History

History  History

History  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Words That Don’t Mean What You Think They Mean

Space

Space Ten Mind-Bending Ideas About Black Holes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 of the Most Generation Defining Films

Our World

Our World 10 Anomalous Fossil Finds That Stumped Scientists

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Amusing Tales of Lost and Stolen Celebrity Items

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Unexpectedly Funny Slang Terms from the Roaring Twenties

Creepy

Creepy 10 Disturbing Superstitions That Killed

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Top Ten Ways to Become a Zombie

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Book Adaptations You Forgot About

History

History 10 Sobering Submarine Incidents from the 1960s

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Words That Don’t Mean What You Think They Mean

Space

Space Ten Mind-Bending Ideas About Black Holes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 of the Most Generation Defining Films

Our World

Our World 10 Anomalous Fossil Finds That Stumped Scientists

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Amusing Tales of Lost and Stolen Celebrity Items

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Unexpectedly Funny Slang Terms from the Roaring Twenties

Creepy

Creepy 10 Disturbing Superstitions That Killed

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Top Ten Ways to Become a Zombie

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Book Adaptations You Forgot About

10 Ways The History Of Thanksgiving Is Nothing Like You Imagined

The story of Thanksgiving isn’t exactly what you learned in school. There’s a lot more to it than just Pilgrims and Native Americans eating turkey and cranberry sauce. There’s a whole long, winding history that created the holiday Americans celebrate today—and it’s not all what you think.

From the first Thanksgiving feast in the Arctic to the days when kids went door-to-door asking for treats in their Thanksgiving costumes, Thanksgiving’s been through a lot of changes most people never hear about. But without every one of these moments, the Thanksgiving we know today simply wouldn’t exist.

10 The First Thanksgiving Was Held By Arctic Explorers

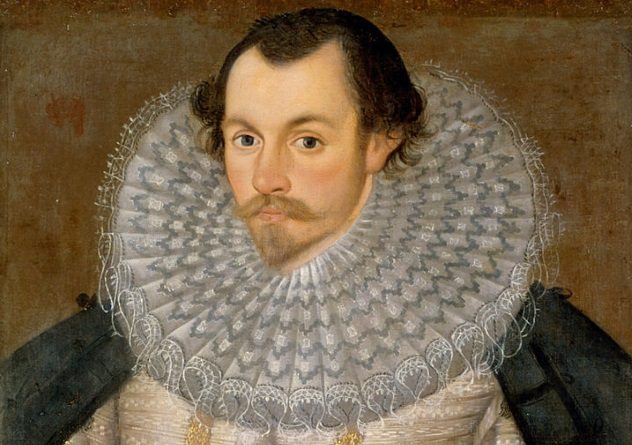

The first Thanksgiving was held in 1578, more than 40 years before the Pilgrims had even arrived at Plymouth—and it was an awful lot colder. It was held among the ice of what would eventually be called Frobisher Bay, and it would become known as the first Canadian Thanksgiving.

When Canadians celebrate Thanksgiving, it has nothing to do with Puritan Pilgrims and Native Americans eating together at Plymouth. They’re commemorating the day the Arctic explorer Martin Frobisher arrived to begin his search for the Northwest Passage. He had already a lost a ship in the ice of the Canadian Arctic, and to keep spirits high, he and his men paused to hold mass, have a meal, and give thanks for the fact that they were still alive.

It was a little bit less glamorous than the holiday we enjoy today. These were Arctic explorers, so they didn’t exactly have turkey. Instead, it’s believed that the first Thanksgiving meal was a scrumptious, one-course repast of salted beef rations and stale crackers.[1]

9 The Pilgrims Ate Lobster, Swan, And Seal

The first Thanksgiving in what would become the United States didn’t happen until 1621, when the Pilgrims at Plymouth, thrilled that they’d had a good harvest, invited their neighbors from the Wampanoag tribe to join them for a feast. They didn’t exactly serve what you’d expect, though.

The Pilgrims put pretty well everything they could find on the table. We don’t know exactly what that entails, but they definitely couldn’t have served pie, stuffing, or cranberry sauce. For the most part, they just ate meat—which probably included turkey, but that would’ve just been a side dish. Instead, most of the table was probably filled with venison and pigeons.

There were some stranger choices, too. Swans are believed to have been caught, killed, cooked, and put on the table. Seafood was abundant. They ate lobster, clams, and they may even have eaten seal.[2] So, if you want a truly traditional Thanksgiving this year, skip the turkey and plop a full swan on your family’s table.

