Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Wild Stories From The Anti-Marijuana Campaign

Recreational marijuana use didn’t become an issue in the United States until after the Mexican Revolution in the 1910s, when immigrants arriving in the US brought with them their intoxicant of choice. “Marijuana” was Mexican slang for a psychoactive variety of the plant Cannabis sativa, of which a non-psychoactive variety known as hemp had been grown in Virginia and other colonies since at least the 17th century.[1]

Prejudice against immigrants played a part in getting marijuana banned in several border states, and such feelings remained in place when the Federal Bureau of Narcotics turned anti-marijuana sentiment into a national movement in the 1930s. Using the yellow press to spread scare stories, the Bureau helped generate support for the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which effectively criminalized the drug.

10 ‘Reefer Makes Darkies Think They’re As Good As White Men!’

One man who stood to gain from conflating drug use with race was Harry J. Anslinger, who had previously worked for the Bureau of Prohibition. When Prohibition came to an end, Anslinger gave up chasing rumrunners to pursue drug dealers as the head of the newly created Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

If Anslinger wanted his new agency to make an impression, then it was in his interest to exaggerate the threat posed by marijuana. Rejecting the botanical term Cannabis sativa in favor of the foreign-sounding colloquial term (which was frequently misspelled “marihuana”), Anslinger targeted his message toward white conservatives.[2]

“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US,” he is quoted as saying, “and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.”

Anslinger’s remarks would cause uproar today, but in the 1930s, the few politicians who spoke out against him couldn’t dent his influence in Washington.

9 Marijuana: Assassin Of Youth

During Harry Anslinger’s first decade as head of the Bureau of Narcotics, several independently made pictures with a marijuana theme were released. Funded and directed by exploitation filmmaker Dwain Esper, Narcotic (1933) and Marihuana (1936) can be dismissed as trash that sought to put rubes in seats by tackling a “forbidden” subject, but Reefer Madness (1936) was funded by a church group and is clearly anti-drug propaganda.

Less well-known but equally propagandist is Assassin Of Youth (1937), named after a magazine article written by Anslinger in the same year. Originally published in The American, the article opens with a young woman jumping to her death from her fifth-floor apartment. “Everyone called it suicide, but actually it was murder. The killer was a narcotic known to America as marijuana and to history as hashish.”[3]

Anslinger then goes on to list several similar cases, most of them taken from the “Gore File,” a compilation of crimes linked (often tenuously) to marijuana use. Several of these stories are referred to in the movie when an undercover reporter is shown The Marijuana Menace, a short film “compiled from articles published in some of our best magazines.”

8 ‘Lives Of Sin, Horror, Corruption And Murder!’

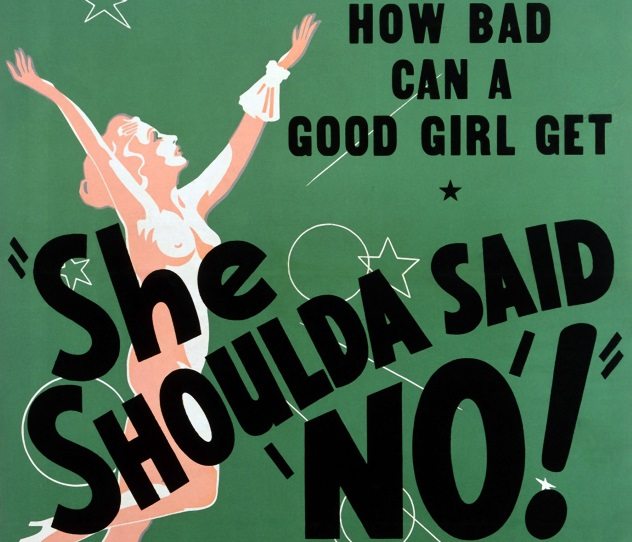

Lila Leeds was a 20-year-old actress with a handful of (mostly uncredited) roles under her belt on September 1, 1948, when she was arrested along with Robert Mitchum. Sentenced to 60 days for marijuana possession, she discovered on leaving jail that nobody wanted to hire her except Kroger Babb, a shady producer who wanted to exploit her newfound notoriety.

