Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

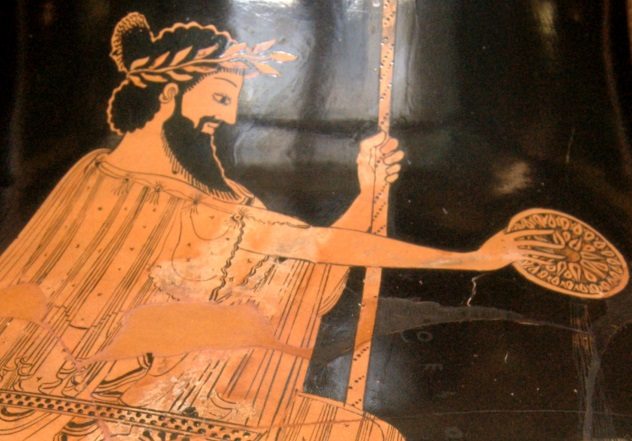

10 Fabulous Tales From Herodotus

Herodotus is known as the Father of History. His book about the wars between the Persians and the Greek city states was a collection of his historia—his inquiries—which is where we get the very word “history” from.

Yet he is also known to some as the Father of Lies. His work contains may diversions. If he found a tale that he thought would interest his audience, no matter how far-fetched, he would include it in his work. Here are ten of the weirdest tales from Herodotus, the historicity of which I leave to you.

10 Gyges Usurps The Throne

Before Herodotus can tell us about King Croesus, he decides we have to learn the strange events of how Croesus’s family came to hold the throne of Lydia. It seems that the former king of Lydia, a man by the name of Candaules, was rather proud of his wife. Nothing wrong in that, you might think. But Candaules had a fetish for showing his queen off to his bodyguards. One member of the guard, Gyges, used to have to listen to the king’s speeches on the topic of his wife’s exquisite beauty.[1]

Perhaps Gyges’s eyes began to glaze over one day as the king subjected him to another eulogy to the queen. Candaules told him, “It appears you don’t believe me when I tell you how lovely my wife is. Well, a man always believes his eyes better than his ears; so do as I tell you—contrive to see her naked.” Gyges tried to get out of spying on the queen, but the king insisted that he hide himself in the queen’s chamber.

Gyges did as he was commanded and saw the queen in all her naked glory. The queen also spotted him. Enraged at her husband’s actions, she gave Gyges a choice: Kill the king or die himself. Gyges did not need much persuading. Candaules was murdered, and Gyges married the queen and took the throne himself.

9 Croesus And The Oracle

From Gyges sprang a dynasty of kings which ended with Croesus on the throne of Lydia. Croesus was so wealthy that the saying “as rich as Croesus” is still used. He was supposedly the first person to mint gold coins. Croesus is important to Herodotus’s history because before the Persians could attack the Greek mainland, they first had to conquer Lydia. Croesus had word that the Persians were coming, but he didn’t know what to do. He did what many in the ancient world did and turned to oracles to get the advice of the gods. But which oracle should he use?

Croesus sent messengers to the most famous oracles in the world and asked them all the same thing: “What is King Croesus doing right now?” All the messengers were to ask the question at the same time, and if any of the oracles got the answer right, then that was the one Croesus would trust. Croesus decided to make the answer difficult to guess—he would be cooking a tortoise and a lamb in a bronze pot.[2] The oracle of of Delphi got it right, so Croesus asked whether he should go to war with Persia. He got the response, “If Croesus goes to war he will destroy a great empire.” Croesus took this to mean the war would go well for him, and he marched his armies out.

Croesus’s forces were destroyed, and he was cast down from his throne. A great empire had been destroyed.

8 Mummification

To the ancient Greeks, the Egyptian civilization seemed impossibly old. Herodotus knew that any facts he could reveal about the Egyptians would be eagerly leaped on by his audience. How could he resist that most Egyptian of arts, mummification?

