Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

10 Historical British Massacres That Outdo ‘Game Of Thrones’

Game of Thrones is clearly inspired by the jostling of power that has happened in the British Isles for thousands of years—with a few more dragons peppered in. In reality, British history is littered with tales of murder and betrayal that make the Red Wedding look like . . . well, a normal wedding.

Here, we detail 10 of the most fascinating and gruesome historical British massacres that have taken place in the name of conquest or just sheer bloodlust.

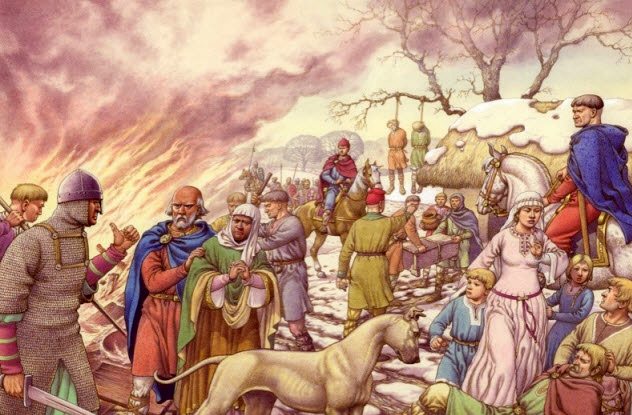

10 The Harrying Of The North

William the Conqueror successfully invaded Britain in 1066 and spent most of the rest of his life attempting to consolidate his power in one way or another. Three years after his initial invasion, his most notorious attempt came in the form of the Harrying of the North.

English rebels in the North had been employing guerrilla tactics—attacking when William’s Norman forces were off guard and then retreating. William found it incredibly hard to engage his enemy or get them to agree to any fixed battle in order for both sides to settle their differences swiftly. Therefore, William decided to fight dirty.

At the end of 1069, he launched a campaign of total annihilation in the North—burning down entire villages and slaughtering the inhabitants. He didn’t stop there. All food supplies in the North of England between the Humber and the River Tees were destroyed to guarantee any survivors would starve to death during the winter. It’s believed that over 100,000 people died.

The massacre was chronicled 50 years later by Benedictine monk Orderic Vitalis:

Never did William commit so much cruelty; to his lasting disgrace, he yielded to his worst impulse and set no bounds to his fury, condemning the innocent and the guilty to a common fate. [ . . . ] I assert, moreover, that such barbarous homicide could not pass unpunished.[1]

9 The Massacre Of Glencoe

In 1692, 15 years before the Act of Union between England and Scotland, James VII was in exile in France as William of Orange looked to consolidate his power within the British Isles.

The clans of Scotland were bound to an oath they had made to James, and as such, William felt the need to clarify his newly acquired authority. He gave them a deadline of January 1, 1692, to declare their allegiance to him or face “the utmost extremity of the law.”[2]

So loyal were the clans that they waited for word from James, still clinging to the idea that he might return and regain power. It took James until December 12, 1691, to admit to himself that it was impossible, and then he released the clans from their oath. It took a further 16 days for the message to reach the Highlands, leaving the clans only a few days to meet William’s deadline.

The MacDonalds of Glencoe struggled to meet the date. Their leader, Alastair MacIain, set off to sign a declaration of loyalty on December 31. Due to the amount of red tape and travel, his signing couldn’t be completed until days after the deadline. This pleased John Dalrymple, Scottish secretary of state, who had a particular dislike for Highlanders. He rejected the late signing and ordered the eradication of the MacDonald clan.

Commander Robert Campbell of Glenylon arrived at Glencoe 12 days before the massacre took place. The soldiers accompanying him had not yet been given their orders. They were friendly with the MacDonalds and requested shelter. The MacDonalds let the soldiers stay in their own houses.

During the night of February 13, Glencoe was caught in a blizzard. While the MacDonalds slept, their guests’ orders were finally laid bare. Thirty-eight were murdered, including MacIain. Of those who managed to escape, 40 more died of exposure in the hills.

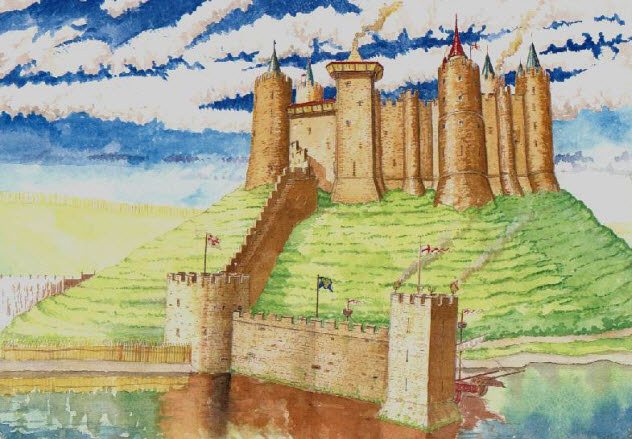

8 The Massacre Of The Jews At York

On March 16, 1190, an estimated 150 Jewish people lost their lives. It was arguably the worst day in the history of York.