8 The Pilgrims Put The Native Chief’s Head On A Stick

One friendly meal didn’t exactly mean the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag had a lifetime of friendship. After the first Thanksgiving, the Wampanoag chief Massasoit passed away and left his sons, Wamsutta and Metacomet, in charge of the tribe—and things didn’t exactly stay peaceful.

The Pilgrims invited Chief Wamsutta over for a feast—but this time, it wasn’t about being friends. They thought Wamsutta was dangerous, so they slipped some poison into his meal. Shortly after sitting down to eat, Wamsutta keeled over and died.

Metacomet took over next, and again, the Pilgrims tried to invite him over for dinner. Metacomet, though, wasn’t about to fall for that one. Instead, he waged war, attacking more than half of the English settlements in America and killing 600 people.

In the end, though, the Wampanoag lost. The Pilgrims managed to run Metacomet down. They dismembered his body and put his head on a pole over Plymouth.[3] It stayed there for 25 years, looking down on the spot where his father and the Pilgrims had celebrated the first Thanksgiving.

7 Children Went Door-To-Door Asking For Treats

During the 19th century, a brand new Thanksgiving tradition began: “Ragamuffin Day.” Children started dressing up, going door-to-door, and asking for treats. Thanksgiving, for a while, was an awful lot like Halloween—except that it was an awful lot crueler.

The Thanksgiving Ragamuffin tradition started in Massachusetts when a group of poor children who were starving to death went to their neighbors’ doors begging for scraps of food, asking, “Something for Thanksgiving?”

The rich kids saw the plight of the less fortunate, and they thought it was hilarious. As a cruel joke, they started imitating them. Every Thanksgiving, the wealthier kids started putting on tattered clothes and going door-to-door pretending to be beggars. In return, people would hand out pennies, apples, or pieces of candy.[4]

Going door-to-door was a Thanksgiving tradition for decades. It didn’t end until the Great Depression hit, and suddenly nobody had any pennies to share. Pretending to a beggar wasn’t as funny as it once had been, and the fad died out.

6 The Thanksgiving Tradition Of Burning Small Children

Ragamuffin Day, in New York, was even crueler. It evolved into its own unique festival in the Big Apple, with its own distinct traditions. The oddest one has to be the “red pennies”—the unique New York tradition of spending Thanksgiving Day hurting children.

A “red penny” was a penny that had been heated up in the stove until it was too hot to touch. When the kids in the neighborhood hit the streets in their costumes and started going door-to-door, some New Yorkers would go to their windows and throw these scalding hot coins out onto the streets. Then they’d howl in laughter as they watched small children burn themselves.

“I remember the fun we had,” one New Yorker told a reporter after the fad of Ragamuffin Day had died out. “When we kids picked ‘em up we got our fingers burned. I remember how my fingers got blistered.” Then, nostalgic for the lost days of being tricked into injuring himself, he sighed and said, “They don’t have any real fun like that anymore.”[5]

5 We Wouldn’t Have Thanksgiving Without ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’

Thanksgiving would never have become a federal holiday if it wasn’t for one woman: Sarah Josepha Hale. Or, as she’s better known, the woman who wrote “Mary Had A Little Lamb.”

Hale did more than just write a children’s song—she also waged an absurdly long and hard-fought battle to make Thanksgiving into a major US holiday. Thanksgiving, Hale believed, had a “deep moral influence” that taught families the value of coming together, or as she called it, “in-gathering.”[6] And she wouldn’t rest until every family in America was doing it.

Her first novel, Northwood, had a chapter-long description of Thanksgiving and how great it is, worked in just to push her favorite holiday on the public. After it came out, she founded her own magazine for women and filled it with articles on why everyone should celebrate Thanksgiving. And in her spare time, she wrote letters to senators begging them to make it a federal holiday.

She dedicated more than 30 years of her life to making Thanksgiving a holiday—and it worked. Slowly, more and more people started celebrating it. By 1854, 30 states were observing Thanksgiving, mainly because of her.

