Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Remains Of Extinct Species With Rare New Insights

The past few years saw an unprecedented slew of remarkable fossils. It is not always the biggest dinosaurs that are the most valuable to science. More important are the fragments that reveal behavior, extinct diets, missing ancestors, and the answers to tough puzzles.

New finds can also introduce intriguing mysteries about unknown human species and animals. They can be dramatic, too, showing for the first time the creatures that died minutes after the dinosaur-killing asteroid struck Earth.

10 Comb Jelly Ancestor

Some researchers love their jellies. The predatory and gelatinous kind, not the wobbly dessert. Recently, a scientist from the United Kingdom visited colleagues in China. When he was shown a particular fossil, he got very excited over the creature’s tentacles. The fossil, later named Daihua sanqiong, sprouted 18 whips around its mouth.

Each tentacle had robust ciliary hairs, something only found on comb jellies. The latter is alive today. This bizarre creature uses “combs” of cilia to travel through seawater. The comb jelly was a bit of an orphan. Nobody can follow its evolutionary progress on the tree of life.

However, the 518-million-year-old fossil shared enough characteristics with comb jellies and other ancient creatures that researchers could tentatively build the entire early lineage of comb jellies. It even gave the Oliver Twist of the jelly world a few likely cousins—corals and anemones.[1]

9 Bandicoots Were Nimble

Pig-footed bandicoots went extinct in the 1950s. Like most marsupials, they were delightfully different in their own way. These bandicoots looked like they had been assembled from pieces taken from a deer, a kangaroo, and an opossum. Weighing about the same as a basketball, bandicoots were among the tiniest grazers that ever lived.

As there are no living animals, researchers turned to the aboriginal community for insights about the creature’s behavior. Done in the 1980s, the interviews revealed something surprising. The ungainly animal could gallop quite fast.

What made this fact so unexpected was the structure of the bandicoot’s feet. Each front leg had two functional toes, and bizarrely, the hind legs had one each. This arrangement appeared unstable. But according to witnesses, the herbivores zoomed into the distance like the Road Runner when they were startled.

Interestingly, in 2019, a DNA analysis was performed on the last remaining 29 skeletons in museums. It revealed that what researchers thought was one species, Chaeropus ecaudatus, was in fact two. The new species was called Chaeropus yirratji to honor a local aboriginal name for the animal.[2]

8 Worm City

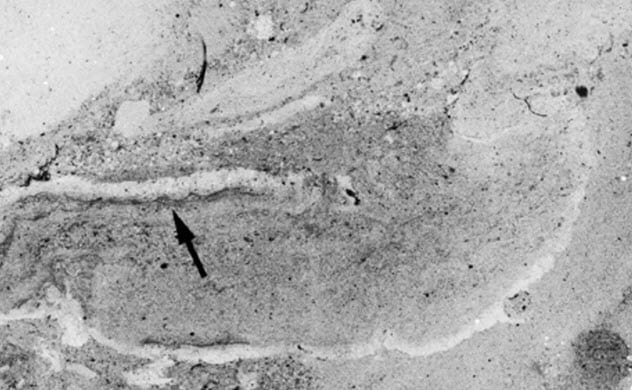

In 2018, rocks were analyzed from Canada’s Mackenzie Mountains. Nobody had worms on the brain while preparing the rocks for another study. However, during the grinding and sawing, unusual colorations prompted a look—and it changed a big belief.

To find out what caused the unfamiliar shades, samples were scanned and digitally enhanced. Almost instantly, a crowding network of tunnels appeared. Previously invisible, the tunnels were made by a thriving community of worms. This may sound torture-level normal, but it showed life where none was expected.

The rocks dated back 500 million years when the region was a seafloor. Most experts agreed that it was a dead zone due to no oxygen. But some rocks were so tunneled that they resembled the highways of a busy city. This proved that the dead zone harbored more life—and definitely more oxygen—than anyone had guessed.[3]

7 Step Closer To Ancestor X

Ancestor X is the mysterious focus of a scientific argument. It involves the early evolutionary tree of vertebrates, animals that include humans. Ancestor X is not a primate but a fish. This aquatic grandparent, so to speak, was identified in absentia when researchers had a look at some the oldest vertebrates alive today.

Most felt that the boneless hagfish and lampreys belonged at the bottom of the tree. This suggested that X looked similar to the two eellike species. Fossil finds supported this theory. DNA tests did not.

Genetic analysis suggested that lampreys and hagfish had an ancestor that branched off much earlier. The debate swung in the DNA’s favor when a fossil was discovered in Lebanon in 2011. It was an early type of hagfish that was around 100 million years old.

Considering that hagfish have no bones, finding one was “like finding a sneeze in the fossil record” as one scientist put it. The rare discovery had features suggesting that Ancestor X was not some squishy eel but more probably looked more like a fish.[4]

6 Unique Fingerprints

Around 1 percent of tracks revealed that dinosaurs had skin on their soles. As skin forms patterns, dinosaur feet could stamp “fingerprints” unique to each individual. However, none of the fossils in question had more than a few traces of skin.

Fingerprint-obsessed scientists thirsted for just one measly fossil fingerprint, and then they got five. Few people have heard of Minisauripus, the smallest theropod. The larger theropods were the type of bipedal carnivores that often chase people in movies. Tyrannosaurus rex is the most famous.