There was a strong undercurrent of anti-Semitism throughout Great Britain in the Middle Ages. In this case, the people of York were successfully riled up by four men in particular. They were William Percy, Marmeduke Darell, Philip de Fauconberg, and Richard Malebisse. The men’s motives were born out of financial incompetence and greed.

They had borrowed a large amount from Jewish moneylenders based in York and saw the increasing unrest in the city as an excellent opportunity to wipe their debts clean. Under the cloak of carnage, they were able to access all records of their financial failings and destroy them.[3]

So successfully incensed was the general public that every Jewish person of York became a target and thus was forced to take refuge in the city’s castle. Even there, they were not safe. The crowd remained at fever pitch, unwilling to disperse. Many Jewish people inside the castle’s walls recognized this as an impossible situation and decided to take their own lives rather than eventually face the primal mob.

In the castle’s keep, patriarchs of Jewish families killed their wives and children before setting fire to their surroundings to kill themselves.

7 The Wihtwara Pagan Massacre

In 686, Caedwalla, the king of Wessex, conquered what was then known as Wihtwara and is now known as the Isle of Wight. It’s a strategically useful island off the south coast of England.

The island had changed owners quite a lot. Each time, the occupying power pushed its own beliefs on the existing inhabitants. However, once the dust had settled and the captors had moved onto bigger mainland projects, the people of Wihtwara would routinely revert to good old-fashioned paganism. It was a belief system that was abhorrent to Caedwalla, who professed the importance of Christianity.

To lay lasting claim to Wihtwara and to begin its proper Christianization, King Caedwalla gave every pagan islander a choice. He or she could either sincerely convert to Christianity or be killed. Caedwalla must have doubted many of the islanders’ sincerity because most people are believed to have been killed.[4]

Records are kind of sketchy on what the actual death toll was. Only one survivor is recorded—the king of Wihtwara’s sister, who was married to King Egbert of Kent.

6 The Betrayal Of Clannabuidhe

No entry on this list has acted as a greater inspiration for Game of Thrones and, in particular, the Red Wedding than the Betrayal of Clannabuidhe in 1574.

Sir Brian MacPhelim O’Neill, leader of the O’Neill clan of Clanaboy in what is modern-day Northern Ireland, had been well-liked by the English. He was knighted in 1568 in recognition of his service to the Crown. However, in the six years following his knighting, O’Neill fell progressively out of favor with the English.

The English were suspected of plans to garrison major buildings in Clanaboy, which strongly contributed to the dissolution of the alliance and O’Neill’s preemptive destruction of those structures to make the plans impossible.[5]

It was in the name of peace that he invited the earl of Sussex to a feast at his castle at Castlereagh, and indeed, everything was amicable until the feast’s end. At that point, O’Neill and his close family were seized as English forces slaughtered between 200 and 500 unarmed, unsuspecting guests. O’Neill, his wife, and his brother were then taken to Dublin Castle, where they were hanged, drawn, and quartered.

5 St. Brice’s Day Massacre

St. Brice’s Day occurs on November 13 and has become synonymous with the massacre that took place on it in 1002.

Fed up with persistent Danish raids in the preceding years by Danish King Sweyn I, the English King AEthelred the Unready decided to take extreme measures. Fearing further Danish attacks and to prevent an uprising, AEthelred decided to kill every Dane already living within his territory.

The exact number of deaths is unknown, but it’s believed that many people died. Most likely, the campaign of extermination only took place in areas of England that were not in the Danelaw. Naturally, those places were protected by Danish law and had been for over 100 years. Any attempts at slaughter in the Danelaw would have been met with significant resistance.

We do specifically know that there were a lot of deaths in Oxford. AEthelred wrote of an incident at a local church:

All the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockle among the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination . . . those Danes who dwelt in [Oxford], striving to escape death, entered this sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and bolts, and resolved to make refuge . . . but when all the people in pursuit strove, forced by necessity, to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to the planks and burned, as it seems, this church.[6]

In 2008, during an excavation at St. John’s College, Oxford, the charred remains of at least 35 men were found. Further tests found that they were Vikings.

4 The Storming Of Bolton

The Storming of Bolton (aka the Bolton Massacre) most likely resulted in the greatest loss of life of any massacre during the nine-year English Civil War. It occurred on May 28, 1644, when the Roundhead (Parliamentarian) town of Bolton was attacked in the night by the Cavaliers (Royalists), under the command of Prince Rupert.

His army consisted of 2,000 cavalry and 6,000 infantry. In the dark during a heavy rainstorm, Rupert’s forces adopted a slice-first-ask-questions-later policy that resulted in the deaths of around 1,600 people. This included civilians as well as off-guard soldiers.

