Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Simple Things That Aren’t As Old As You Think

Modern life is full of simple conveniences. It’s easy to forget that we had to cope without them not too long ago. From our plates to our chairs, some of the simplest things we use daily owe their existence to the explosion of leisure and luxury that followed World War II.

Even simple tools like forks, which we assume must have been around forever, were only introduced to Western and Northern Europe in the last couple of centuries. In this list, we’ve rounded up 10 of the most surprising simple things that are not as old as you think.

10 Sofas

Like many fashionable things, sofas and couches first appeared in the royal French court. Portraits from the late 1600s show noble French women lying down on sofas.

German dignitaries who visited the French court complained that it didn’t look like a royal court anymore because everyone was sitting or lying around. These sofas were more designed for lying than for sitting on, however, and they bore little resemblance to the sofas we sit on today.

The first example of something we might recognize as a sofa now was the chesterfield, a design which can still be found today. It was created in the 1700s by Lord Chesterfield, who wanted it to be a place where the elite could sit and retain their dignity. The chesterfield was a hit with the British upper classes and quickly spread to many mansions and manor houses across the country.[1]

The average man or woman, however, still didn’t have a sofa or couch in their home. The living room, or lounge, became more common during the Victorian era as the homes of the lower classes became more luxurious.

But they were still usually places of family activity. In short, most Victorians didn’t see much of a need to buy a large, expensive seat when they could invest in books, drawing equipment, or musical instruments.

The rise of the couch largely coincided with the explosive growth of radio and television, both of which gave people more of a reason to sit idly in their living rooms. Meanwhile, new furniture trends meant that they became simpler and less expensive, making them more affordable for the modern family.

By the end of World War II, most homes in the West were being built around a central living room dominated by a couch and a television.

9 Highways

These days, most of us think nothing of jumping on the highway to travel long distances. But the US is vast, and journeying from one state to another without the assistance of the highway system is almost unimaginable. Until surprisingly recently, however, if you wanted to travel across the United States, you had to put up with some awful local roads.

The plan to build the highway system was only put in place in 1956. The Federal Aid Highway Act set out a plan for over 64,000 kilometers (40,000 mi) of high-capacity interstate roads that would be able to accommodate large numbers of automobiles at once.

The goal was to eliminate unsafe roads and inefficient routes and to ensure safe and fast travel across the country. One of President Eisenhower’s main concerns, however, was that population centers across the US should be made easier to evacuate in the event of a nuclear attack.

During World War II, Eisenhower had been present in Germany where the Nazi Party had organized the construction of a wide-ranging highway system in the 1930s. He returned to the US determined to bring the same thing to America.

However, the construction of such an ambitious project required sacrifices: Many old towns were cut in half by the new roads, and hundreds of buildings, including people’s homes, had to be demolished to make way for these highways.[2]

Protesters opposed the construction in many places and delayed the process. Meanwhile, other unforeseen issues blocked progress in other areas. The Interstate Highway System was finally declared complete in 1992.

8 Dinner Plates

We’re more than used to eating our dinners from ceramic plates today, but until recently, only the wealthiest in society were able to afford this luxury. Just a few hundred years ago, the idea of a ceramic dinner plate was entirely foreign to the West.

In medieval times, most people ate their food out of a wooden bowl. Plates weren’t commonly used because the vast majority of meals (or at least, those not eaten by the wealthy) came in the form of soups, stews, and porridge.

Wooden bowls were simple, cheap, and practical. When the average man or woman needed something more like a plate, they used a trencher—halfway between a plate and a dinner tray. Often, these trenchers were made from old, stale bread that had gone hard. The trencher could then be eaten after the meal or, if you were richer, handed out to the poor as alms.

The upper classes ate their meals from plates, platters, and bowls of pewter. Unfortunately for them, pewter often contained lead, so they tended to get lead poisoning over time. Apart from that, the crockery of the upper classes looked fairly similar to the stuff we use today.

In the 1600s and 1700s, the European nobility developed an obsession with all things Chinese and Japanese. This affected everything from decor to furniture to painting styles, but it was especially felt in the dining room.[3]

The wealthy loved to show off their fine china—their ceramic and porcelain teacups and plates which they’d imported from the East. While owning a full set of ceramics was the dream, it was also very expensive, so very few could afford it.

During the Victorian age, the ceramics industry was industrialized. Places like Stoke-On-Trent in the United Kingdom began making ceramic crockery for a fraction of the normal price. By the 1900s, nearly every person in the UK and the US was eating their meals from ceramic plates.

