Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

10 Types Of Evidence That Are Less Airtight Than We Thought

When a serious or violent crime is committed, a part of us wants justice regardless of the cost. We want to feel safe again. We want the victim avenged. We want life to continue as usual.

In times past, criminal investigators didn’t have nearly as much evidence to follow as they do now. They had to make do with witness testimony, fingerprints, and paper trails. But now, we can pull DNA from a microscopic bit of saliva and find a match in a high-tech lab.

As a society, we feel great about this. But the evidence on which we build criminal cases isn’t at all that it seems. Between human error, corruption, and misguided people, the evidence that we use to lock people up for decades of their lives needs a closer inspection. Reform is possible but only when we know what we are up against.

10 Evidence Of Arson

Cameron Todd Willingham was convicted of arson in 1992 after an investigation into the fire that killed his three young daughters. On December 23, 1991, Willingham’s wife, Stacy, left to buy last-minute Christmas presents while he and the girls slept. An hour later, he woke up to his two-year-old crying and a house ablaze. Willingham reports that he attempted to rescue the children, but he was forced out by falling debris and extreme heat.

The conviction became controversial over the years as scientists began to disprove the criteria that investigators used to prove arson at the time. An investigator used to look for certain signs that an accelerant had been used. This meant finding proof that the fire burned too fast or too hot to be natural.

A short list of the signs of arson used prior to 1992 would include narrow burn marks on the walls, crazed glass in the windows, big blisters on wooden surfaces, melted metal, burn marks anywhere on the floor, burn marks on either side of a door, and no easily discernible fire source. If any of these totally normal signs were found in your home after a fire, you would likely be arrested, too.

Scientists have now shown that a fire that burns hot or fast is absolutely normal. An arson investigation today follows the path of the fire through a building to determine if there was foul play.[1]

This information was not available when Willingham was sentenced to death in 1992. But by 2004, when Texas Governor Rick Perry refused to grant a stay of execution for Willingham, it was well established. Willingham was executed shortly afterward, but his case has become a catalyst for those who want to apply new discoveries to old cases.

9 Trace Evidence

Trace evidence refers to small amounts of material left at a crime scene such as fibers, chipped paint, or building materials. Fibers could be anything from a loose string from a shirt to loose carpet bits. When used well, this often becomes circumstantial evidence to bolster other evidence.

One of the more famous cases solved by trace evidence is the Atlanta child murders case. By tracing fibers found on victims to the manufacturer, investigators found that the material was made only during one year in a specific part of Georgia. This allowed them to convict Wayne Williams.

Although this investigation was able to narrow down the fiber’s origins significantly, many are not so lucky. Wayne Williams was arrested in 1981, and fibers were more varied at that time. With modern quality control and mass production, the uniqueness of trace evidence is harder to establish.

But the main issue with trace evidence comes down to human error. Contamination of trace evidence is a huge problem, from the collection in the field to the analysis in the lab. Materials have to be picked up a certain way, stored in the right sort of container, and accounted for all the way to the lab.

Even with all this care taken against contamination, the lab analysis may not be worth all the trouble. From 2016 forward, several inmates have been exonerated and released as FBI testimony based on fiber analysis was refuted again and again.[2]

8 Ballistics

Ballistics is the forensic study of the markings left on the bullet or barrel of a gun that has been discharged. The theory behind it is that gun barrels have unique and specific irregularities inside that cause a reliably identifiable pattern on the bullets discharged by that gun.

Experts study gun barrel diagrams, gun parts, and bullets collected from the gun in question for grooves called striations. They also usually get to take the gun out and shoot some ballistics jelly, which is probably very therapeutic when you investigate violent crime all the time.

There are some problems with the theory behind ballistics. The first is that the parts of firearms, like fibers, are now mass-produced. Their markings are significantly less unique than the fingerprint-like accuracy experts have previously touted in court.

Second, every shot from a gun wears down the barrel, making markings less similar over time. Third, not all irregularities cause striations or cause them every time. Fourth, there isn’t a standardized, validated method for interpreting ballistics information. Marks are compared by eye, and their similarity is down to the expert’s opinion on the matter.