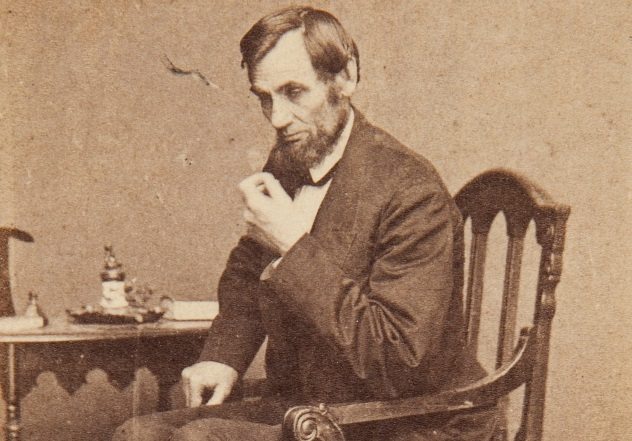

4 Thanksgiving Became A Holiday To End The Civil War

One of the people Sarah Josepha Hale wrote was President Abraham Lincoln. She’d been worried about the Civil War, she explained, and felt that the US needed to “put aside sectional feelings” and rally around a common cause that everyone could agree upon. And, since Hale was a bit one-note, she figured the perfect cause was Thanksgiving.

Lincoln wasn’t the first president she’d written, but he was the first to listen to her. He took to her immediately. A mere five days after Hale wrote her letter, Thanksgiving was declared a federal holiday.[7]

Lincoln issued a declaration inviting people “in every part of the United States” to come together and give thanks for the good in the country, partly as a way to improve morale of Union troops and partly to try to rebuild a sense of national identity. He filled the holiday with pictures of Pilgrims coming together, trying to create an idea of united America.

The holiday caught on, in the end, both in the North and the South. But during the war, things weren’t exactly equal. While the Northerners carved up turkeys and enjoyed the feast, people in the South sat down for “starvation parties”—where people would do everything they enjoyed in peacetime except for the one thing they couldn’t afford: eat food.

3 Lincoln Wanted It To Be A Day Of Humiliation And Fasting

Turkey and gratitude had nothing to do with Lincoln’s original vision for Thanksgiving. In 1861, before he read Hale’s letter, he tried making his own brand-new festival to bring the country together. But he didn’t want people to give thanks and eat food. He wanted it to be—in his own words—a day of “public humiliation, prayer and fasting.”[8]

The day would be packed with festivities. Lincoln’s holiday was to start with people acknowledging the “Supreme Government of God” and bowing “in humble submission to his chastisements.” Then they were to publicly confess and deplore their sins and transgressions and beg for forgiveness.

Lincoln’s hope was that, if America repented of its sins, God would bring an end to the Civil War. His day of self-hatred, starvation, and prayer, though, didn’t exactly catch on quite the same way Thanksgiving did.

2 Lincoln’s Son Begged For The First Turkey’s Life

The tradition of having the president pardon a turkey on Thanksgiving started on the very first year of the holiday—and it all came out of the sympathy of a ten-year-old boy.

The Lincolns had a live turkey sent to the White House for their dinner in 1863. Lincoln’s young son Tad got the chance to see the animal that would be soon be killed, fried up, and placed on his dinner table, and when he realized what was going to happen, he became terrified. He begged his father not to kill the turkey, telling him that it had “as good a right to live as anybody else.” The president was touched. He agreed, and the White House brought in a new pet turkey.

The tradition didn’t exactly catch on right away, though. The presidents who followed didn’t really share Lincoln’s sentimentality. They followed his tradition of having live turkeys sent to White House and sometimes posed for pictures with them—but they went ahead and killed and ate them anyway.

It took until 1963 before JFK became the first president since Lincoln to let the turkey live—exactly 100 years after Tad Lincoln had saved the White House’s first Thanksgiving turkey.[9] JFK was assassinated three days later.

1 FDR Changed The Date To Increase Holiday Profits

Thanksgiving went through one more change in 1939, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt changed the date—purely so that people would spend more money on Christmas presents.

President Roosevelt realized that people didn’t start shopping for Christmas presents until Thanksgiving was over. He figured that if Thanksgiving was a week earlier, people would start shopping earlier and end up spending more money. And so he moved Thanksgiving from the last Thursday in November to the second-last Thursday, purely to boost the economy.

People were furious. They started calling his date “Franksgiving,” and some states refused to recognize it. Alf Landon, who had run against FDR in 1936, even declared that changing the date of Thanksgiving made Roosevelt “a Hitler.”[10]

It actually worked, though—people did spend more money, and the economy did improve. In the end, Roosevelt got everyone to calm down by switching the date again, now declaring that Thanksgiving would be on the “fourth Thursday in November” but “never on the month’s last two days,” which was confusing enough that nobody bothered to argue about it.

Read more about Thanksgiving on 10 Thanksgiving Words With Bizarre Origins and Top 5 Worst Thanksgivings.