Herodotus gives us the details of the three forms of mummification the Egyptians use.[3] For the richest people, a complex set of tools and techniques is used to preserve the body. An iron hook is used to pull the brain out through the nose, while a sharp stone is used to cut open the abdomen, and all the internal organs are removed. Sweet-smelling herbs, spices, and perfumes are packed into the cavities before the body is dried in salt to stop it from rotting. Those unable to afford this must make do with having embalming fluids injected into the body. For the poorest people, the intestines were cleared out, and the body was left to lie in salt for 70 days.

One curious fact that Herodotus shares with us about mummification is that the bodies of wealthy ladies were not sent directly to the embalmers. The corpses were allowed to rot for several days to discourage the embalmers from taking “liberties” with them—an early reference to necrophilia.

7 Gold-Digging Ants

When Herodotus describes the Persian Empire, his inquiries go into all aspects of the Persian world, and that includes the fabulous beasts that are supposed to live there. One of the most amazing oddities that the Persians are supposed to possess were gold-digging ants.[4] The ants live in the sands of the deserts near India and are apparently the size of dogs. As the ants dig their burrows, they throw up mounds of sand which are packed with gold. Gold hunters chase the ants on camelback. When they find a mound, they load their camels with bags of the gold-rich sand and ride away as quickly as possible. The ants are swifter than any other animal and would always catch those who seek to plunder their nests if not for the fact that they take their time to form up their troops.

Interestingly, there have been those who do not find this story as absurd as it seems. In the Himalayas, there are marmots, which might have mutated in legend into furry, large ants that dig in areas with high gold concentrations. For generations, locals have gathered up the gold dust that the marmots produce.

6 Polycrates And The Ring

Polycrates was the tyrant of the island of Samos for whom everything seemed to go right. His wars were always successful, his policies were always wise, and even the weather was with him. For us, he might sound like the ideal ally. In the ancient world, however, luck was something that it was possible to have too much of.

The Egyptian pharaoh Amasis wrote to his fellow ruler to warn him about his good luck.[5] Amasis said that the gods would not allow a mortal to have an unending streak of good fortune. One day, there would be a reckoning that would destroy Polycrates and his allies. He suggested that the tyrant should take the thing he valued most in the world and throw it into the sea, so as to break his luck in an orderly way. Polycrates decided to follow this advice. He took a gold and emerald ring from his finger and flung it into the ocean.

Several days later, a fisherman caught an enormous fish. He offered his haul up to Polycrates as a gift fit for a king. While the cooks were cutting up the fish, out fell Polycrates’s ring. This was too much good luck for Amasis, who immediately broke off contact with Polycrates. Polycrates did indeed eventually suffer a terrible comeuppance. He was captured by the Persians, and he may have been impaled and hung up on a cross.

5 Would You Eat Your Parents?

The Greeks loved a good think. Their philosophers tried to discover what things were natural laws (physis) and what were merely social conventions (nomos). Is it a universal law that killing is wrong? People still debate that today. Herodotus gives us an example of a Persian trying a philosophical experiment.

Darius, the Persian king, called all Greeks present at his court together and asked them a startling question: “What would it take for you to eat your fathers’ dead bodies?”[6] The Greeks were taken aback. No amount of money could make them do that; it was evil. The Persian king nodded. Then he talked to some Indians and asked them what it would take to not eat their fathers’ bodies but rather burn them. The Indians were horrified. They thought it was evil not to eat the dead bodies of their fathers.

4 Darius Demands Tribute

Darius the Persian king was not content to sit around asking philosophical problems. The Greek city states had been meddling in the affairs of his domains. He demanded they stop and submit to his authority. To show that they were under his control, all Darius asked of cities was that they give his messengers a token gift of earth and water.[7] Many cities, aware that they were no match for the great empire, did exactly as they were asked. Athens and Sparta, however, did not.

When the king’s messengers reached Athens, they were met with scorn. They were thrown into a pit where criminals were usually tossed. Themistocles, a leading Athenian, wanted to have them put to death for defiling the Greek language with their “barbarian demands.”

The Spartans were even more forthright with the messengers. When they demanded earth and water, the Spartans threw them in a well, saying they would find water there.