This doesn’t mean that firearm evidence is totally off the table. New research into ballistics focuses on three-dimensional computer renderings made with white light inferometers.

Researchers have been able to digitally compare the markings this way with far more precision than before. Shockingly, this research suggests that only 21 to 38 percent of markings may match when two bullets are fired from the same gun, leaving a lot of previous ballistics testimony in question.[3]

7 Blood Spatter

Not all junk science is used to convict innocent people. The first case of blood spatter evidence exonerated Sam Sheppard, an Ohio doctor accused of killing his wife in 1954.

Paul Leland Kirk, a former Manhattan Project scientist, argued that the blood spatter in the Sheppard home was inconsistent with the prosecution’s case. Just three years later, Kirk was designated an expert in the new forensic science of blood spatter analysis by the Supreme Court of California. In 1966, Sheppard walked free on Kirk’s testimony.

It would all be very impressive if it weren’t based on a ridiculous experiment. Kirk admittedly invented blood spatter analysis by beating a contraption made of wood, sponge rubber, and thin plastic sheeting to learn how different beatings could produce different spatters.

Critics at the time complained that his contraption didn’t seem terribly similar to a human body. Unfortunately, these critics were dismissed as one court after another upheld this form of evidence based on California’s example.[4]

What’s truly shocking is that this form of analysis held up until 2009, when the National Academy of Sciences found forensics in the United States to be severely lacking. It was reported that “the uncertainties associated with bloodstain-pattern analysis are enormous,” a fact that probably should have been apparent in 1957 when Kirk revealed that the basis of his new science was smacking around a wet hunk of wood and rubber.

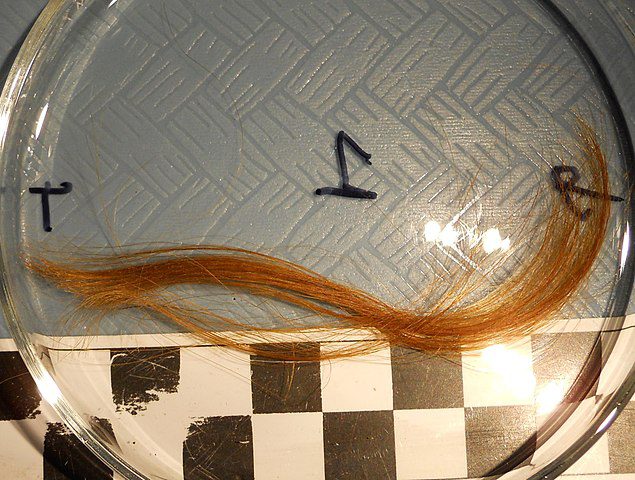

6 Hair Analysis

So far, the problems with these forensic sciences have been down to human error, modernization, and misguided scientists. Hair analysis is different because the FBI has admitted that their forensic unit had been giving flawed testimony for the 20 years prior to 2000.

Of the 28 examiners in this unit, 26 overstated evidence to support the prosecution’s case in 95 percent of cases reviewed. The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the Innocence Project have joined the FBI in the largest post-conviction review in United States history. While only 342 of 1,200 cases have been reviewed so far, 268 of them involve hair analysis.

This sort of hair analysis doesn’t have to do with DNA because the retrieved hairs often lack a follicle and are microscopic. So the method relies on looking at two hairs to determine how similar they appear. This is fine as long as the hair is being used to exclude suspects. If two hairs look totally different, then they generally come from two different people.

However, examiners said that they could also match a hair from a crime scene to a defendant. They said this in court in at least 268 cases. The problem? This implied that the defendant was the only one who could have left the hair. Examiners can’t really rule out other suspects through hair analysis.[5]

In one unfortunate case, the examiners reported that all hairs examined belonged to the defendant. In court, the prosecutor stated that there was a 1-in-10-million chance that the hair sample came from someone other than the defendant, but later DNA testing revealed that at least one of the hairs came from a dog.

5 Bite Marks

Teeth seem fairly reliable as an identifying trait. Dental records have been used to distinguish people since Paul Revere used them to identify soldiers in the American Revolution. So it seems like a bite mark left on a victim would be a good way to identify the perpetrator.

