History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

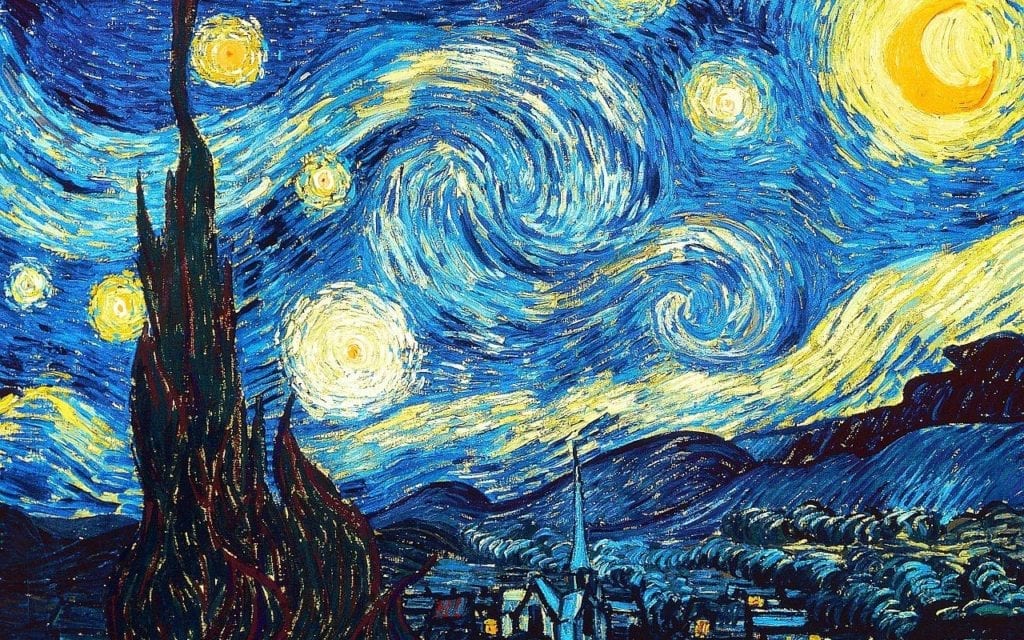

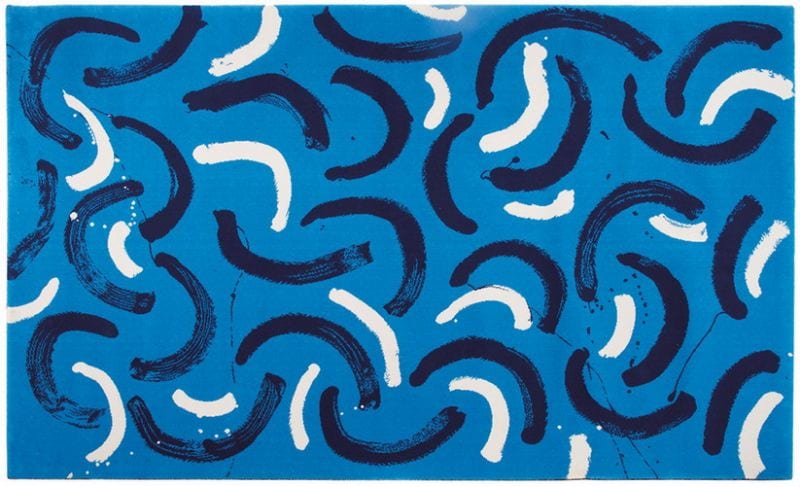

10 Crazy Things That Make Us Love Or Hate Art

When we find ourselves wandering through an art gallery, perusing the many different styles and disciplines on display, we often make snap judgements about what we like and what we don’t like. Those judgements we make, we tell ourselves, are based on our very own tastes. We look, we evaluate and then, confident in our thinking process, we pronounce the painting, drawing or sculpture to be bad, good, great or a masterpiece. It’s a simple, straightforward process. We know art when we see it. Case closed.

Turns out, the process of appreciating art is much more complicated than that. There are numerous strange, subtle forces that make us embrace some art, push other art away or magically transform non-art into art. Here are 10 fascinating examples.