Cast as Anne Lester in the 1949 film She Shoulda Said No! (aka Wild Weed and other titles), Leeds plays a young orphan who enters a downward spiral after trying marijuana at a “tea party,” the shame of which forces her brother to commit suicide. Arrested and given a tour of the mental hospitals where marijuana addicts end up, Anne serves 50 days and ends the film clean and ready to cooperate with the police to bring down more dealers.

Publicity for the “semi-documentary” claimed that the film showed how “the use of the weed lead[s] to use of heroin, cocaine, opium . . . and actually leads to lives of sin, corruption, horror and murder!” Just as realistic-sounding was the claim that Leeds would “become one of the leading feminine stars in the motion picture industry.”[4] In fact, She Shoulda Said No! was her last credited screen appearance.

7 Think Of The Children

In Assassin of Youth, Anslinger called for “campaigns of education in every school, so that children will not be deceived by the wiles of the peddlers, but will know of the insanity, the disgrace, the horror which marijuana can bring to its victim.” He was about to get his wish.

Published in 1938, Plain Facts For Young Women On Marijuana, Narcotics, Liquor And Tobacco opens with two young women pleading guilty to their crimes (“these marijuana cigarettes I smoke made it seem right to steal autos and commit hold ups”) and then delivers a stern antidrug lecture. If the intended audience wasn’t alarmed by chapters titled “Maybelle The Doper,” “Marijuana The Assassin,” and “Are Smoking Women Attractive?” then illustrations captioned “Narcotics bind their victims as with chains” and “Marijuana peddlers are a menace to high school students” drive the point home.[5]

The following year saw the publication of Facts First On Narcotics, which begins with a note on pronunciation (“marihuana is pronounced like this: ma-re-hwa’na”) before cautioning students that “it is only a few short steps from a marijuana smoke to the insane asylum.” At the back of the book is a “Things To Do” list that includes such suggestions as “Write a booklet in which you tell why peddlers of drugs, including marijuana, like to have children form the drug habit.”

6 Hallucinations

Claiming to have “spent years investigating and lecturing on marihuana [sic] and other narcotic drugs,” Earle Albert Rowell and his son Robert penned On The Trail Of Marihuana: The Weed Of Madness, a short antidrug book that makes several spurious claims. One of the most amusing is this colorful description of a marijuana addict’s hallucination:

Street lights become orangoutangs [sic] with eyes of fire. Huge slimy snakes crawl through small cracks in the sidewalk, and prehistoric monsters, intent on his destruction, emerge from keyholes, and pursue him down the street. He feels squirrels walking over his back, while he is being pelted by some unseen enemy with lightning bolts.

The Rowells also claimed to have spoken with Dr. James Munch, a “world renowned scientist” who had smoked marijuana and recorded his reaction. “After I had been smoking awhile, I found myself sitting in an ink bottle,” Dr. Munch wrote. “I was in that ink bottle for two hundred years. Then I flew around the world several times.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, Harry Anslinger hired Dr. Munch as the Narcotics Bureau’s expert on marijuana, a position he held until 1962. Testifying before Congress at hearings that preceded the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, Dr. Munch admitted to experimenting on dogs with marijuana.

“The reason we use dogs,” he said, “is because the reaction of dogs to this drug closely resembles the reaction of human beings.”[6]

5 ‘Three Fourths Of The Crimes Of Violence In This Country Today Are Committed By Dope Slaves!’

Written by Annie Laurie (aka Winifred Black) for William Randolph Hearst’s news syndicate, the above quote tells you all you need to know about Hearst’s attitude toward marijuana.

As the owner of vast acreages of timberland, Hearst was determined to prevent hemp from becoming America’s premier paper source. He faced an uphill battle because by the 1930s, the technology existed to not only make hemp papermaking a reality but also make it cheaper and more sustainable than tree-pulp papermaking. The solution: launch a campaign against Cannabis sativa.

It was Hearst who first published Anslinger’s essay “Assassin Of Youth,” although his San Francisco Examiner was attacking marijuana as early as 1923, claiming that the drug “makes a murderer who kills for the love of killing out of the mildest mannered man.” Another factor in his war against the “Mexican drug” was the revolution, which resulted in the loss of some 800,000 acres of Hearst timberland.[7]

4 The Eight Stages Of Addiction

According to On The Trail Of Marihuana: The Weed Of Madness, there are eight stages through which a marijuana addict passes. First is the euphoria, followed by intellectual excitation and illusion regarding space and time. Intense auditory sensibility is then followed by fixation of ideas and overbalancing emotional disturbances.