This train of thought likely led investigators to introduce the first bite mark evidence in 1974. An elderly woman in California had been murdered, and an elliptical mark on her nose was identified as a bite from her attacker. The mark was compared to a mold of the teeth of the accused, and this was entered into evidence.

This would seem like good detective work if the mark hadn’t been compared about two months after the woman’s burial. This case created a precedent for later cases to introduce bite mark evidence, which they did without stopping to test its accuracy. In fact, the first real test to put tooth to skin wasn’t carried out until 2007.[6]

Due to the 2007 test, the American Board of Forensic Odontology carried out their own experiments in 2015. This was a full 41 years after the first bite mark evidence was entered in a court of law. Their findings were distressing.

The 39 examiners tested could only agree with 90 percent certainty or more on 8 out of 100 bite marks. Ninety-two bite marks remained questionable. The board later tightened up their criteria for bite mark evidence, but critics say this isn’t enough.

The main argument against bite mark evidence, aside from the fact that no one bothered to check it for 41 years, is that human skin is a very bad surface for transference. Skin is malleable, elastic, and self-healing when living. It is decaying when not and stretched over curves of muscle and fat. Almost anything would be a better surface for transference than an elderly woman’s nose.

4 Fingerprints

Before DNA, fingerprints were the gold standard of evidence. If you had someone’s prints at a crime scene, you knew that you could convict them. This is based on the fact that every single person has a unique set of fingerprints and they show up on surfaces when we touch them.

This is still true, but the issue comes back to transference. Like a bite mark, a fingerprint is often inaccurately transferred. When we touch things, humans tend to use only the top 20 percent of the finger. We also tend to drag the fingertip along surfaces, causing the marks to smudge.

A partial, smudged print from a crime scene will usually be compared to a full set taken from a suspect. Examiners will compare the two prints based on ridge pattern, shape, and location of pores first. If that results in an apparent match, they will move on to matching major structures such as where ridges end, separate, or change direction.

But there isn’t any standardized criteria for how many matching structures examiners need to find before they declare a match. The number ranges from 3 to 16, a huge difference if you’re the one on trial.

Collaborative Testing Services is a company that evaluates fingerprint testing labs by sending sets of pairs of prints for voluntary examination. The prints are complete and clear, which presents far better conditions than field-collected prints. Despite this advantage, the error rate is still 3–20 percent.[7]

Another test with surprising results happened during Byron Mitchell’s armed robbery case in 1999. The defense questioned the accuracy of fingerprint evidence.

To silence this line of inquiry, the FBI sent the crime scene prints and Mitchell’s prints to 53 labs. Only 39 returned results, but 23 percent of them concluded that the prints were not a match. Despite almost one-fourth of the labs returning a negative, the judge dismissed the defense’s concerns and Mitchell was convicted.

3 Eyewitness Testimony

Eyewitness accounts can consist of picking a suspect out of a lineup, describing someone to a sketch artist, or giving evidence in court. This type of evidence relies heavily on the witness’s ability to remember the crime, events surrounding the crime, and the face of the perpetrator. So a witness’s testimony is only as good as his memory.

The issue is that memory isn’t like playing back a recording of what happened. Recalling a memory is actually far more like putting together a puzzle with infinite solutions. Any input from an outsider can influence how that puzzle gets solved. Leading questions from an officer, knowing glances during a lineup, and even questions in court can significantly change a witness’s story.

Even when investigators take care not to lead a witness in his recall, several other factors can upset memory recall. Extreme stress, the presence of a weapon, disguised perpetrators, a racial difference between witness and perpetrator, and a short time to view a lineup all contribute to poor recall. A witness would need to be extremely unflappable to not experience extreme stress during a serious or violent crime.

Concerns over eyewitness testimony were voiced as early as the 1960s, but judges elected to allow eyewitness testimony and leave it up to the jury to decide what they believe. But surveys of jurors have shown that most value eyewitness testimony more highly than more reliable evidence.