7 Novels

Literature and drama have existed for thousands of years. Even if we can’t name an ancient Greek tragedy off the top of our heads, most of us have heard of them, and many of us had to read Shakespeare at school. Nearly all ancient entertainment had one thing in common, though. It was designed to be performed and enjoyed communally—on a stage or at an event rather than alone in private.

Back in Shakespeare’s day, even the most dedicated of his fans would never have read the plays on paper. Much like how we enjoy films today, most entertainment then required no reading.

The birth of the novel largely coincided with the rise of literacy among the common people. However, for most of history, books were largely nonfiction.

They served as references or guides for a scholarly or wealthy elite who could afford to learn the skills to read them and had the money to buy them. But as everyone in society became capable of reading, a new market emerged for people willing to read literature by themselves.

The first novels walked a fine line between fiction and nonfiction. Most of them posed as the biographies of real people with sensational stories, such as Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. The novel as we know it today emerged in the early 1800s. One of the first novels to gain widespread popularity was Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, published in 1812.[4]

6 Picnics

Picnics are the kind of thing we end up doing with our parents and other elder family members. They’re a simple, quiet, nice, slow-paced way to spend our afternoon. They have a quaint, old-world charm to them, as though they belong in a more peaceful, traditional age than the one in which we live.

If someone pointed this out to a Victorian, however, he’d probably have scratched his head and looked at the person funny. This is because the picnic was usually an indoor party. It was a tradition brought to Britain (and therefore America) in the late 1700s by exiled French nobles who’d been pushed out by the French Revolution.

Many of them were used to better lifestyles than they could now afford, so they began jointly hosting parties to make them cheaper. One person would provide the venue, and all the guests were expected to bring some food (and a lot of alcohol) to contribute to the buffet. For most of the Victorian era, the picnic meant a drunken indoor party, usually featuring amateur plays and partying deep into the night.

For reasons that are unclear, the picnic was adapted by the English middle classes in the early 1800s. The country was right in the middle of the Romantic movement, which glorified nature. So, many of them took their parties outside to be closer to the wild world.

Both indoor and outdoor picnics existed side by side until the early 1900s, by which time the outdoor picnic had prevailed. It wasn’t for a few more decades, however, that the alcohol and partying was replaced by the sandwich and wicker basket.[5]

5 Supermarkets

Many of us dread having to make the weekly trip to the supermarket. Within recent memory, however, doing the weekly shopping meant going to more than one place: bread from the bakery, meat from the butcher’s, fruit and vegetables from the greengrocer’s, and cereals, canned goods, and the like from the grocer’s. Nearly all these stores were run by individuals or families and had their own suppliers, prices, and customs.

Chain stores first appeared in the US in the 1920s, but they still more-or-less followed this system. It wasn’t until 1930 that the first supermarket appeared, but it took a long time for the world to adapt to them.[6]

Especially in Britain, where the first supermarket opened in 1948, people struggled with the concept of the supermarket, feeling rude for taking items off the shelves themselves and being stunned by the wide selection of items available. Through the whole of World War II, not a single British family bought their food in a supermarket.

Old habits die hard. Even as late as 1950, only 35 percent of America’s food was bought in supermarkets.

The retail world we know today finally came about in the 1960s, which saw the rise of gigantic, stylish supermarkets which were finely tailored behind the scenes to draw in and keep customers. Meanwhile, shopping centers and the like were collecting together smaller, more specialized stores for convenience.

4 Ovens

Ovens are one of the oldest tools used for cooking food. Thousands of years ago, they were basic constructions. Made from clay or dirt, they could be as simple as a hole in the ground with a fire.

But even through the medieval period and beyond, most households didn’t have an oven. Instead, they bought their cooked foods directly from the baker or paid him a small amount to use his oven themselves. This was because ovens were large and difficult to move and manage, especially within the relatively meager home of the average medieval family.

The first cast-iron ovens were made in fairly high quantities in the 1700s, and innovation during the Victorian age made them smaller, more advanced, and cheaper. It wasn’t until the 1830s that the first compact iron ovens were commercially successful, but even then most people still did most of their cooking over a hearth.[7]

The modern product, with an internal oven and a cooktop for pots and pans, was only found in most houses in the West as late as the 1920s. By that time, electric ovens had already begun to compete with the gas variety.

3 Backyards

Though the backyard may conjure up unwelcome thoughts of mowing the lawn or weeding the flower patch, our backyards today are indisputably places of entertainment and enjoyment. Whether we use them to host barbeques or sit on the patio, there’s no disputing that our yards are like our own private parks today.