The penultimate stage is the manifestation of such emotional disturbances, where the addict acts upon their impulses and commits violent irresponsible acts before finally succumbing to terrifying hallucinations.[8]

Authors Robert and Earle Albert Rowell attribute these findings to one Dr. Moreau, “a French scientist of the early nineteenth century who spent many years experimenting with and studying hashish.” However, the only 19th-century scientist Google found was the antagonist of H.G. Wells’s The Island Of Dr. Moreau, published in 1896. Perhaps the authors were mistaken?

3 ‘Marijuana Is A Means To White Slavery!’

This is a another spurious claim made by the Rowells in their book, although to their credit, this time they don’t go as far as inventing sources.

In fact, they don’t give any verifiable details of any kind. While lecturing in “the smaller towns around a large Midwestern city,” they heard “repeated rumors of girls having mysteriously disappeared. It was feared they were in the metropolis, the victims of white slavers.”

The Rowells must have ventured down to “the metropolis” and followed the case carefully because they then encountered frantic parents who “told the Sheriff strange stories of rumors connected with marijuana. One Saturday night, accompanied by a squad of deputies, the sheriff raided the disreputable houses of the city, and found some of the missing girls ‘working’ there. Almost without exception, their stories revealed marijuana as the bait and cause of their downfall.”[9]

2 Jazz Musician = Marijuana Addict

“It had been known for some time that the musician who desired to get the ‘hottest’ effects from his playing often turned to marijuana for aid,” writes Harry Anslinger in “Assassin Of Youth.” “While under the influence of marijuana, he does not realize that he is tapping the keys with a furious speed impossible for one in a normal state of mind.”

To Anslinger’s ears, jazz music was all the proof he needed that those who played it were marijuana addicts (and likely insane). Instructing his agents to follow the likes of Thelonius Monk, Charlie Parker, and Louis Armstrong, he sent the following memo: “We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day. I will let you know what day.”

Giving Washington his assurance that he would not target “the good musicians, but the jazz type,” Anslinger didn’t find the jazz community easy to fracture. He could find no one willing to confess or give up their colleagues. In fact, as soon as one musician was arrested, his friends bailed him out. As the Treasury Department lost patience, Anslinger instead switched his focus to Billie Holiday, an easy target because not only did she use heroin, but her background meant there were unscrupulous characters ready to pass information about her to the authorities.[10]

Anslinger’s pursuit of the singer began in 1939 and lasted until her death in 1959. Even as she lay dying in New York City’s Metropolitan Hospital, narcotics agents handcuffed her to the bed, confiscated her possessions, and restricted visitors. She implored one friend: “They’re going to kill me. They’re going to kill me in there. Don’t let them.”

1 ‘He Killed His Family With An Ax!’

One of the most notorious marijuana stories, repeated in the films Reefer Madness and Assassin Of Youth, concerns a youthful addict who killed his family with an ax.

On October 17, 1933, 19-year-old Victor Licata murdered his parents, sister, and two brothers while they slept. According to Harry Anslinger, the investigating officers found Licata wandering in a daze, unable to remember committing the crime, but when questioned, he admitted to “smoking something youthful friends called muggies.” Licata was subsequently committed to a mental hospital, where he killed another patient before taking his own life.[11]

Though the crime seemed to fit Anslinger’s belief that marijuana eliminated the line between right and wrong, there was a more jarring explanation for the teenager’s behavior. Because Licata’s parents were first cousins, and two other relatives were committed to asylums, the examining psychiatrist concluded that his actions were the result of hereditary insanity.

The conclusion was bolstered by the fact that the police had previously attempted to have Licata committed and that one of his brothers was diagnosed with dementia praecox. Committed to Florida State Mental Hospital, Licata was diagnosed as suffering dementia praecox with homicidal tendencies.

Duane Bradley is the author of the non-fiction books Schlock Treatment and Hillbilly Horror Show. His article on Video Nasties appeared in issue #1 of Red Room Magazine.

Read more about marijuana and other drugs on 10 Stinky Facts About Marijuana and 10 Things We Do And Don’t Know About Synthetic Marijuana.