3 Cross-Dressing Assassins

Not all the Greeks were so inhospitable. Amyntas, king of the Macedonians, readily gave Darius the earth and water he asked for. He also put on a great feast for his guests. The Persians had fun, but they had one more request. In Persia, they said, it was the custom for married women and concubines to come in and entertain the guests.[8] Amyntas said that was not their custom, but they would do it the Persian way.

The women came in but sat apart from the men, as was their custom. The Persians complained that this was terrible, to see the women and be tempted. Amyntas again complied and let the women sit with the Persians. The Persians began to fondle the women. Alexander (not the Great), son of King Amyntas, was enraged. He begged his father to go to bed so that he could deal with the Persians. Amyntas left. Alexander told the Persians they could sleep with any woman they chose, but it might be better if they waited to sober up first. The Persians agreed to rest.

Alexander gathered all the beardless men he could find and dressed them up as women and gave them daggers. When the Persians began to fondle the “women” that night, the daggers were produced, and all the Persians murdered in their seats.

2 Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae is one of the most famous in European history. The Persian army which invaded Greece was the largest that had ever been seen. It seemed impossible to stop them. At a point where the mountains came down to the sea, a force of 300 Spartan warriors and their allies (numbering in the thousands) blocked the Persians’ path. In the narrows, the Persians could not outflank the tiny number ranged against them.

The Spartans knew they were likely to die, but what they did in preparation surprised the Persians. Instead of being melancholy, the Spartans spent their time tending to their hair.[9] They did also repair a ruined wall to add to their defenses, but one wall and glossy hair did not seem likely to turn the battle.

Xerxes, the Persian king, waited, thinking the Spartans would grow frightened and flee. They did not. Xerxes sent in his overwhelming forces but had to watch as they were repelled again and again. He was at a loss for what to do until a local told the Persians of a path over the mountains that would allow them to take the Spartans in the rear.

The Spartans learned of this move in time to run away. Instead, they stayed and fought to allow their allies to make their escape.

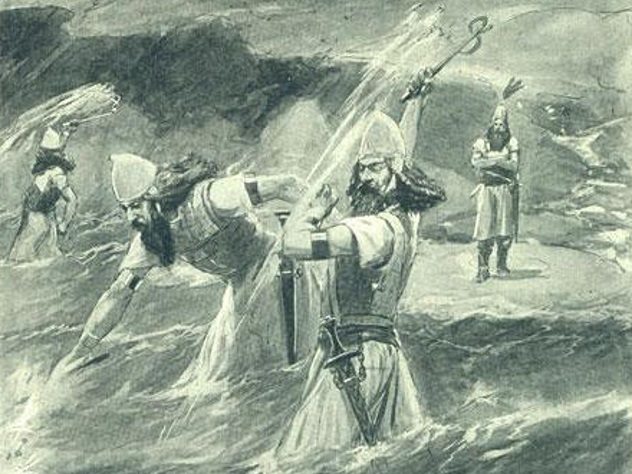

1 Whipping The Sea

Despite commanding the largest empire in the world, Darius’s attempt to conquer Greece failed. He pulled his forces back to Persia. The Persians could not understand their loss. When Darius’s son, Xerxes, ascended to the Persian throne, he decided to finish his father’s conquest.

Xerxes called another huge army for the invasion. Instead of conveying the force by boat, Xerxes had a bridge of boats built across the Hellespont—the narrow gap of water which separates Europe from Asia.[10] The boats were lashed together with ropes of papyrus to allow for the motion of the water. Just as the army approached, a storm came up and scattered the boats. King Xerxes was displeased.

Xerxes commanded that the Hellespont receive 300 strokes of a whip for defying him. He also ordered that fetters be thrown into the water to show that the sea was shackled to his command. To really rub it in to the water, he had iron brands heated red-hot and plunged into the sea. In many ways, the Hellespont got off lightly. The men who built the bridge were beheaded.

Read more about Herodotus on 10 Historical Facts That Herodotus Got Hilariously Wrong and Top 15 Influential Ancient Greeks.