History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Books

Books 10 Famous Writers Who Were Hypocritical

Humans

Humans 10 of the World’s Toughest Puzzles Solved in Record Time

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Scientific Mysteries We Don’t Fully Understand

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Celebrities Who Have Admitted to Alien Encounters

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Books

Books 10 Famous Writers Who Were Hypocritical

Humans

Humans 10 of the World’s Toughest Puzzles Solved in Record Time

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Scientific Mysteries We Don’t Fully Understand

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Celebrities Who Have Admitted to Alien Encounters

10 Fascinating Peeks Into The Daily Lives Of Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs terrorized Earth’s lesser creatures for nearly 200 million years. But many details of their daily lives are lost to history forever—or at least until a reliable time machine is built.

Don’t let that bum you out, though, because scientists are really good at gleaning loads of information from the most seemingly inconsequential remains. From ulcers to foreplay, these scenes of dinosaurian daily life probably won’t be in the next Jurassic Park.

10 They Suffered From Parasites And Ulcers

Fossilized poo nuggets (aka coprolites) reveal surprisingly valuable information.

The ancient feces show that the ruthless reptiles suffered the same affliction as your cat: parasites. Fecal remains from a fossilized Iguanodon graveyard in Belgium were loaded with cyst-causing Entamoeba organisms as well as trematode and nematode worm eggs, parasites that remained mostly unchanged in the intervening 125 million years.[1]

Not even the tyrant king T. rex was immune from tiny invaders. Researchers have on occasion found holes in Tyrannosaurus jaws, which they attribute to protozoans, little single-celled parasites that cause ulcers and lesions in the mouth and throat.

9 Some Land Dinosaurs Swam After Prey

If the carnivores weren’t terrifying enough, there’s evidence that some of them could even swim after their prey.

One such scene is immortalized on a river bottom in Szechuan Province. It’s left behind by a theropod, a three-toed predator a la T. rex but smaller. It swam for about 15 meters (50 ft), scratching a series of claw marks in pursuit of quarry that jumped into the water.

Each mark shows the impression of three parallel claws. And not in a haphazard cat-in-the-bathtub way, but in a “coordinated, left-right, left-right progression.”[2]

So not only were theropods assassins on land, but they could traverse water capably as well. It’s possible that swimming was an innate behavior for some dinos, as it is for dogs.

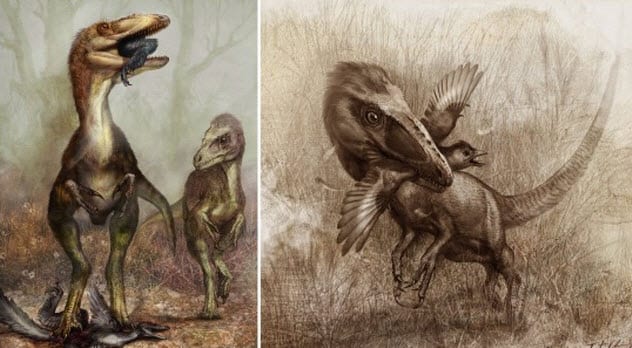

8 Nonflying Birdlike Dinosaurs Ate Flying Birdlike Birds

Researchers found two Sinocalliopteryx so fortuitously preserved that their last meals were still visible.

Sinocalliopteryx was related to Compsognathus, the ankle-biting “Compy” of Jurassic Park and Dino Crisis fame. Only Sinocalliopteryx was larger, up to 2.4 meters (8 ft) long, and covered in a light feathery fuzz. It wasn’t flight-worthy, but it did prey on creatures that were.

In one dinosaur’s stomach, researchers discovered Sinornithosaurus remains from a cat-sized, feathered theropod that could fly short distances. The other Sinocalliopteryx contained two crow-sized primitive flyers called Confuciusornis.[3]

The avian meals may have been scavenged, but they’re in similar states of digestion. So it’s likelier that Sinocalliopteryx was a skilled killer who terrorized early birds of the Cretaceous about 125 million years ago.

7 Sauropods Had Special Claws For Digging Nests

The lumbering long-necked sauropods had a weird arrangement of claws that were unlike other animals. When their feet were flexed, the claws lined up along the front like scrapers.

Sauropod footprints disprove the better grip hypothesis because the claws weren’t “engaged.” Instead, sauropods might have used their scrapers to excavate trench-like nests in which they safeguarded their eggs.

Sauropods were also potentially good dancers. Researchers analyzed some more footprints in Morocco and recreated the dinosaur tracks. They found that the prints occasionally faced sideways and sometimes almost backward.

Before evolution made them ultra-gigantic, the daintier sauropods could rotate their forefeet for better agility depending on walking speed and center of mass.[4]

6 Hadrosaurs Communicated Via Built-In Megaphones

Hadrosaurs are the duck-billed dinosaurs, members of the mostly herbivorous, ornithischian (bird-hipped) clade. Nature’s conveyor belt pumped out hadrosaurs in crested and uncrested varieties, with the lambeosaurs sporting crests on their heads.

It wasn’t just for show. The crests’ tube-filled interior acted as a resonating chamber. It amplified hadrosaur vocalizations, which could have coordinated herding efforts, warned off predators, and/or wooed potential lovers.

