Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Little-Known Facts From The Crimean Slave Trade

Slavery is rightfully known as one of the worst evils ever perpetrated against men (and women) by their fellow men. Millions are spent every year on public education about the African slave trade that lasted from the late 16th century until the late 19th century. Although less known, the Arab slave trade in East Africa is also becoming a topic for discussion among a wider audience thanks to the Internet.

Africans were not the only people to ever be enslaved, however. Almost every nation has experienced bondage at some point in their history. Christian slaves from as far away as Russia and Austria could often be found in the slave markets run by the Ottoman Turks. Between the 18th and 19th centuries, the Barbary pirates of North Africa enslaved as many as one million Christians from Southern Europe. During the age of the First Crusade, the Turks themselves were often slave-soldiers called Mamluks.

One of the longest, yet least remembered (at least in the West) slave trades of history centered around the Crimean Khanate, a Muslim state that was a vassal of the Ottoman Turks. Existing from 1449 until 1783, the Crimean Khanate was both a giant repository for slaves (most of whom were Slavic Christians) and one of Europe’s largest slave markets.

The Crimean Tatars and the Turkic Nogai people were responsible for one of the largest slave trades in history. Yet almost nobody outside of Ukraine and Russia has heard of them.

10 A Source Of Great Wealth

Given its location on the Black Sea and its link between the Christian West and Muslim East, Crimea was known for its merchants and mercantile activity. Chief among these traders were the slave traders who bought and sold human cargo from the surrounding Christian states. This trade increased substantially after Crimea became independent of the Mongol Golden Horde. By 1449, Crimea owed its allegiance to the new Ottoman Empire in Anatolia.

A major Crimean Tatar raid into Europe occurred in 1468. This raid reached as far north as modern-day Galicia (a region shared by Ukraine and Poland), and at least one author suggests that frequent Crimean raids into this region led to the creation of a well-known folk saying: “O how much better to lie on one’s bier, than to be a captive on the way to Tatary.”[1]

The amount of wealth these slave raids into Eastern Europe generated is not known at this point. But it is safe to say that given the longevity of the Crimean slave trade, millions, if not billions, were made off the flesh of Slavic and non-Slavic Christians.

9 The Numbers

Few historians agree on the number of slaves who were killed or captured by the Crimean Tatars. However, some numbers have been published in an attempt to give some kind of perspective.

Author Michael Khodarkovsky claims in his book Russia’s Steppe Frontier that 150,000 to 200,000 ethnic Russians were taken into slavery in the first half of the 17th century alone. Correspondence from the time, including the accounts of an Armenian living in Crimea, detail how Tatar raids and Cossack retribution decimated entire villages in the area, killing or selling off most of the male population as a result.

Crimean Muslim author Haci Mehmed Senai wrote that the bad blood between Christians and Muslims generated a culture of rampant violence. Therefore, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648, Senai wrote that Tatar soldiers took joy in killing 10–15 captives per person.

Historian Alan W. Fisher has stated that two million Russians, Ukrainians, and Poles were captured and sold into slavery by Muslims between 1468 and 1694. Furthermore, the Ottoman capital of Istanbul imported as many as 2.5 million slaves from Christian Europe and parts of the Muslim and Christian Caucasus between 1450 and 1700.[2]

8 The Beginning Of The Cossacks

Few soldiers are more feared than the Russian Cossack. Now professional soldiers and members of various paramilitary units, the Cossacks were once nomadic fighters who prized their independence.

Beginning in the 15th century, the term “Cossack” denoted a very specific people—the Turkic and Muslim Tatars of the Dnieper River. However, by the later 15th century, serfs running away from slave-like conditions in Muscovy, Poland, and Lithuania fled to the Cossack lands of what is today Ukraine. Here, Slavic and Turkic men formed roving bands of warriors who made and enforced their own laws.

The growing power of Moscow saw in these unruly Cossacks a chance to provide a military buffer against the powerful Ottoman Empire and their allies. The Polish crown also saw the Cossacks as a potential military ally as well. Both powers granted the Cossacks independence so long as they provided regular military service. Moscow also used the Cossacks as advanced settlers who occupied formerly Muslim regions recently defeated by Russian men-at-arms.[3]

During the age of the Crimean slave trade, the Cossacks were frequently hired to recapture stolen Christian men or at least punish the Tatars for their deeds.

7 Slave Island

According to author Vladimir Shlapentokh, by 1666, the majority of the people on the island of Crimea were not Muslim Tatars but Christian Ukrainians. Invoking the Turkish chronicler Evlia Chelebi, Shlapentokh says that most of these 920,000 Ukrainians were slaves.