This could be because they do not know about the problems of human memory. Many believe that jurors can be educated before a trial to solve this side of the problem. The Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to ending wrongful convictions, has proposed several more solutions.[8]

First, they would like for the identification process to be filmed so that the jury can know the context of the testimony. Second, they suggest that lineups be made more fair by only presenting people who look similar to the initial description and informing the witness that the perpetrator may not be present at all. Finally, the officer administrating the lineup should not know who the suspect is so that he cannot give unintentional or intentional hints.

2 Confessions

Why would someone confess to a crime that he did not commit? It’s a fair question. Even if eyewitness memories are spotty, it seems like a person should know what crimes they’ve committed. But research has shown that false memories are surprisingly easy to implant.

Julia Shaw, a researcher at the University of Bedfordshire, ran an experiment where students were presented with three events, two factual and one invented, from their early adolescence. The invented memories included the student either committing a crime or experiencing a trauma.

When encouraged to remember as much as they could about the false memory, around 70 percent of students recalled the story in vivid detail. According to Shaw, it only takes three hours of friendly interrogation to implant a false memory.[9]

That’s a friendly, three-hour interrogation. Studies show that 84 percent of false confessions happen after more than six hours of questioning. Most police are trained to employ the infamous Reid technique.

Using this method, investigators begin with a non-accusatory, friendly approach. This continues until the investigator decides that he personally thinks the suspect is guilty. Once that happens, questioning becomes accusatory and aggressive. The aim shifts from getting to the truth to getting a confession.

The authority that police have in an interrogation is astounding. They are permitted to keep you, control your access to food and water, imply that a lawyer makes you seem guilty, imply that you will be better off confessing, lie about evidence, and lie about confessions from others. None of this invalidates the confession or is given as evidence to the jury.

If a friendly, three-hour interview can implant false memories, imagine what someone could confess to after 30 hours of this intense interrogation. That’s exactly what five black and Hispanic teenage boys—Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana Jr., and Kharey Wise—experienced in 1989 during the investigation of the New York Central Park jogger case.

The Central Park Five, as they came to be known, all confessed to taking part in the crime of raping a female jogger. But their confessions didn’t match, and their DNA didn’t match any found at the scene. Despite this, they were convicted and spent a collective 41 years in prison before being exonerated by an incarcerated serial rapist’s confession.

1 DNA

DNA is the current gold standard of evidence. In a database of 10 million, there is a one-in-five-million chance of a match. If you hear this in court, it will be presented as a one-in-five-million chance that anyone but the accused left the DNA evidence. But this belies a serious misunderstanding of statistics and what DNA can tell us.

That one-in-five-million statistic refers to the chances that an innocent person’s DNA matches the sample in however many places were tested. What we want to know is the chance of the accused being guilty. DNA can’t tell us that. But we can find out how likely it is that the person matched by DNA is innocent.

In a large database, one particular person’s chance of being matched is extremely low, but the chances that one person (meaning somebody, anybody) will be matched is extremely high. If a chance of a match is one in five million from a database of 10 million, then there’s a high likelihood of turning up at least two matches. If two matches turn up, there is at least a one-in-two chance of each being innocent.

There are ways to make DNA better evidence.

First, more locations on the DNA need to be tested to increase accuracy. Next, it’s suggested that investigators and lawyers treat DNA more like an anonymous tip, especially with more than one match. Finally, it has to be remembered that none of the matches may be related to the crime. Research has shown that some people do not shed as much DNA as others and that a person’s DNA can end up on another even if they have never met.[10]

That happened to David Butler, a retired taxi driver accused of murdering Anne Marie Foy in 2005. Investigators stated that Butler’s DNA was found under Foy’s fingernails, but the DNA found was a complex mix from many people and only made a partial match to Butler.

As noted, the two had never met. However, Butler suffered from flaky skin that caused him to shed tons of DNA. The defense theorized that his DNA could have found its way to Foy on coins transferred by a third party. This would account for the mixed DNA as coins are touched by many people during their exchange. In this case, Butler was lucky. The jury returned a not guilty verdict.

Renee is an Atlanta-based graphic designer who enjoys writing the occasional article.

Read about criminal case mysteries that were solved through forensics on Top 10 Murder Mysteries Finally Solved Using Forensics and 10 Crimes Solved By A Tiny Piece Of Evidence.