Until recently, though, the yards behind our homes were places of work, not leisure. Before indoor plumbing and bathrooms, most homes had an outhouse at the bottom of the yard.

Before refrigeration, the families whose homes didn’t have cold, dry cellars dug a root cellar in the yard to store fresh food. A lot of the time, this fresh food was homegrown because much of the yard was given over to garden space for growing root vegetables like carrots, potatoes, and turnips.[8]

Even in urban areas, the yard often supplemented the economy of the household. It might be used for woodwork or other artisanal trades that would otherwise have required the renting out of a workshop. It could also be used to keep animals such as chickens or dogs, something which is still relatively common across America.

Using the yard as a practical place came to an end in the postwar economic boom years of the 1950s and ’60s. Advertisements and media began to portray the home as a place of rest from work. The stereotypical family unit was dominated by a man who drove to work every day and a woman who stayed at home and looked after the kids. Society changed, and the yard turned into a place of luxury rather than work.

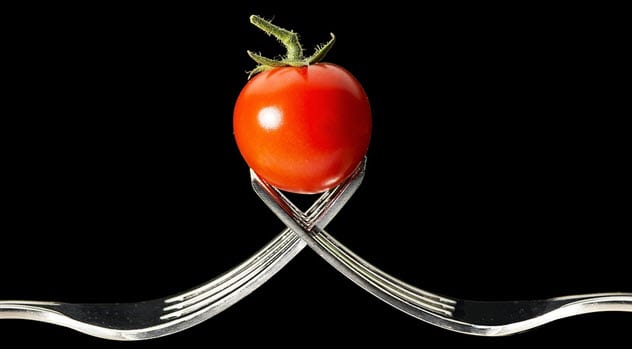

2 Forks

We’ve been using forks in the West for hundreds of years . . . but they were a farming and gardening tool. The idea of using a small fork for eating food was a novelty and would have earned some loud laughs until relatively recently in history.

From the medieval period and beyond, most people used a knife to eat their food. This was the same knife they carried around on their belt and used for their other daily chores.

If you were a wealthy person, you had special spoons (often silver) for feasting, but these were handed out and collected again at mealtimes to ensure that none were stolen. Even in these situations, most guests brought their own knives to the table and forks were unheard of.

When a second implement was required to handle the food, most—including the richest—just used their hands. This was partly why they washed their hands before and after every meal.

At first, forks were distrusted and ridiculed. Medieval religious writers used them as an example of unnecessary vanity and excess, suggesting that the desire not to touch the food was an example of pride. Others just thought they were ridiculous, difficult to use, and rather pointless. This may have been true as the few medieval forks were usually two-pronged.[9]

The fork reached France in the late 1500s when Catherine de Medici brought the custom to the royal court and introduced it to the nobility. It remained a tool of the elite for a long time, eventually entering common use in France in the 1750s and in Britain and beyond in the 1800s.

Even then, there were those who shunned the fork and its strange ways. As late as 1897, some British sailors refused to eat with forks because they considered the implements unmanly.

1 Beds

These days, there are as many ways to customize a bed as there are people to sleep in one. We can select from thousands of different mattress materials, sizes and styles, different duvet thicknesses, and an uncountable number of duvet colors and patterns. No two beds have to look the same.

But the bed, as simple as it seems, hasn’t been around all that long. Indeed, we’re still tweaking the technologies of memory foam and the like to this day. But go back in time—say, to the medieval period—and beds become almost unrecognizable.

If you were moderately wealthy, your family would own one very large bed. This bed, surrounded by posts and curtains, was usually big enough to host four or five people and could be used by the whole family at once. The very richest had beds for the parents and separate ones for the children. The average person, though, made their bed on the floor with fresh rushes and perhaps a blanket.

Life in medieval times was much more communal than it is today. Most people thought nothing of sharing sleeping space with those around them despite the obvious privacy concerns.[10]

In the early medieval period, even the concept of the bedroom as its own separate room was rare and somewhat alien. The idea of separate bedrooms developed during the Renaissance, but it didn’t become entrenched in all classes of society until the 1700s. Even then, it was common for up to six siblings to share a single bedroom, if not a single bed, without anyone batting an eyelid.

Beds themselves continued to develop. The idea of corner posts fell out of fashion, and the first spring mattress was designed in the middle of the Victorian era. It was crude and squeaky, however, and innerspring mattresses didn’t become common until the 1950s. By that time, the minimalist bed frames of today had become fashionable.

Read more misconceptions about the things around us on 10 Simple Things That Are Deceptively Complex and 10 New Things We Think Are Old.