Death on 10 Facts That Will Change How You View The Black Death and 10 Good Things We Owe To The Black Death.