As is often the case, the numbers are disputable. The death estimate comes from Roundhead sources. It could have propagandistic roots, with the Roundheads inflating the number of unarmed casualties to heighten perceptions of Cavalier barbarism. Only 78 Boltonians’ deaths are noted in the town’s parish register.[7]

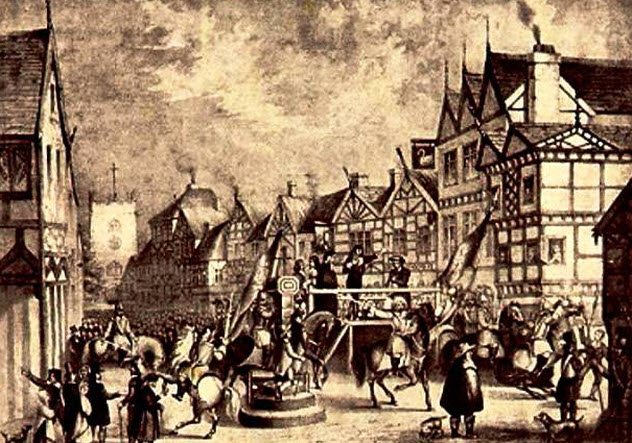

3 The Peterloo Massacre

In the years leading up to the Peterloo Massacre on August 16, 1819, there had been a tremendous amount of unrest in the entire Lancashire area. The textile industry was largely concentrated in the northern areas of England and was badly affected by a national economic depression.

Factory owners had cut the wages of their workers by as much as two-thirds. Also, the Corn Laws had been introduced in 1815, which enforced tariffs on grain. When these measures were combined with pay cuts, factory workers could no longer afford food. This affected around one million working-class people in the Lancashire area, yet they were represented by only two Members of Parliament.[8]

Politicians such as Henry Hunt became incredibly popular with the working class during this period by championing parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws. The massing of 60,000–80,000 people on August 16, 1819, was centered on hearing Hunt and others speak about such issues as well as sending a message that change was needed to the greater powers that be.

It’s been documented that the gathering was fairly calm. People brought their entire families and had picnics during the day. However, when Henry Hunt began to give his speech, the chairman of the local magistrates ordered his cavalry to arrest Hunt.

The cavalry was separated from Hunt by the crowd and decided to simply use their sabers to hack away all who stood in their way. It took 10 minutes for the crowd to flee, and 11–18 people suffered injuries that resulted in death. The number of nonfatal injuries has been estimated to be as high as 700.

As a direct result of this incident, a newspaper called the Manchester Observer was formed to report the truth about the Peterloo Massacre. Two years later, this morphed into The Manchester Guardian, which is now simply known as The Guardian.

2 The Massacre Of Berwick

When Margaret, Maid of Norway and recognized Queen of Scots, died in 1290, no clear heir was apparent. As a result, many people claimed that the throne was rightfully theirs. This prolonged period of uncertainty meant that the Guardians of Scotland, then serving as de facto heads of state, asked King Edward I to help arbitrate the dispute. Ultimately, he chose John Balliol to become the king of Scotland.

Edward thus expected a level of loyalty from Balliol that was not received. Edward ordered Scotland to send troops to help fight in England’s war against France. Not only did Balliol refuse, but in direct response, he formed the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France in 1295.

King Edward retaliated by sacking the economic stronghold of Berwick, which lies on the border between Scotland and England. The greatest atrocities happened in the days after the sacking, as documented in the 15th-century chronicle The Scotichronicon.

It states, “When the town had been taken . . . Edward spared no one, whatever the age or sex, and for two days, streams of blood flowed from the bodies of the slain, for in his tyrannous rage, he ordered 7,500 souls of both sexes to be massacred.”[9]

Edward’s troops continued marching north through Scotland, decisively winning the Battle of Dunbar and forcing John Balliol to abdicate soon after.

1 The Menai Massacre

The Menai Massacre took place during the Roman conquest of Anglesey in either AD 60 or 61. Anglesey is the largest island in Wales and was the home of many druids, the spiritual leaders of the native people.

It also was a place of refuge for many tribesmen who fled Roman rule. Thus, the Romans came to see Anglesey as a particularly troublesome place and the site of a possible uprising. As such, the decision was made to massacre the island’s inhabitants.

By the time that Roman General Suetonius Paulinus and his legions reached the Menai Straits, the inhabitants of Anglesey realized that there was no escape. Roman historian Tacitus detailed what happened next:

On the shore stood a dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women . . . with hair disheveled, waving brands. All around, the druids, urged by their hands to Heaven and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight. [ . . . ] Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onward, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the fore in the flames of his own brands.[10]

The actual number of casualties is unknown. All traces of the druids were obliterated. However, it is clear that not everyone on the island was killed as the Romans established a garrison in Anglesey in which the native tribes were indentured.

David is a freelance writer and Creative Writing MA student. You can read more of his articles at CultureRoast.com. Follow him on Twitter and Like him on Facebook.

Read about more horrifying massacres on 10 Lesser Known Massacres and 10 More Little Known Massacres.

![10 Worst Massacres Of African-Americans [DISTURBING IMAGES] 10 Worst Massacres Of African-Americans [DISTURBING IMAGES]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/vote-150x150.jpg)