SEE ALSO: 10 Great Easter Eggs Hidden In Works Of Art

10 Being Told

Fact: Simply Being Told That Something Is Art Changes Our Response To It

Recently, a group of Dutch scientists, from Erasmus University in Rotterdam, conducted a series of experiments. A total of 24 student volunteers were hooked up to an EEG—which measures electrical activity in the brain—and asked to evaluate a series of pictures for likability and attractiveness. Half of these pictures were of something nice and half were of something awful. The students were also told that some of the pictures were art and some were pictures of actual events.[1]

What the scientists found was that when the students were told that a picture was a work of art, their emotional response was, “…subdued on a neural level.” In other words, when confronted with what we are told is a work of art, we distance ourselves from it to be able to, as lead researcher Noah Van Dongen puts it, “…appreciate or scrutinize its shapes, colors and composition…”

9 Where It’s Shown

Fact: Where The Art Is Displayed Affects Our Appreciation Of It

A work of art is a work of art. Observed up on a gallery wall or in somebody’s garage, that same painting should be able to be appreciated in the same way in either environment, right?[2]

In 2014, a simple experiment was conducted by a team at the University of Vienna. In that experiment, two groups of volunteers took in an art exhibition—one in a museum and one in a laboratory. A Mobile eye tracking device captured each participant’s viewing time in both places. Afterwards, they were asked to rate each artwork based on, “…liking, interest, understanding, and ambiguity scales.”

The results showed that galleries and museums do matter. Participants in the museum environment viewed each of the individual works of art for a longer time, liked them more and found them more interesting.

Summing up, the team from the University of Vienna concluded that, “…art museums foster an enduring and focused aesthetic experience and demonstrate that context modulates the relation between art experience and viewing behavior.”

8 Hunter-Gatherer Instincts

Fact: The Hunter-Gatherer Era Differentiated What Men And Women Find Aesthetically Pleasing

Next time you disagree with a member of the opposite sex on the aesthetic value of a painting it might just be because, once, long, long ago, men hunted animals and women gathered nuts and berries.[3]

So says Camilo J. Cela-Conde and his colleagues. They hooked up 10 female students and 10 male students to a MEG—which measures the brain’s electrical currents and the magnetic fields it creates—and showed them each hundreds of pictures of artistic paintings, natural objects, landscapes and urban scenes.

They found that when visually evaluating a work of art, men’s brains show stimulation on the right side only, while women’s brains show stimulation on both sides.

From the data they collected, the authors of the study concluded that male and female differences in the appreciation of aesthetic beauty might be tied to the different roles each had during the time of the hunter-gatherer society.

Men hunting needed to “…process a large landscape” and because of this are, “…more comfortable in open configurations and larger art works.” On the contrary, women gathering would, “…seek out nuts and berries and find the same static patch each day” and because of this, “…would be more comfortable and would like small spatial configurations…”

7 Exposure

Fact: We Prefer The Art That We Are Exposed To More Often

Ever dislike a song, the first time you hear it, but grow to like it after listening to it a few more times? That experience has a name.[4]

The “mere-exposure effect” is the experience one has when one begins to like things merely because they are repeatedly exposed to it.

James Cutting, a psychologist at Cornell University, showed his students artistic examples of impressionism for a very brief blip of time—2 seconds. Some of those works of art were considered classics and some were not—though, qualitatively, they were very close. The works of art that were not considered classics were shown 4 times as much.

The results were surprising. The students preferred the non-classics to the classic works of art. A control group still gave the edge to the classics.

6 Electroshock Therapy

Fact: Jolting Your Brain With Electricity Enhances Our Love Of Classic Art

Zaira Cattaneo at the University of Milan Bicocca and her team took 12 people and asked them their opinion of a series of paintings. The twist was that they asked these people before and after they either zapped their brain with a small amount of current or merely pretended to zap them.[5]

The part of the brain that received the jolt, in this experiment, is known as the DLPFC or the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain processes emotions.

Surprisingly, the people who received the zap rated paintings that contained regular everyday moments more highly.

Neurologist Anjan Chatterjee, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, believes that zapping the DLPFC may, “…improve your mood.”

This is why Zaira hopes that, someday, this method may help those suffering from anhedonia—a condition in which people are incapable of experiencing pleasure.

5 Ambiguity

Fact: The More Ambiguous A Work Of Art The More We Like It

We crave clarity. When we shop, we want to see a clearly printed price tag for the item we wish to purchase. When we drive, we want to see clearly printed signs that tell us how fast we can go and when to stop.[6]

When it comes to art, though, we ache for ambiguity.

A study was conducted featuring 29 people who ranged in age from 18-41 and had zero art or art history training. They were shown photos of ambiguous works of art done by Rene Magritte and Hans Bellmer.

The results were fascinating, “The higher the participants assessed the ambiguity of a stimulus, the more they appreciated it.”

What the participants found was that the ambiguous art triggered, “…flashes of understanding as they studied the work, which they found enjoyable even if it didn’t unlock all of its secrets.”

Echoing those comments, researchers also found that, “…subjective solvability of ambiguity was not significantly linked to liking, and was even negatively linked to interest and (emotional involvement).”