The main slave market on Crimea was located at the city of Caffa. Here, Christian slaves were transported overland and by boat to the Ottoman mainland. Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha praised this trade for bringing in 30,000 gold ducats between 1526–27 alone. Some of these slaves became Janissaries, the crack slave troops of the Ottoman army. A majority simply became labor or naval slaves who spent decades, if not the rest of their lives, in bondage.[4]

As late as the early 19th century, Russian travelers and army officers were still finding thousands of Russian slaves being bought and sold at markets in Central Asia, most notably at the Emirate of Bukhara. Some of the older men may have been sent eastward after being captured first near Crimea.

6 The Great Raid Of 1498

Since the 14th century, the Mongol Golden Horde had controlled Ukraine and vast stretches of the Eurasian Steppe. Moscow was a vassal of the Golden Horde, which meant that the only European power that could stand up to the Tatars was the Kingdom of Poland. This political reality meant that Polish and Lithuanian armies battled Tatar horsemen and their allies for supremacy in Eastern Europe for a century or more.

By 1466, Poland expanded by taking control of West and East Prussia, Danzig, Pomerania, and Chelmo. At the time, Poland was under the leadership of King Casimir IV Jagiellon (himself of Lithuanian extraction). Casimir also briefly allied with the Golden Horde to strike against the Russian principality of Novgorod. This alliance proved fleeting as the Golden Horde was a shadow of its former self.[5]

Three decades later, the Crimean Khanate, the new Muslim power in western Eurasia, allied itself with Moldavia, a Christian vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. With approximately 100,000 men, this Tatar-Moldavian army invaded Poland-Lithuania to capture booty and slaves.

The fearsome horsemen met very little resistance initially, capturing the Polish cities of Jaroslaw, Perevorsk, and the garrison town of Przemysl. The Tatars also attacked the key city of Lvov (today’s Lviv, Ukraine), but the Polish defenders managed to fend them off. Before going back to Crimea, the Tatars laid waste to surrounding villages, killing thousands and enslaving many. One author says that 100,000 Polish slaves were captured during the 1498 raid.

5 The Attack On Kiev In 1500

Two years after the Tatar-Moldavian raid on Poland, the Crimean Tatars struck again, this time focusing their wrath on the Ukrainian and Belorussian lands that once belonged to the great Kievan Rus’ civilization. As with the earlier raid, the Muslims were not without their allies.

Prince Ivan III, the Grand Prince of Moscow, asked his Crimean allies to sack the Belorussian cities of Slutsk, Pinsk, Turov, and Minsk. This request was done to keep the Poles off-balance and delay any chance that they might invade Muscovite territory.[6]

Elsewhere, the Tatars attacked Kiev, Chelm, Beltz, and other cities on the Vistula River. The Polish militia, the primary defense force for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was called out. But they failed to apprehend the Tatars before they returned home with booty and thousands of slaves.

The Tatars attacked the Commonwealth again a year later. One historian has noted that the 1500–1501 raids netted the Crimean Muslims 50,000 Slavic Christian slaves.

4 Mehmed Giray’s Assault On Moscow

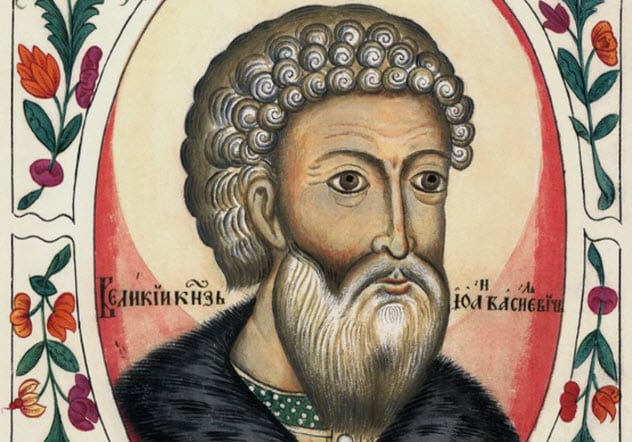

One of the largest Tatar raids on Slavic territory occurred in the summer of 1521. Along with his Kazan allies, Khan Mehmed Giray laid waste to the city of Moscow and captured an untold number of slaves. Khan Giray only retreated from the grand Russian city after he was paid off by Prince Vasily III.

To carry out this impressive raid, Khan Giray led an army of some 100,000 men, including Crimean Tatars, Kazan Turks, Nogais, and some Lithuanians.[7] This force took its time in reaching Moscow. Once there, the Tatars spent weeks pillaging the surrounding areas and capturing men and women for later sale.

By the time that Prince Vasily III assembled an army of several thousand men, the raid was already over. The Tatars and their allies had already achieved their goal—the capture of Christian slaves.