Some hadrosaurs, like Edmontosaurus regalis of around 73 million years ago, had a jiggly rooster’s comblike thingy on its noggin. Although it didn’t make noise, it probably signaled reproductive health or age or identified different species for mating purposes.[5]

5 Some Made A Career Out Of Egg Snatching

Oviraptorosaurs (egg thieves) are feathered, beaked, birdlike dinosaurs that include the famous raptors. Most are horrible, but the newest member of the family not so much.

The endearing Gobiraptor minutus prowled Mongolia’s Gobi Desert around 70 million years ago when the landscape was less a desert and more wetland, crisscrossed by rivers and busy with life. Unlike many other theropods, G. minutus secured its niche with a uniquely omnivorous diet.

Its robust beak and strong jaws allowed it to take advantage of all sorts of overlooked food groups. Instead of tearing the flesh from its enemies and friends, it subsisted on small, crunchy dinosaur bar snacks, such as mollusks, seeds, and eggs.[6]

4 Triceratops Horns Weren’t (Primarily) For Fighting

The Triceratops and its horned ceratopsian kin didn’t earn their menacing horns and fancy frills for protection but for sex appeal.

Researchers argue that the trademark horns and ornate armor serve mainly to differentiate between species and to add sex appeal. They seem like implements of war or thermal regulation but could instead be an evolutionarily efficient way to avoid shacking up with the wrong species.[7]

Triceratop-esses didn’t waste their time on genetic scrubs. So a set of mighty frills and horns instantly displayed a male’s hereditary health, as tail feathers do for peacocks.

3 Dinosaurs Engaged In Birdlike Foreplay

Not much is known about dinosaur sex, but in at least one way it resembled bird sex. The revelation comes from a bunch of ancient ruts clawed into a hunk of 100-million-year-old limestone.

The “scrape-like dinosaur tracks” are bathtub-deep, more than 1.8 meters (6 ft) across, and curiously end in a claw mark. These 50 or so ruts, which appeared in pairs, confused researchers.

Then they remembered that modern birds leave similar markings as a prelude to mating. To captivate females, males swagger about and scratch the ground to exhibit their nest-building skill. If these ruts are truly the result of “pseudo-nest-building” foreplay, they’re the first evidence of dinosaurian lovemaking habits.[8]

2 Some Dinosaurs Were Night Owls

Some vertebrates like birds and lizards have a ring of bone around their eyes called the sclerotic ring. Animals that are active during the day have smaller sclerotic rings and smaller pupils that let in less light but allow for greater depth of focus.

In contrast, nocturnal animals feature wide rings and large central apertures relative to eye size. This larger pupil accommodates a higher number of photons for better visibility in low-light conditions.

Based on sclerotic ring remains, the massive, long-necked herbivores were active both day and night, probably foraging during the cooler twilight periods. And raptors (as well as other carnivores) stalked prey by night.

Along with the previously mentioned fact that some dinosaurs could swim, this makes the Mesozoic so much more terrifying.[9]

1 T. rex Was Surprisingly Stealthy

Despite its size and apparent clunkiness, T. rex may have used ninja-like stealth to ambush foes.

Scientists looked at footprints from a variety of dinosaurs and then plugged the feet into computer simulations. The theropod feet proved to be the strangest. They were elongated and twice as long as they were wide.[10]

Sounds clumsy, like trying to run in clown shoes. But unlike other feet, they’re the right proportion for “seismic wave camouflage.” This means that the sound of T. rex footsteps wouldn’t have changed with distance, so unassuming prey animals had no idea how close they were to a thrashing. Less ruthless dinosaurs like herbivores lacked this advantage.

+ Young Dinosaurs Lived Unsupervised

The long-necked, trunk-legged sauropods—history’s largest land animals—easily surpassed 30 meters (100 ft) in length.

A juvenile Diplodocus named Andrew reveals how. Young sauropods were more like ancestral species than adults, which had peg-like teeth fixed in broad snouts. The babies had narrow snouts full of spatula-like teeth. Peg teeth and square snouts are great for chewing on soft ferns, but the young spatulate teeth allowed for consumption of rougher foods.

Researchers say that the juveniles may have lived without parental supervision in age-restricted foraging groups, munching away on tough plants that no one else wanted. As a bonus, isolation helped them to avoid getting trampled by the lumbering adults.[11]

++ Some Dinosaurs Were Adorably Tiny

The name “raptor” inspires dread, but some unique, recently discovered tracks in South Korea reveal an adorable, sparrow-sized raptor that you could hold in the palm of your hand.

The Lilliputian footprints are about 110 million years old and just 1 centimeter (0.4 in) long. Tiny prints like this are rarely found. But here, they’ve been luckily preserved by Cretaceous lake deposits which also safeguarded similarly little tracks left by frogs, birds, and turtles.

These are the smallest dinosaur tracks ever found. They indicate a creature of raptorian persuasion because one claw is lifted, or retracted, while the other two contact the ground. If the newly named Dromaeosauriformipes rarus is indeed a new type of dinosaur and not a chick, it would be the smallest yet.[12]

Ivan writes about neat things for the Internet. You can contact him at [email protected].

For more fascinating dinosaur facts, check out 10 Fascinating New Things We Learned About Dinosaurs In 2017 and Top 10 Recent Dinosaur Revelations.