Although Minisauripus is not dramatic enough to hit Hollywood, one of these creatures gave the world footprints unlike any ever seen before. Around 120 million years ago, it left tracks in modern-day Korea.

Discovered in 2019, the exquisitely preserved feet measured 2.5 centimeters (1 in) long. The paws were entirely covered in “fingerprints.” The pattern was surprising. Tiny scales wove together like fabric, producing a pattern that resembled those of Chinese bird fossils. It was something that the team had expected from a much bigger theropod.[5]

5 Ancient Diet And Digestion

When paleontologists want to know what extinct species ate, they have limited options. The shape of teeth and chemical deposits in bones can suggest an animal’s diet. However, to narrow things down, researchers really prefer to find fossilized stomach contents. Unfortunately, soft tissues like the stomach and a digesting meal do not preserve well.

In 1965, a pterosaur fossil (161 to 146 million years old) was unearthed in Southern Germany. The significance of the find was not immediately recognized. In 2015, scientists reviewed the flying reptile at its home museum in Canada. Thankfully, the fossil was in great condition.

Among the well-preserved details were clues about its diet. Inside the guts was something resembling the skeleton of a fish. Best of all was a lump near the base of the pterodactyl’s spine. It was likely a coprolite, or fossilized feces.

Coprolites are rare enough, but finding one inside a pterodactyl would be a first. Analysis of the possible poop revealed what the reptile snacked on. There were spiny remnants suggestive of a marine invertebrate like a sponge or starfish-like prey.[6]

4 Whale Ancestor With Hooves

Whales began as land mammals and evolved until they permanently took to the seas. There are gaps in this story, but in 2011, a crucial piece was recovered. A 42.6-million-year-old whale fossil turned up in Peru. The creature had four legs.

Each foot had a hoof and was webbed like an otter. This odd combination suggested that the animal had walked on land and swum very well. Other whale fossils from this time were too fragmented to suggest how whales went from land to marine mammals.

The flipper-hoofed thing, technically named Peregocetus pacificus, provided a valuable gem. It proved that early whales sometimes lived on land, probably to mate and have young, but could also stay in the water for weeks. It was an extreme semiaquatic lifestyle for a crossover species.[7]

The 4-meter-long (13 ft) animal also provided crucial information about how and when whales spread to the Americas. The Peruvian fossil suggested that they crossed the South Atlantic, which was 50 percent smaller than today, and came from somewhere near India.

3 Cache Of 50-Plus New Species

In 2019, scientists were trudging along China’s Danshui River when they hit the jackpot. The team encountered hundreds of ancient remains, which were duly ogled and discussed.

The fossilized bodies of 101 animals were recovered. Astoundingly, over half were unknown species. Ironically, the researchers sat down to have lunch when they made the discovery.

While eating, somebody noticed telltale signs of ancient mudflows. These are great preservers of fossils, but the Danshui batch blew everyone away. The creatures were so well-preserved that soft tissues and animals that normally did not fossilize appeared to be freshly pressed. There were perfect jellyfish, eyes, gills, digestive systems, soft-bodied worms, and sea anemones, to name but a few.

The cache dated to the Cambrian Period (490 million to 530 million years ago) when animal life diversified at an uncommon pace. The new species present the perfect opportunity to better understand this strangely fruitful time.[8]

2 A New Human

Modern humans are the only survivor of the hominid “family tree.” Cousins like the Neanderthals, Australopithecus, and Homo erectus are long gone. It is not often that a new human species is identified.

But in 2007, a bone turned up in the Philippines. Part of a foot, it was 67,000 years old and the most ancient human fragment in the Philippines. In 2019, 12 more bones were found nearby. Together, they outlined an unknown miniature species of human beings.

This part of the world is already famous for the 2004 discovery of Homo floresiensis, an unrelated tiny hominid nicknamed the “hobbit,” in Indonesia. The newly named Homo luzonensis shared traits with H. sapiens, H. erectus, and Australopithecus.

This mix proved that it was a new species, but a lack of viable DNA obscured evolutionary links with the others. The discovery also contradicted the belief that the first hominins out of Africa were H. erectus, followed by H. sapiens around 40 thousand to 50 thousand years ago.

The small human was outside of Africa almost 10,000 years earlier. Incredibly, their Australopithecus traits are much older. Australopithecus remains have never been found outside Africa, but some specimens are three million years old.[9]

1 The Day The Dinosaurs Died

The K-Pg boundary is a terrible grave marker. Discovered in the 1970s, this layer can be found in rock separating the Cretaceous and Paleogene eras. It is filled with iridium from a massive asteroid that hit near Mexico about 66 million years ago.

The impact left a crater 145 kilometers (90 mi) wide and killed three out of four species, including the dinosaurs. Despite the mass extinction that followed, known as the K-Pg event, no fossils reflected the disaster right after it happened.

In 2019, ancient fish turned up at Hell Creek, North Dakota. They were the first group of large species found at the K-Pg boundary. Even better, the fish had glass spheres in their gills. Caused by the impact, the glass rained down at Hell Creek minutes after the asteroid struck and before the fish were buried in mud, together with animals, plants, and insects.

It was the glass-smothered fish that proved the group had died within a short period from direct consequences of the impact. To view the Hell Creek fossils is to see the day the dinosaurs died.[10]

Read more awesome facts about extinct animals on 10 Awesome Extinct Animals People Don’t Talk About Nearly Enough and Top 10 Animal Endlings: The Last Of Their Kind Before Extinction.