According to the Russian Ostrog Chronicle, Giray’s men carried off 300,000 slaves, while Sigismund von Herberstein, a diplomat from the Holy Roman Empire and an observer to the raid, claimed that 800,000 slaves were taken from Moscow. If true, this means that a majority of the city’s inhabitants were enslaved by the Tatars.

3 Lithuania Turns Back The Tatars

Tatar raids into Christian lands occurred on a regular basis throughout the 16th century. Almost every year, the Crimean Tatars would assemble thousands of men and raid deep into Christian territory. These raids were almost always successful, thus netting the Crimean Muslims thousands of Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, and Lithuanian slaves.

However, despite their battlefield victories against their enemies, the Crimean Tatars were not a unified force in the 1520s. Internal struggles over the position of the khan plus conflicts with their allies meant that Crimea experienced periods of vulnerability.

This changed in 1527 when the Crimean Khanate was once again a unified land. Wasting no time, the Tatars sent a raiding party far north into Lithuania. The ostensible purpose of this raid was to free Sheikh Ahmed, the deposed khan of the Golden Horde. While Sheikh Ahmed was eventually freed from Lithuanian captivity, this was not because of a Crimean victory.

Rather, in January or February 1527, a Lithuanian force of about 7,000 soldiers defeated the Tatars at the Battle of Olshanitsa. After this defeat, the Tatars were harassed by Polish and Ukrainian Cossacks as they retreated south. Following this defeat, the Crimean Khanate pleaded for peace with the Commonwealth and got it.[8]

2 Slaves For The Harem

Male slaves captured in Slavic Europe by the Muslim Tatars usually faced one of two fates: either become Muslim soldiers or work their lives away as labor slaves. Captured females faced other options: either toil as labor slaves or become concubines for the Ottoman sultans. The latter fate was only reserved for the most beautiful.

At Caffa, a full 70 percent of all slaves were shipped south to Istanbul. Once at the Ottoman capital, the human cargo of the Crimean slave ships was inspected by Ottoman officials looking for the prettiest females. Other beautiful women were used as “custom,” or bargaining chips between the various Muslim rulers of Eurasia.

Known by the Turkish term cariye, these female slaves often rose to important positions within the Ottoman court. Many European slave women even became the favored concubines of the Ottoman sultans, such as the Russian woman Hurrem and the Italian woman Safiye.[9]

Some populations, like the Christian Georgians and Muslim Circassians, became known for producing slave women for the Ottomans. Many of these women were encouraged to have as many children as possible, which meant more slaves and more money for the Turks.

Hurrem, originally a Russian war captive, became the wife of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. At court, Hurrem wielded great power and oversaw what has become known as the “Sultanate of Women,” a century-long period in which the women of the Ottoman harem actually pulled the strings of power in Istanbul. Many of these women were European Christians and the mothers of future sultans.

1 Russia Ends The Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Tatars continued to raid Christian lands until the 18th century. In that time, they took thousands of Slavic men and women captive, including 50,000 Poles in 1612, 60,000 Russians in 1646, 100,000 Poles in 1648, and 400,000 citizens of Valynia in 1676. Despite these successful raids, the power of the Crimean Khanate began to slip in the early 17th century. The main reason for this was the rising power of Moscow, then Russia.

In 1552, the Muscovite Prince Ivan IV (aka Ivan the Terrible) captured the important city of Kazan, one of Crimea’s major allies. A Muscovite army of 150,000 men laid siege to Kazan for weeks before the Turkic Muslims finally capitulated.

Following this victory, Ivan declared Kazan a Christian city, began converting the Tatars en masse, and built Russian Orthodox churches all over his new lands. In Moscow, Ivan commemorated his victory by building a splendid Orthodox cathedral—the iconic Saint Basil’s Cathedral.

Although Russia was in the ascendancy, Crimea and the Crimean Khanate were not annexed by Moscow until 1783. The origin of the annexation was the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774.

In that war, Catherine II (aka Catherine the Great) refused the Turkish request to stop interfering in Polish affairs and sent her armies upon the Ottoman vassals of Azov, Bessarabia, and Crimea. Field Marshal P.A. Rumyantsev’s major victories against Ottoman forces in Moldavia and Bulgaria essentially crushed Turkish resistance.[10]

Following the Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca in 1774, the Ottomans agreed to grant Crimea independence and recognize the new Russian borders that stretched all the way to the Southern Buh River. Outright annexation of Crimea would only occur years later after Tatar revolts against Russian rule.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer in Boston.

Read more little-known facts about slavery on 10 Ways Pirates Made Life Better For African Slaves and 10 Black People Who Acquired Wealth During Slavery.