4 No Info Please

Fact: Providing Information About A Work Of Art Diminishes Our Appreciation Of It

More information does not lead to more enjoyment—at least when it comes to art.[7]

Psychologist Kenneth Bordens of Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne, recently wrote about a study where 172 undergraduate students—with little to no art smarts—looked at two paintings and two sculptures in one of four styles. Those styles were—Impressionist, Renaissance, Dada and Outsider.

Initially, each student was handed a broad definition of art and a card indicating the style a particular work represented. Then, half of them were handed even more information, including: a definition of that style, a short look at where that style came from and what artists who worked in that style set out to achieve.

Then, using a scale from 1-7, Students had to rate how much they liked each work and how closely it lined up with their personal idea of art.

The study showed that, “Providing contextual information led to participants perceiving examples of the various styles of art as matching less well with their internal standards than when no contextual information was presented,”

Bordens thinks that the extra information provided about some of the works of art may have led to “greater conscious processing” on the part of the participants which may have made them, “more critical.”

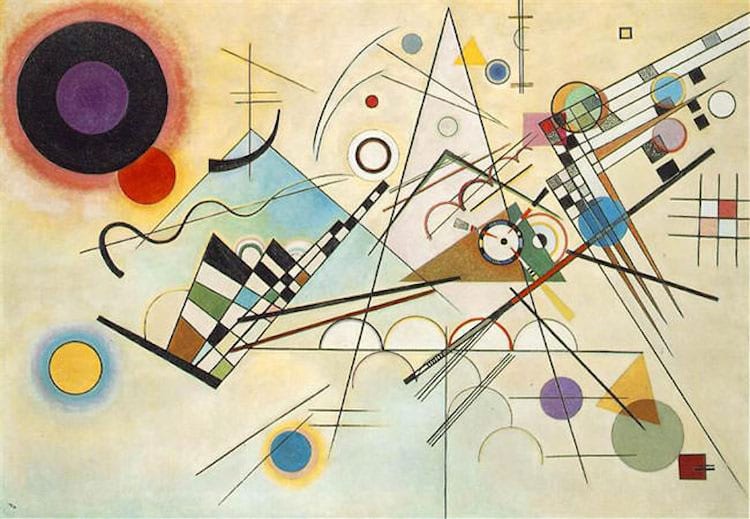

3 Abstraction? Sacré Bleu!

Fact: We Appreciate Abstract Art More In A Foreign Language Context

There is a term in psychology called Psychological Distancing. It refers to the, “…subjective space that we perceive between ourselves and things.”[8]

Elena Stephan, Department of Psychology, Bar-ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel and her colleagues studied psychological distancing and how it related to the appreciation of art.

They argued that a foreign language may create enough of a psychological distance to move an individual, “…away from the pragmatic everyday perception style and enhance appreciation of paintings.”

In the end, they found that abstract art was appreciated more deeply in a foreign language context than in a native language context.

2 Patterns

Fact: Seeing Patterns In A Work Of Art Is Our Sweet Spot

Our brain loves patterns. An ability to recognize patterns is so important that it played a big role in helping our Neanderthal ancestors survive.[9]

Not surprisingly then, recognizing patterns actually gives us a pop of pleasure via our brain’s opioid system.

Jim Davies, a professor at Carelton’s Institute of Cognitive Science, says patterns are crucial in our appreciation of art. “If we don’t see a pattern…we rapidly get bored with it.”

1 Mona Lisa . . . Yawn

Fact: The Mona Lisa Only Became A Masterpiece After It Was Stolen

Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

Whether true or not, absence certainly helped boost the profile and popularity of a certain Leonardo Da Vinci painting.

Though difficult to imagine now, there was a time when interest in the “Mona Lisa” was, “…relatively minimal.” So, what accounts for its now legendary status? The tireless work of art historians? Re-evaluation by art critics of the early 1900s? Da Vinci’s ancestors? No, all it took was a construction worker and a few of his buddies.[10]

Sleeping overnight in the Louvre, Vincenzo and his friends awoke the next morning, Monday August 21, 1911, dressed themselves in workman’s smocks, grabbed the painting and then split via a back stairwell.

The “Mona Lisa” was so uncelebrated that it took 26 hours before someone noticed the painting was missing.

Newspapers around the world announced the theft with big front page headlines. The walls of Paris became crowded with wanted posters. People flocked to police headquarters. Songs were written about it. Through this process, high art became mass art and the people fell in love with Da Vinci’s now universally adored masterpiece.

So, the “Mona Lisa” owes much of its renown and appreciation to an obscure 5′ 3″ Italian construction worker whose brothers called a nut. Strange but true.

For more great lists about art, check out 10 Tragic Cases Of Life Imitating Art and 10 Amazing Artistic Works Lost To History.